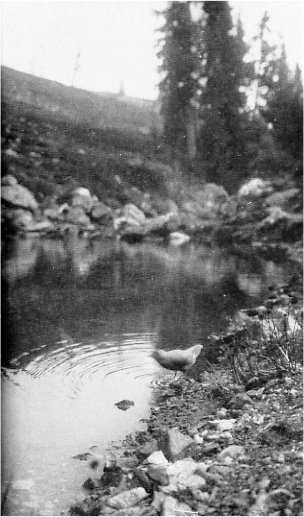

PLATE VIII

Male Western Warbling Vireo on the nest, singing while

performing the duty of incubation. This is one of the

common summer visitant birds of the Park

Photo by Henry J. Rust

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Handbook > Birds >

Next: Mammals of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Life Zones of Yosemite

By Joseph Grinnell,

Director,

and Tracy Irwin

Storer,

Field Naturalist, Museum of Vertebrate

Zoölogy, University of California

(Contribution of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoölogy of the

University of California)

The West is often commented upon as a region scant in bird life, yet the "Yosemite section" alone, comprising an area of about fifteen hundred square miles, a little greater than that of the State of Rhode Island, has been found to harbor no less than 226 different varieties of birds. Of these, 199 are "full species." Nor are restricted localities within this area lacking in their quotas; Yosemite Valley, far off the general routes of bird migration, can already be credited with a hundred different kinds. Daily censuses checked by us hour by hour prove birds abundant there in early summer as to both species and individuals. A four-hour tally in Yosemite Valley on May 31, 1915, revealed 32 species and 220 individuals; a five hour walk in the western foothills near Pleasant Valley a week previously showed 48 species and 490 individuals.

Of all the birds in the Yosemite National Park the Western Robin least needs introduction. Soon after leaving El Portal on the stage, or upon entering the yellow pine belt along the Wawona, Big Oak Flat or Coulterville Road, the visitor will catch sight of the familiar Robin as it forages in some open glade or sings from a perch in some roadside tree. It occurs throughout the mountain forest belt, in the Transition, Canadian, and Hudsonian zones, chiefly about grassy meadows and clearings. The mud-cemented nests are built for the most part in early May, and the spotted young appear by June. In fall And winter the Robins gather in flocks and wander widely as they seek out the then ripening berry crops. They desert the higher mountains at this season going to the foothills and lower valleys; after the first snow fall of the season, only a few remain in Yosemite Valley.

An associate of the Robin is the Sierra Junco or Snow-bird which does its foraging likewise around openings in the forest or along the banks of open flowing streams. The Junco has a black "cowl" covering head, neck and breast, a white-appearing bill, a dark back and wings, and white belly. As it hops about, the tail is opened momentarily and when the bird flies this member is spread widely, showing a conspicuous white margin which forms with the other features a ready recognition mark for the bird. The male Juncos sing from perches in the trees. Nests are built upon the ground where the birds seem not less successful in bringing off their young than the Robins which place their nests in trees. The juncos stay in pairs during the summer, but they band together at the coming of fall and go to the foothills in flocks of twenty-five or more.

The Robin about ten inches long, and the Junco six inches from bill to end of tail, may be taken as standards of size comparison for other birds of the region. Both of these species are common in Yosemite Valley,

PLATE VIII Male Western Warbling Vireo on the nest, singing while performing the duty of incubation. This is one of the common summer visitant birds of the Park Photo by Henry J. Rust |

A small Finch found numerously in summer in Yosemite Valley is the Western Chipping Sparrow. Smaller than a Junco, with a bright chestnut cap, a whitish line over the eye and streaked back but plain under surface, it is sure to come early to attention, and in May and June its nests will be found in the pine saplings and deer-bushes on the Valley floor. The "chippies," like the Juncos, form into flocks before they depart westward and southward for the winter.

