[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Early Years in Yosemite >

[California Historical Society Quarterly 5(4):328-341 (December 1926)]

As early as 1806 a party of Spaniards explored the lower course of the Merced River, but, it is doubtful if they ascended far above the Indian villages in the foothills. The first authentic information that we have of exploration in the Yosemite region is given us by Zenas Leonard, clerk of the now well-known Walker expedition. So much has recently been published on Joseph Reddeford Walker that it is only necessary to remind the reader that in 1833 he followed a course that took him directly through what is now Yosemite National Park. Judging from Leonard’s reference to “mile high precipices” and streams that “precipitated themselves from one lofty precipice to another,” we may well suppose that this party was the first to look into Yosemite Valley or Hetch Hetchy or both. Their views were all from the “rim” above and it is certain that no descent was made by them to the Valley floor. [Editor’s note: today historians generally believe the Walker party looked down The Cascades, which are just west of Yosemite Valley, instead of Yosemite Valley itself.—dea]

No other written accounts are known of which any parts may be construed as referring to Yosemite until the appearance of Judge Marvin’s account published in the Alta California, April 23, 1851. Marvin was quartermaster of the Mariposa Battalion but did not enter Yosemite with the organization when the first expedition was made.

After the rush of gold seekers to the first scenes of mining activity in 1849, there came a natural extension of mining both north and south. In the winter of 1850 miners were busy in the mountains just west of Yosemite, and it was during that winter that B. F. Johnson, better known as “Quartz Johnson,” discovered the Johnson Lode later famous through its connection with Colonel Frémont.1 The foothills swarmed with excited miners; the towns of Mariposa, Bear Valley, Mount Bullion and Coulterville sprang up in the vicinity of the discoveries; and adventurous traders established trading posts outside of towns to accommodate the miners and the Indians.

One such trader was James D. Savage, who maintained a store at the mouth of the South Fork of the Merced. Unfriendly Indians drove him from this location in the spring of 1850 and he removed his store and mining camp to Mariposa Creek. He found it possible to exchange his goods for gold at an enormous profit and extended his thriving business by establishing a second trading post on the Fresno River. He took to himself five Indian wives and apparently won the confidence and good will of the tribes with which he was associated. But the

[click to enlarge] |

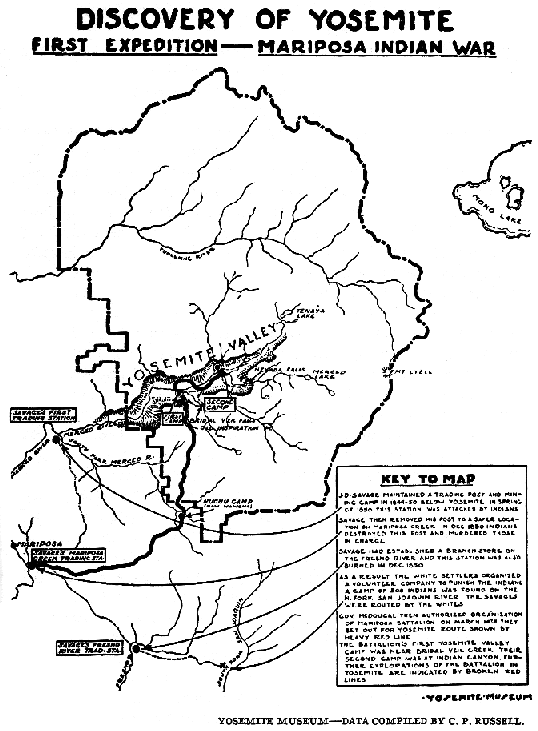

When it was rumored that the Indians were concentrating for a more extensive operation, it was not difficult to bring the white settlers to an agreement to organize for self-protection. Without official authority a party under the leadership of Sheriff Burney and James D. Savage started at once to check the marauders who were assembling in the foothills. Several skirmishes were had with the Indians, the most important at a large Indian camp on the North Fork of the San Joaquin. By this time, Governor McDougal had been appealed to and by his authority two hundred militiamen were called out. Savage was elected major of the new battalion, and three companies, under John J. Kuykendall, John Boling, and William Dill, were organized and drilled near Savage’s Mariposa camp. The movements of this organization have recently been so thoroughly described by R. S. Kuykendall2 that I will not dwell at length on their discovery of Yosemite. Suffice it to say that in March, 1851, they set out for the mountain stronghold of the troublesome Indians, following a route very near that which is now known as the Wawona Road to Yosemite Valley.