The small birds of bright and contrasted coloration known as wood warblers are important members of the Sierran avifauna. The Audubon Warbler, of varied body plumage but always exhibiting a yellow rump and white spots on the outer tail feathers, is the most widely distributed species of the group. It occurs in the coniferous trees of the Transition, Canadian, and Hudsonian zones during the summer, and winters in large numbers in the foothills west of the park boundary. This species both nests and forages twenty to fifty feet above ground in evergreen trees. A somewhat rarer species not occurring much above the Transition Zone is the Hermit Warbler, which has a dark body and rump, yellow head and black chin and throat. It forages amid the same sort of surroundings as the Audubon Warbler. When once learned, their songs, alone, distinguish them. The Black-throated Gray Warbler is a species practically restricted to the golden oaks which grow in profusion on the talus heaps and ledges along the north and south walls of Yosemite Valley. It is a bird of deliberate mien and drawling song and its coloration shows no obvious yellow. The other warblers of the park are yellow-bodied in the main. In the willows and cottonwoods lining the Merced River from Snelling up into Yosemite Valley is the California Yellow Warbler. The black oaks of the Valley floor harbor the grayish-headed Calaveras Warbler, which seeks a site upon the ground for nesting, while in the moist thickets in the Yosemite is to be found the dark- "cowled" Macgillivray or Tolmie Warbler. In the Canadian Zone above the rim of the Yosemite gorge is the Golden Pileolated Warbler, a brilliantly yellow bird with a shining black crown patch. It stays in the creek dogwood and willows which grow in the wet meadows and along rushing streams. All of these warblers are absent from the mountains during the winter months; their food being almost exclusively of insects is available here in adequate quantity for their sustenance only during the summer season. Each of our Warblers has a set song delivered persistently in the spring months. But despite their cognomen of "Warbler" they do not compare as musicians with many of the other forest songsters in either quality, extent, or variety of song.

It is to be expected that "birds of prey" abound in a region so well stocked with the smaller birds and animals as is the Yosemite section. A dozen kinds of hawks and nine different species of owls have, indeed, been found here. Space limits us to detailed mention now of only a f ew of these. The Golden Eagle is supreme in size and in majesty of bearing among all the Sierran land birds. It is most common in the western foothills but is fairly well represented up into the highest passes of the Sierra Nevada. The Golden Eagle measures thirty to thirty-five inches in length, with a wing spread of six to seven feet. The least glint of sunlight on the bird’s head and neck reflects a golden brown tint, and this feature accounts for its name. The Red-tailed Hawk is found throughout the mountain country, and in summer the misnamed Sparrow Hawk visits the higher meadows and ridges even above timberline to search for grasshoppers.

The clear cool mountain air lulls so many Yosemite visitors to an early sleep that only the exceptional person will note the flitting forms or measured hoots of any of the owls in the region. The smallest of these birds, the California Pigmy Owl, is perhaps the most likely one to be heard, because it begins calling at early dusk and often continues in voice long after daybreak. It is only about seven inches long, has a rounded head without ear tufts, yellow eyes, and a dark brown back. It inhabits sparse woods and is the commonest owl in Yosemite Valley. Its call is quite distinctive, a trilled tooting which lasts several seconds, a pause, then a single note, another pause and then a second note, too-too-too-too-too-too-too-too-too; whoot; whoot. Sometimes a deep reverberant whoo, whoo, who-hoo comes from the taller trees, indicating the presence of the big Horned Owl; and on occasion one may hear, in Yosemite Valley, the dog-like yelping and barking of the rarer Spotted Owl.

The Yosemite visitor who has read John Muir’s splendid and appreciative description of the Water Ouzel or Dipper in his book The Mountains of California will be keen for a personal acquaintance with this singular inhabitant of the Sierran creeks and rivers. A morning along any of the streams in the park is likely to reveal a chunkily built bird of slaty gray coloration which is jouncing about this way and that on some rock in midstream or flying from one such perch to another. Suddenly, the bird disappears beneath the stream, and one wonders with apprehension at its fate in that rushing torrent; but speculation is dispelled when the Dipper reappears in a few seconds up or down stream and resumes its "dipping" on another rock. This one-time land bird, relative of the wrens and thrushes, has taken to living about, in and under the water. Its nest is placed along the stream, usually in a niche of the rock where touched by light spray, so that the mossy exterior of the structure is kept wet and growing while the birds are rearing their brood. The Dipper’s song is among the most striking of all mountain bird voices, and while given through much of the year, it appeals best when other songsters are gone or quiet, during the snowy winter.

The swift flowing waters of the Merced and Tuolumne rivers offer attraction to but few water birds, but wherever the banks are low and covered with sand or gravel there may be expected the Spotted Sandpiper. Lagrange, Yosemite Valley, and Tuolumne Meadows are but three of its several known haunts within the Yosemite section. In summer the pairs are busy with their nesting duties, and their clear calls ring out at all times of the day as the birds trot along the strand or fly in semicircular course from place to place along the shores in search of food. These are typical "shore-birds" and their nest consists of little more than a depression in the gravel large enough to shelter the four good-sized eggs.

The mountain forests furnish the homes of many different kinds of Woodpeckers. The Yosemite section has thus far revealed no less than twelve species, some in the foothills, some in the high mountains, others encompassing both these habitats. At middle altitudes, in Yosemite Valley and the Canadian Zone above, is the White-headed Woodpecker which is solidly black except for a pure white head and small patch of white on each wing. It might be thought that a bird of such coloration would be conspicuous, but the very reverse is true; these colors blend exceedingly well with the background whether this be formed by the bleached or blackened stumps, or the high lights and shadows on the living trees. The Whitehead nests usually within twelve feet of the ground, by preference in a shattered stump or in an upstanding branch of a prostrate trunk. During the late spring and early summer months its domestic program is thus capable of easy study.

"Cock-of-the-Woods" is an appropriate name given to the Pileated Woodpecker, the giant among all the local Woodpeckers. It measures over seventeen inches in length as compared with the twelve inches of the well-known Red-shafted Flicker. A bird of black body, it shows white in large patches on both outer and inner surfaces of the wings and a stripe of white on its neck, while the head bears a flaming red crest. This Woodpecker occurs at times in Yosemite Valley, but his kind is more abundant in places of greater altitude where there are numerous dead stubs of red or white fir to be prospected for grubs or, in spring, to be excavated for nesting places. When at work the noise produced by the Pileated’s big chisel-like beak sounds like the strokes of a distant woodchopper or the blows struck by a telephone repair man. When on the wing the Pileated Woodpecker pursues a nearly level course, flashing the white wing patches regularly, and often uttering a sustained and far-carrying kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk.

The California Woodpecker, so common in the California valleys and foothills, reaches the oak-dotted floor of Yosemite Valley in fair numbers, and its work may be seen in many places there. This is "el carpintero" of the Spanish explorers, the bird which stores for itself a supply of acorns, wedging each into a newly dug pit in the bark of some convenient oak or pine tree. Certain big trees in Yosemite Valley are studded with acorns for many feet from the ground. With golden oaks on the talus slopes and black oaks on the Valley floor the birds should never be at a loss for their favorite nuts. Yet another type of food is needed, for in summer they are regularly to be seen flying out from exposed perches to capture passing insects.

Over the open gorge of the Yosemite and from most of the "inspiration" points about the rim, may be seen every day of the summer season, the "policemen of the upper air," the Swifts and Swallows. The dark-bodied form, of crossbow outline, which cuts the air at lightning speed is the White-throated Swift, and its more leisurely associate, which displays a pure white under surface, is the Violet-green Swallow. The Swift is of about twice the bulk of the Swallow, its proportionately narrower wings are concave instead of straight-margined behind, and it is much more swift and daring than the Violet-green; when flying it often utters a torrential series of notes. louder and more hurried in delivery than any calls given by swallows.

The Band-tailed Pigeon, western counterpart. of the now extinct Passenger Pigeon, is found in fair numbers in the Yosemite region practically throughout the year. Yosemite Valley harbors one or more flocks of these birds, and while acorns constitute their main source of food, toyon and coffee-berries, and scattered grain in the poultry yards of indulgent residents of the Valley afford the birds forage when the first named staple is scarce or wanting. The bluish gray back, pinkish breast, and dusky-banded tail are color features to be looked for. The big birds are often unnoticed amid the oak foliage until they flush with a loud clapping of wings and make off in swift course to some other retreat.