On the South Fork of the Merced at what we call Wawona, a Nuchu camp was surprised and captured. Messengers sent ahead from this camp returned with the assurance that the Yosemite tribe would come in and give themselves up. Old Chief Tenaya of the Yosemites did come into camp, but, after waiting three days for the others, Major Savage became impatient and set out with the battalion to enter the much talked-of Yosemite retreat. When they had covered about half the distance to the Valley, seventy-two Indians were met plodding through the snow. Not convinced that this band constituted the entire tribe, Savage sent them to his camp on the South Fork while he pushed on to the Valley.

On March 25, 1851, the party went into camp near Bridal Veil Fall. That night around the camp fire a suitable name for the remarkable valley was discussed. Lafayette H. Bunnell, a young man upon whom the surroundings and events had made a deeper impression than upon any of the others, urged that it be named Yosemite, after the natives who had been driven out. This name was agreed upon. Although the whites knew the name of the tribe, they were apparently unaware that the Indians had another name, Ahwahnee, for the Valley.

The next morning the camp was moved to the mouth of Indian Canyon, and the day was spent in exploring the Valley. Only one Indian was found, an ancient squaw, too feeble to escape. Parties penetrated Tenaya Canyon above Mirror Lake, ascended the Merced Canyon beyond Nevada Fall, and explored both to the north and to the south of the river on the Valley floor. No more Indians were discovered, and on the third day the party withdrew from the Valley. The Indians who had been gathered while the party was on the way to the Valley escaped from their guard while en route to the Indian Commissioner’s camp on the Fresno; so this first expedition accomplished nothing in the way of subduing the Yosemites.

The Indian Commissioners then in California made a concerted effort to treat with all existing tribes. In May, 1851, Major Savage sent Captain John Boling and his company back to Yosemite to surprise the elusive inhabitants and to whip them well. Boling followed the same route taken previously and arrived in Yosemite on May 9. He made his first camp near the site of the present Sentinel Hotel. Chief Tenaya and a few of his followers were captured, but the majority of the Yosemites eluded their pursuers. It was during this stay in Yosemite that the first letter from the Valley was dispatched. On May 15, 1851, Captain Boling wrote to Major Savage of his affairs, and the letter was published in the Alta California, June 12, 1851.

On May 21, some members of the invading party discovered the fresh trail of a small party of Indians traveling in the direction of the Mono country. Immediate pursuit was made, and on the 22nd the Yosemites were discovered encamped on the shores of Tenaya Lake in a spot much of which was snow covered. They were completely surprised and surrendered without a struggle. This was the first expedition made into the Yosemite high country from the west, and it was on this occasion that the name Lake Tenaya was applied by Bunnell. The old Indian chief, on being told of how his name was to be perpetuated, sullenly remonstrated that the lake already had a name, “Py-we-ack” — Lake of the Shining Rocks.3

In the early spring of 1926 I made a trip through the snow to Tenaya Lake, and as I skiied over the soft surface, I tried to imagine the amusing spectacle of Captain Boling’s men “stripped to the drawers, in which situation all hands ran at full speed at least four miles, some portion of the time over and through snow ten feet deep.”4

The Indians were on this second occasion successfully escorted to the Fresno reservation. Tenaya and his band, however, refused to adapt themselves to the conditions under which they were forced to live. They begged repeatedly to be permitted to return to the mountains and to the acorn food of their ancestors. At last, on his solemn promise to behave, Tenaya was permitted to go back to Yosemite with members of his family. In a short time his old followers quietly slipped away from the reservation and joined him. No attempt was made to bring them back.

During the winter of 1851-1852, no complaints against the Yosemites were registered, but in May of 1852 a party of eight prospectors made their way into the Valley where two of them were killed by the Indians.

Recently a remarkable manuscript prepared by a member of this party has come into my hands. Apparently the article was obtained by Mrs. A. E. Chandler of Santa Cruz, who in 1901 mailed it to Galen Clark in Yosemite. It remained in Galen Clark’s possession until his death, when it, together with other papers, was turned over to the pioneer Yosemite photographer, George Fiske. When Mr. Fiske died, the papers were given to National Park Service officials, and have but just now been placed in the Yosemite Museum for use and safe keeping.

These reminiscences of Stephen F. Grover’s are apparently so authentically presented and divulge so much that has been unrecorded that I welcome the opportunity to publish them. Readers who are familiar with Yosemite history as it has been accepted since the appearance of Bunnell’s Discovery of Yosemite in 1880 will recognize a number of incidents that are at variance with previous records.

[Grover’s Narrative]

A Reminiscence

On the 27th of April, 1852, a party of miners, consisting of Messrs. Grover. Babcock, Peabody, Tudor, Sherburn, Rose, Aich, and an Englishman whose name I cannot now recall, left Coarse Gold Gulch in Mariposa County, on an expedition prospecting for gold in the wilds of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. We followed up Coarse Gold Gulch into the Sierras, traveling five days, and took the Indian trail through the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, and were the first white me: to enter there. Then we followed the South Fork of the Merced River, travelin: on Indian trails the entire time.

On reaching the hills above Yosemite Valley, our party camped for the night and questioned the expediency of descending into the Valley at all. Our parry were all opposed to the project except Sherburn, Tudor, and Rose. They over-persuaded the rest and fairly forced us against our will, and we finally follow,: the old Mariposa Indian trail on the morning of the 2nd of May, and entering the Valley on the East side of the Merced River, camped on a little opening, neat bend in the River free from any brush whatever, and staked out our pack mules by the river. I, being the youngest of the party, a mere boy of twenty-two years, and not feeling usually well that morning, remained in camp with Aich and the Englishman to prepare dinner, while the others went up the Valley, some prospecting, and others hunting for game. We had no fear of the Indians, as they had been peaceable, and no outbreaks having occurred, the whites traveled fearlessly wherever they wished to go. Thus, we had no apprehension of trouble. To my astonishment and horror I heard our men attacked, and amid firing, screams, and confusion, here came Peabody, who reached camp first, wounded by an arrow in his arm and another in the back of his neck, and one through his clothes, just grazing the skin of his stomach, wetting his rifle and ammunition in crossing the river as he ran to reach camp. Babcock soon followed, and as both men had plunged through the stream that flows from the Bridal Veil Falls in making their escape, they were drenched to the skin.

On reaching us, Aich immediately began picking the wet powder from Babcock’s rifle, while I with my rifle stood guard and kept the savages at bay the best I could. (The other men, with the exception of Sherburn, Tudor and Rose, came rushing into camp in wild excitement.) Rose, a Frenchman, was the first to fall, and from the opposite side of the stream where he fell, apparently with his death wound, he screamed to us “Tis no use to try to save ourselves, we have all got to die.” He was the only one of our company that could speak Indian and we depended on him for an interpreter. Sherburn and Tudor were killed in this first encounter, Tudor being killed with an ax in the hands of a savage, which was taken along with the party for cutting wood. The Indians gathered around as near as they dared to come, whooping and yelling, and constantly firing arrows at us. We feared they would pick up the rifles dropped by our companions in their flight, and turn them against us, but they did not know how to use them. As we were very hard pressed, and as the number of Indians steadily increased, we tried to escape by the old Mariposa trail, the one by which we entered the Valley, one of our number catching up a sack of a few pounds of flour and another a tin cup and some of our outer clothing and fled as best we could with the savages in hot pursuit. We had proceeded but a short distance when we were attacked in front by the savages who had cut off our retreat. Death staring at us on almost every hand, and seeing no means of escape, we fled to the bluff, I losing my pistol as I ran. We were in a shower of arrows all the while, and the Indians were closing in upon us very fast; the valley seemed alive with them — on rocks, and behind trees, bristling like Demons, shrieking their war whoops, and exulting in our apparently easy capture. We fired back at them to keep them off while we tried to make our way forward hugging the bluff as closely as possible. Our way was soon blocked by the Indians who headed us off with a shower of arrows, (two going through my clothing, one through my hat which I lost), when from above the rocks began to fall on us and in our despair we clung to the face of the bluff, and scrambling up we found a little place in the turn of the wall, a shelf-like projection, where, after infinite labor, we succeeded in gathering ourselves, secure from the falling rocks, at least, which were being thrown by Indians under the orders from their Chief. The arrows still whistled among us thick and fast, and I fully believe — could I visit that spot even now after the lapse of all these years — I could still pick up some of those flint arrow points in the shelf of the rock and in the face of the bluff where we were huddled together.

We could see the old Chief Tenieya way up in the Valley in an open space with fully one hundred and fifty Indians around him, to whom he gave his orders which were passed to another Chief just below us, and these two directed those around them and shouted orders to those on the top of the bluff who were rolling the rocks over on us. Fully believing ourselves doomed men, we never relaxed our vigilance, but with the two rifles we still kept them at bay, determined to sell our lives as dearly as possible. I recall, with wonder, how every, event of my life up to that time passed through my mind, incident after incident, with lightning rapidity, and with wonderful precision.

We were crowded together beneath this little projecting rock, (two rifles were fortunately retained in our little party, one in the hands of Aich and one in my own), every nerve strung to its highest tension, and being wounded myself with an arrow through my sleeve that cut my arm and another through my hat, when all of a sudden the Chief just below us, about fifty yards distant, suddenly threw up his hands and with a terrible yell fell over backwards with a bullet through his body. Immediately, the firing of arrows ceased and the savages were thrown into confusion, while notes of alarm were sounded and answered far up the Valley and from the high bluffs above us. They began to withdraw and we could hear the twigs crackle as they crept away.