At the lower limit in scale of size among Sierran and indeed all Californian birds is the Calliope Hummingbird, the little green and violet-feathered jewel, which flits lightly about the flowers of the mountain meadows. This midget, weighing about one-tenth of an ounce (3 grams), is but a summer visitant here and winters in Mexico. The thickets of Sierran currant break into blossom in the Canadian Zone during May or early June. The Calliopes at the same time appear in numbers, the males foraging and battling with one another on the upper slopes while the females stay down toward the canyon bottoms preparing to rear their broods. The "gorget" of iridescent hues on the throat of the male consists of long lance-shaped feathers which in display are held out apart from the snowy white color of the neck. This is the only Hummingbird which, so far as we know definitely, nests in the park; the Anna and Black-chinned occur in the western foothill country as far up as El Portal, and the Rufous Hummingbird passes south along the Sierras in July and August.

From early morning until late dusk, throughout the mountain forest belt, is to be heard the droning zuweez of the Western Wood Pewee. This is the commonest and most widely distributed member of the flycatcher family although other species of the group occur in numbers in appropriate places in the Yosemite section. The Pewee is a bird of open forest, usually perching fifteen to forty feet above the ground in a place where it has a clear view of its surroundings. The bird sits quietly, but its head turns this way and that as it watches for passing insects. These are captured by short quick sorties, the Pewee returning to the same or a nearby perch after each pursuit. The Pewee is plain dark brown above and on the sides of the body, with yellowish white on the middle of the lower surface. The larger Olive-sided Flycatcher which chooses the lofty tree-tops as lookouts has whitish flank patches and a loud three-syllabled call; and the small weak-voiced flycatchers have light eve rings and light bars on the wings.

About the same time that the newly arrived visitor sees his first Robin, another, even bolder member of the mountain avifauna will likely force itself upon the attention. This is the Blue-fronted Jay, local representative of the crested or Steller Jays of western North American generally. It is a common resident of the Transition and Canadian zones of the park. The bird spends most of its time in the trees; a favorite perch is near the top of a tall conifer from where it can see all that goes on in the forest. When ascending to such a station the bird will keep close to the trunk, hopping up and around from one branch to another as if following a spiral staircase. In nesting time the two members of a pair keep close together. While ordinarily noisy, a "zone of quiet" is maintained about their own nest. At this season they are wont to raid the nests of smaller birds carrying off the eggs or young to serve for their own food; the small parents

PLATE IX The Water Ouzel Photo by Gertrude Metcalfe Sholes |

The "high Sierra" has its component of bird life, smaller to be sure in both species and numbers than the lower, more thickly wooded areas, but containing a number of distinctive types worth a long hike to get acquainted with. The Clark Nutcracker, a member of the Crow Family, and the local "camp robber," is a denizen of the Hudsonian Zone, sometimes ranging down to the upper limits of the Transition, and again and more often up above timberline. It wears a pied plumage, gray on the body with black flight feathers, while each wing shows a white spot, and the tail a broad white margin when the bird takes to flight. The daily round of foraging after pine seeds either in the trees or on the ground beneath soon results in the plumage acquiring a brownish overtone due to pitch, and after the birds have gone through with the duties of the nesting season (March to May) some individuals present a bedraggled appearance indeed.

Early summer visitors to the Canadian Zone are likely to hear a song of exquisite beauty coming from the top of some lofty fir or pine. Interspersed between the warbling strains are numerous metallic clinking notes resembling a ground squirrel’s whistle. All of these are from the repertoire of the Townsend Solitaire, in several respects an unique member of the Thrush Family. The Solitaire is a grayish bird of slender form and long tail. When it takes to flight one sees a light margin to the outer tail feathers and a broad yellowish bar upon each open wing. One would search the trees in vain for this bird’s nest; the tree-tops are used only for singing and foraging. At nesting time a sheltered spot on the ground is selected, such as the base of some uprooted tree or a niche in a roadside bank, and here a nest of loose construction, with many pine needles and twig-ends straggling below it, is placed. In the fall the Solitaires range over the country widely, going here and there after berries of juniper, toyon, and mistletoe, which furnish their sustenance in the colder months of the year.