It was now getting dusk and we had been since early morning without food or rest. Not knowing what to expect we remained where we were, suffering from our wounds and tortured with fear till the moon went down about midnight; then trembling in every limb, we ventured to creep forth, not daring to attempt the old trail again; we crept along and around the course of the bluff and worked our way up through the snow, from point to point, often feeling the utter impossibility of climbing farther, but with an energy born of despair, we would try again, helping the wounded more helpless than ourselves, and by daylight we reached the top of the bluff. A wonderful hope of escape animated us though surrounded as we were, and we could but realize how small our chances were for evading the savages who were sure to be sent on our trail. Having had nothing to eat since the morning before, we breakfasted by stirring some of our flour in the tin cup, with snow, and passing it around among us, in full sight of the smoke of the Indian camps and signal fires all over the valley.

Our feelings toward the “Noble Red Man” at this time can better be imagined than described.

Starting out warily and carefully, expecting at every step to feel the stings of the whizzing arrows of our deadly foes, we kept near and in the most dense underbrush, creeping slowly and painfully along as best we could, those who were best able carrying the extra garments of the wounded and helping them along; fully realizing the probability of the arrow tips with which we were wounded having been dipped in poison before being sent on their message of death. In this manner we toiled on, a suffering and saddened band of once hopeful prospectors.

Suddenly a deer bounded in sight. Some objected to our shooting as the report of our rifle might betray us — but said I, “As well die by our foes as by starvation,” and dropping on one knee with never a steadier nerve or truer aim, the first crack of my rifle brought him down. Hope revived in our hearts, and quickly skinning our prize we roasted pieces of venison on long sticks thrust in the flame and smoke, and with no seasoning whatever it was the sweetest morsel I ever tasted. Hastily stripping the flesh from the hind quarters of the deer, Aich and myself, being the only ones able to carry the extra burden, shouldered the meat and we again took up our line of travel. In this manner we toiled on and crossed the Mariposa Trail, and passed down the south fork of the Merced River, constantly fearing pursuit. As night came on we prepared camp by cutting crotched stakes which we drove in the ground and putting a pole across enclosed it with brush, making a pretty secure hiding place for the night, where we crept under and lay close together. Although expecting an attack we were so exhausted and tired that we soon slept.

An incident of the night occurs to me: — One of the men on reaching, out his foot quickly, struck one of the poles, and down came the whole structure upon us. Thinking that our foes were upon us, our frightened crowd sprang out and made for the more dense brush, but as quiet followed we realized our mistake and gathering together again we passed the remainder of the night in sleepless apprehension. When morning came we started again, following up the river, and passed one of our camping places. We traveled as far as we could in that direction, and prepared for our next night to camp and slept in a big hollow tree, still fearing pursuit. We passed the night undisturbed and in the morning started again on our journey, keeping in the shelter of the brush, and crossed the foot of the Falls, a little above Crane Flat—so named by us, as one of our party shot a large crane there while going over, but it is now known as Wawona. We still traveled in the back ground, passing through Big Tree Grove again, but not until we gained the ridge above Chowchilla did we feel any surety of ever seeing our friends again.

Traveling on thus for five days, we at last reached Coarse Gold Gulch once more, barefooted and ragged but more glad than I can express. An excited crowd soon gathered around us and while listening to our hair-breadth escapes, our sufferings and perils, and while vowing vengeance on the treacherous savages, an Indian was seen quickly coming down the mountain trail, gaily dressed in war paint and feathers, evidently a spy on our track, and not three hours behind us. A party of miners watched him as he passed by the settlement. E. Whitney Grover, my brother, and a German cautiously followed him. The haughty Red Man was made to bite the dust before many minutes had passed.

My brother Whitney Grover quickly formed a company of twenty-five men, who were piloted by Aich, and started for the Valley to bury our unfortunate companions. They found only Sherburn and Tudor, after a five days march, and met with no hostility from the Indians. They buried them where they lay, with such land marks as were at hand at that time. I have often called to mind the fact that the two men, Sherburn and Tudor, the only ones of our party who were killed on that eventful morning, were seen reading their Bibles while in camp the morning before starting into the Valley. They were both good men and we mourned their loss sincerely.

After we had been home six days, Rose, who was a partner of Sherburn and Tudor in a mine about five miles west of Coarse Gold Gulch, where there was a small mining camp, appeared in the neighborhood and reported the attack and said the whole party was killed, and that he alone escaped. On being questioned he said he hid behind the Waterfall and lived by chewing the leather strap which held his rifle across his shoulders. This sounded strange to us as he had his rifle and plenty of ammunition and game was abundant. Afterward hearing of our return to Coarse Gold Gulch camp, he never came to see us as would have been natural, but shortly disappeared. We thought his actions and words very strange and we remembered how he urged us to enter the Valley, and at the time of the attack was the first one to fall, right amongst the savages, apparently with his death wound, and now he appears without a scratch, telling his version of the affair and disappearing without seeing any of us. We all believed he was not the honest man and friend we took him to be. He took possession of the gold mine in which he held a one-third interest with Sherburn and Tudor, and sold it.

Years afterward, in traveling at a distance and amongst strangers, I heard this story of our adventures repeated, as told by Aich, and he represented himself as the only man of the party who was not in the least frightened. I told them that “I was most thoroughly frightened, and Aich looked just as I felt.”

Stephen F. Grover, Santa Cruz, California.

The commander of the regular army garrison at Fort Miller was notified of these events and a detachment of the Second Infantry under Lieutenant Tredwell Moore was dispatched in June, 1852. Five Indians were captured in the Yosemite Valley, all of whom were found to possess articles of clothing belonging to the murdered men. These Indians were summarily shot. Tenaya’s scouts undoubtedly witnessed this prompt pronouncement of judgment, and the members of the tribe fled with all speed to their Piute allies at Mono Lake.

The soldiers pursued the fleeing Indians by way of Tenaya Lake and Bloody Canyon. They found no trace of the Yosemites and could elicit no information from the Piutes. The party explored the region north and south of Bloody Canyon and found some promising mineral deposits. In August they returned to Tuolumne Soda Springs and then made their way back to Mariposa by way of the old Mono Trail that passed south of Yosemite Valley.

Upon arrival at Mariposa they exhibited samples of their ore discoveries. This created the usual “excitement,” and Lee Vining with a party of companions hastened to visit the region to prospect for gold. Leevining Canyon, through which the Tioga Road now passes, was named for the leader of this party. By 1857 word reached miners west of the range that rich deposits had been found at the Mono Diggings, and a rush from the Tuolumne mines resulted. In 1859 the great wealth of Bodie was discovered, and the Mono mining excitement was on in earnest.

Tenaya and his refugee band remained with the Mono Indians until late in the summer of 1853 when they again ventured into their old haunts in the Yosemite Valley. Shortly after they had re-established themselves in their old home, a party of young Yosemites made a raid on the camp of their former hosts and stole a band of horses which the Monos had recently driven up from southern California. The thieves brought the animals to Yosemite by a very roundabout route through a pass at the head of the San Joaquin, hoping by this means to escape detection. However, the Monos at once discovered the ruse, and organized a war party to wreak vengeance upon their ungrateful guests. Surprising the Yosemites while they were feasting gluttonously upon the stolen horses, they almost annihilated Tenaya’s band with stones before a rally could be effected. Eight of the Yosemite braves escaped the slaughter and fled down the Merced Canyon. The old men and women who escaped death were given their liberty, but the young women and children were made captive and taken to Mono Lake. The story of this last act in the elimination of the troublesome Yosemites was made known to Bunnell by surviving members of the tribe. A number of parties of miners emboldened by the news, visited the Valley in the fall of 1853. During 1854 no white men are known to have entered the Valley.

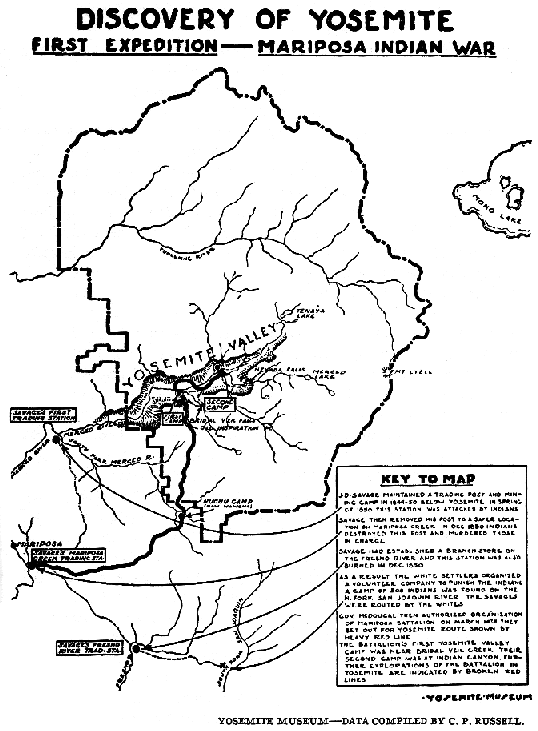

By 1855 several accounts written by members of the three punitive expeditions that had entered Yosemite had been published in San Francisco papers. The difficulties of overcoming hostile Indians in the search for gold were far more prominent in the minds of these writers than the scenic wonders of the new-found valley. Nevertheless, the mention of a thousand-foot waterfall in one of these published letters awakened James M. Hutchings, then publishing the California Magazine, to the possibilities that Yosemite presented. Hutchings organized the first tourist party in June, 1855, and with two of the original Yosemites as guides proceeded from Mariposa over the old Indian trail to the Valley.5 Thomas Ayres, an artist, was a member of the party and during this visit he made the first sketches ever made in Yosemite.

[click to enlarge] THE FIRST PICTURE MADE IN YOSEMITE By THOMAS A. AYRES, 1855 |

Several other parties followed that year. Milton and Houston Mann, who had accompanied one of these sight-seeing expeditions, were so imbued with the possibilities of serving the hordes of visitors soon to come that they set to work immediately to construct a horse toll-trail from the South Fork of the Merced to the Yosemite Valley. Galen Clark, who had also been a member of one of these 1855 expeditions, was prompted to establish a camp on the South Fork where travelers could be accommodated. This camp was located at the beginning of the Mann Brothers’ trail and later became known as Clark’s Station. We call it Wawona now. The Mann brothers finished their trail in 1856. In the same year George W. Coulter, assisted by Bunnell, built the “Coulterville Free Trail” from Bull Creek through Hazel Green and Tamarack Flat to the Valley.

The first habitation to be constructed by white men in Yosemite was a rough shack put up in 1855 by a party of surveyors of which Bunnell was a member. A company had been organized to bring water from the foot of the Valley into the “dry diggings” of the Mariposa estate. It was supposed that a claim in the Valley would doubly secure the water privileges.7

The first permanent structure was built in 1856 by Walworth and Hite. It was known as the “Lower Hotel” and occupied the site later occupied by Black’s Hotel.8

In the spring of 1857, Beardsley and Hite put up a canvas covered house on the site of the present “Cedar Cottage.” The next year this was replaced by a wooden structure, the planks for which had been whipsawed by hand. In 1859 C. L. Weed took the first photograph in Yosemite, with this building as his first subject. [Editor’s note: Charles Leander Weed’s first photograph, taken June 18, 1859 was of Yosemite Falls, not Hite’s Hotel, which was photographed 3 days later—dea.] This ancient hotel still stands and is known as “Cedar Cottage.” It was to this hostelry that J. M. Hutchings came in 1864 in the role of proprietor. The mirth and discomfiture engendered among Hutchings’ guests by the cheese cloth partitions between bedrooms prompted him to build a sawmill near the foot of Yosemite Falls in order to produce sufficient lumber to “hard finish” his hostelry. It was in this mill that John Muir found employment for a time. The hotel was embellished with lean-tos and porches and an addition was constructed at the rear in which was completely enclosed the trunk of a large growing cedar tree. Hutchings built a great fireplace in this sitting room and proceeded to make the novel gathering place famous as the “Big Tree Room.”9

A winter spent in the frigid shade of the south wall of Yosemite Valley convinced the Hutchings family that their “Big Tree Room” was not a pleasant winter habitation. Like the inhabitants of the latest Yosemite village they built anew and moved into the warm sunshine of the north side of the Valley. With their own hands members of the family constructed a snug cabin among giant black oaks near the foot of Yosemite Falls and there spent the remainder of their Yosemite days.

One of the mountaineers who aided in the construction of the “Upper Hotel” or “Hutchings House” in 1859 was James C. Lamon. That same year he located a preemption claim at the upper end of the Valley, built the first log cabin, and planted a fine orchard. This orchard still flourishes and marks the site of the activities of this first permanent settler in Yosemite. For fifteen years Lamon endeared himself to his Yosemite neighbors. Following his death, in 1875, his premises were occupied by A. Harris, who established the first public camp ground in Yosemite.

In 1864 a bill introduced by Senator Conness of California was passed by Congress granting Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove to the State of California as a public trust. Governor Low of California then proclaimed eight citizens known to be familiar with the region as a board of commissioners to manage the Valley. They in turn, appointed Galen Clark as guardian. In 1866 the State legislature enacted a law providing for the administration of the grant and made a small appropriation for the first two years. From that time the inhabitants of the Yosemite Grant found themselves subject to regulation by the commissioners.

When in 1869, George F. Leidig was ejected from the “Lower Hotel” by A. G. Black, from whom he had leased the property, he secured permission from the commissioners to build a hotel of his own. Leidig’s Hotel was located near the foot of the present Glacier Point Short Trail, about four hundred yards below the rival “Lower Hotel.” If we may judge from the notes of contemporary writers, Mrs. Leidig excelled all others in her kitchen management. Mr. and Mrs. Black, who undertook the operation of the “Lower Hotel” in 1869 initiated their regime by removing the old hotel and constructing on its site a new one known as “Black’s Hotel.” Both Black’s and “Leidig’s” were torn down by order of the Commissioners in 1888.

Of the many comments on hosts and hostelries that one may find in the score of books written on Yosemite during the ’70’s none commands such voluminous and favorable notice as do J. C. Smith and his famous “Cosmopolitan” bath house and saloon. This favorite resort was built in 1870 and has served continuously to the present time. The building is now occupied by the general offices of the hotel and transportation company.

Another pioneer in Yosemite’s hotel business was Albert Snow, proprietor of “La Casa Nevada.” In 1869-70 Snow built a trail up the canyon of the Merced and constructed a resort on the flat between Vernal and Nevada Falls. The register of this unique hotel is now among the most prized possessions of the Yosemite Museum. Fire eventually destroyed “La Casa Nevada,” and only the ruined foundations and a pile of broken bottles mark its site.

Glacier Point was from the earliest days recognized as a most desirable vantage point, yet from the Valley it was at first accessible only to those nimble tourists capable of scrambling up the ledge and through the steep chimney below the point. In 1871 there came to Yosemite one who was destined to do much toward making accessible points on the Valley’s rim. This man was John Conway, and several of the most used trails in the park serve as monuments to his energy and ability. His first task was to build the trail from Snow’s to Little Yosemite. That finished, he undertook the same year the construction of the “Four Mile Trail” to Glacier Point. This work was done for McCauley, who later took over Peregoy’s Glacier Point stopping place and built the Glacier Point Mountain House. The “Four Mile Trail” was completed in 1872. In 1873 Conway built the Eagle Peak Trail and operated it as a toll trail until it was purchased by the State.

Among the Galen Clark papers recently acquired by the Yosemite Museum is a letter from John Conway outlining his work of trail building in the Yosemite. The letter constitutes an interesting record and is reproduced here, just as written.

Fort Monroe Camp, Wawona & Yosemite Road, July 12, 1891.

Galen Clark, Guardian Yosemite Park

Friend Clark

Yours of the 21st ult. at hand—In reply — The first of my work Engineering and Construction of Roads & trails in Yosemite was commenced July 1st. 1871. beginning at the Stair [Little Yosemite & Clouds Rest Trail]. The Chiefs of Civil Engineering had pronounced Yo Semite unapproachable by wagon or stage road. For that reason horseback trails are first in the history of that class of improvements.

Capt. Jarvis Kiel (My instructor) had preceeded me to do the Engineering — The transit was set at the top of the wall, telescope depressed cutting the talas at highest point down the canyon indicating too high an angle for this purpose (direct line) and cutting high on the Solid Granite base of Liberty Cap. For three days we walked, stood, sat, and gazed into that solid granite corner. On the evening of the third day the Captin borrowed the instrument saying, “John you see through the telescope all I can tell how to proceed in this matter.” “You have come here to build I know you have a way of your own that others know nothing of, to work out difficult problems. I place the Engineering in your own hands, draw plan in your own judgement.” Seated at the top of the wall opposite the stair with a cane for instrument of triangulation (used as straight edge) I drew the plan for as it stand tody. Kiel staked the line from Little Yo Semite to Glacier Point. Sent a force of men jimmy O Hare foreman to cut it through during the time of constructing the Stair, it being the sticking point. everybody saying it couldent be done.

A temporary trail was first constructed for passing saddle train stock to graze in Little Yo Semite. The moment the mule could climb through the Tourist insisted upon riding him through. to tell them it was dangerous was useless—go through they did, which added to the difficulty of carrying on the work, all material haveing to be brought from the top down.

The Glacier Point Trail was next. I commenced the Engineering and Construction late in the season of 1871 it was completed the following summer [1872] Built the Stage Road down the vally [north side] from Hutchings, also made preliminary Surveys for Stage road on both sides the Vally From Gentrys on the north and Clarks on the south estimating cost of construction. Examined the wall and fixed upon route of Eagle Peak Trail. The same year [1872] broke ground commencing construction of Eagle Peak Trail May 7th 1873 reaching the foot of upper Yo Semite falls that season — and succeeded in its completion to Eagle Peak in Nov. 1877. Early in 1874 made the road up the vally from Hutchings [south side] for a wood road. Made the present road from Hutching down to Blacks during the flood of 1876. Was called in consultation to select sites for two iron bridges. Made measurements and estimates for cost of butments and built them assisting at the erection of the bridges. Commenced the assent of Sout Dome in August 1871. Had examined the rock in ’69, had observed seams in the rock. Made eye bolts wedge point, to drive in without drilling, my time being limited to one day on the assent had not provided drills and hammer. Failing to reach the top I left the material at the base Anderson carried out the plan useing my material,—I have no record of the cost of the Eagle Peak Trail. The account of first part was burned in my camp on the Oak Flat Road at the time of its construction. And records of 2nd division were lost in the flood of 1878. It was built out of the earnings of my family and self — dureing the interval of its construction. The cash expended—outside my own time and labor was perhaps fifteen hundred to two thousand dollars. I transferd the property to the State in 1883—recieving Controllers warrent for fifteen hundred dollars in exchange.

In conclusion I wish to state that in all the work I have done in Yo Semite the most rigid economy was used—“want of fund” was the ever shadowing gost from begining to end—otherwise the grades—and execution of the construction would of been better—

Respectfully, Your humble Servt

John Conway.

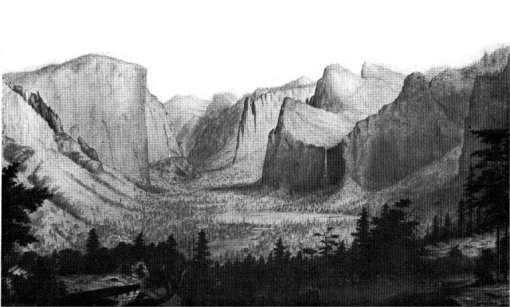

[click to enlarge] MARIPOSA ROAD OPENING 1875 A pioneer celebration at Coulter and Murphy’s (Cedar Cottage) that contrasts interestingly with the great festivities incident to opening of the Yosemite water grade highway in 1926. YOSEMITE MUSEUM—GIFT OF T. W. WARD. |

By 1873, 12,000 tourists had ridden into the Valley via Mariposa, Coulterville, or Big Oak Flat. Provisions, supplies, John Smith’s bath tubs and billiard tables, had all been packed in on the backs of mules. Roads were approaching closer and closer to the Yosemite Grant, and in 1874 both the Coulterville Road and the Big Oak Flat Road were completed to the Valley floor. There was great rejoicing when the first stages rolled down the grades to the Valley floor, and all the country-side greeted the day, June 17, 1874, as heralding a new era for Yosemite. In 1875 the Wawona Road was built to the Valley and again great rejoicing followed among the communities favored by this new service.

With the advent of travel by stage-coach and wagon the first period of Yosemite history comes to an end; the next period is a chapter by itself, lasting until the automobile arrived to bring about still greater changes.

Carl P. Russell.

__________

1 Bunnell, Discovery of the Yosemite, 1880, p. 315.

2 Early History of Yosemite,” in The Grizzly Bear, July, 1919; reprinted by U. S. National Park Service.

4 Kuykendall (U. S. N. P. S. edition), p. 10.

5 Hutchings, In the Heart of the Sierras, 1886, pp. 79-80.

6 The famous Ayres’ drawings made in Yosemite in 1855 have been presented to the Yosemite Museum. In the more than seventy years that have elapsed since they were created, they have journeyed on pack mules, sailed the seas in old U. S. Men of War, jolted about in covered wagons, and at last made a transcontinental journey in fast express trains to come again to the wonderful valley that gave them birth.

In 1853, James Alden, then a commander in the U. S. Navy, came to California on a commission to settle the boundary between Mexico and California. He remained until 1860. Some time between 1856 and 1860 he visited Yosemite Valley. Probably on his return to San Francisco he came upon Ayres’ drawings, which appealed to him as the best mementos of his Yosemite experience, and he procured ten originals and one lithograph. Recently Mrs. Ernest W. Bowditch, Mrs. C. W. Hubbard, and Mrs. A. H. Eustis, descendants of Admiral Alden and heirs to these priceless pictures, have presented them to the Government Museum, which stands near the spot where some of them were made.

7 Country Gentleman, October 9, 1856. [Editor’s note: the correct date is October 8, 1856—dea.]

8 Bunnell (1880), Chapter 19. — Whitney, Yosemite Guide Book, 1871, p 19. — Hutchings, In the Heart of the Sierras, 1886, p. 101.

9 Hutchings. [Guide to] Yo Semite Valley and the Big Trees, 1895, p. 56.

See introduction to One Hundred Years in Yosemite by Carl P. Russell

Carl Parcher Russell (1894-1967), “Early Years in Yosemite,” California Historical Society Quarterly 5(4):328-341 (December 1926).

Digitized by Dan Anderson, December 2005,

from a copy at the UCSD Library.

—Dan Anderson, www.yosemite.ca.us

Copyright status: This article is in the public domain, as it was published over 95 years ago.

| Ebook formats | No images: | Plain text zip | Plucker | HTML zip | Palm Doc | Palm zTXT | Sony LRF | Braille Grade 2 BRF |

| Images: | Plucker | iSilo | Kindle/Mobipocket |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/early_years_in_yosemite/