Two Thrushes occur in the region during summer, the larger and more plainly garbed Russet-backed, rather sparingly and chiefly in the Transition Zone, and the Sierra Hermit Thrush, vesper songster in the wooded glades, which is found in Yosemite Valley but more commonly in the zones above. The latter, told at once by its rather bright "rufous" rump and tail, has a peculiar habit of twitching or refolding its wings at short intervals and slowly depressing the tail at the same instant. It keeps close to the stands of small dense conifers in canyon bottoms whence its song of set theme but much varying key comes at short intervals, especially in the morning and evening hours of twilight.

The Sierras possess three distinct Grosbeaks, two of which are resident at high altitudes practically throughout the year. In the Hudsonian Zone is the rather rare California Pine Grosbeak, a gray bird of slender appearing body and long tail. The females and young are "washed" with yellow on the head and breast while the adult males are brilliant red over nearly the entire body. In the Canadian and Transition zones one is likely to see the more chunkily built and vari-colored California Evening Grosbeak. This bird has a huge greenish yellow bill. The body plumage of the male is yellow, the tail and wings black with a large patch of white along the inner margin of each wing. The female is gray with scattered white markings on the dark flight feathers. Neither of these Grosbeaks is an elaborate singer; their best efforts are little-more than a repetition of the high-pitched call notes.

The Black-headed Grosbeak, one of the largest and most strikingly colored of the finch and sparrow tribe, has gained a special reputation in Yosemite Valley by reason of i ts habit of appropriating butter and other viands from tables set beneath the trees. The plumage of the male is varied with black, brown, and white, while the female is much streaked, especially about the head. In May and June these Grosbeaks are in full voice in Yosemite Valley. Novices confuse the song of this Grosbeak with that of the Robin, but the former is fuller and quicker, with many little trills and warbles not heard in the Robin’s rather monotonous carol. The Black-headed Grosbeak builds a simple nest, little more than a cupped platform of fine interlacing twigs, and. often so thin that an observer standing on the ground can look through the bottom and see at least the outline of whatever it contains.

The brush belt of the Canadian Zone with its manzanita, snow bush, chinquapin, and huckleberry oak is the home of a big, ground-dwelling type of Finch, the Fox Sparrow. Winter or summer, birds of this sort are there, though the race represented, and of course the individuals, change with the season. In summer there is the grayish toned race called Yosemite Fox Sparrow while winter sees this variety replaced by brown backed birds from the Alaska coast. All are alike in being ground foragers, who kick and dig with their stout feet in the leafy waste, sending up little jets of débris with an accompanying noise out of all proportion to the size of the bird, and such as sometimes frightens timid walkers along the trails who suspect some lurking wild beast. Passing these thickets in summer one is apt to hear the clear ringing lay of the bird, and if one camps near a ridge top touched early by the morning sun, he will likely be awakened by the songs of the Fox Sparrows who have moved upslope to catch these first warming rays after a chilly night.

Often while traversing trails through open forest, there comes from the tree tops a quaint, nasal weh, weh, weh—syllables which sound like the blasts of an elfin horn. Search as he may, the traveler will at best locate a small form moving about the trunk and limbs near the tiptop of the tree. If luck and patience favor, the bird may come low enough so that its grayish back, black head with light stripe over eye, reddish under surface, and very short squared tail show it to be a Red-breasted Nuthatch. The bird forages exclusively on the bark, hunting out insects which have secluded themselves in crevices. In moving about, the Nuthatch goes either up or down, with seemingly equal facility. The Slender-billed Nuthatch, western relative of the White-breasted of the East, occurs at lower altitudes, and occasionally, in the yellow pine belt, a troop of the Pygmy Nuthatches may be encountered.

Each part of the tree receives attention from some particular type of bird. Kinglets and Warblers search the foliage, Vireos the smaller twigs, Woodpeckers seek grubs buried within the wood, while Nuthatches and Creepers scrutinize the bark of trunk and limbs. The Sierra Creeper, the local variety of an almost world-ranging species, is found on the forest trees of the Transition and higher zones. The Creeper wears a streaked brown pattern of color on the back and the under surface is white; its tail feathers are long-pointed and stiffened so as to give the bird support as it clings to the side of a tree. Unlike the Nuthatch, the Creeper moves only upward on the trunk; it ascends from the base, often spiralling around the trunk, and when it arrives at the top of one tree it flies off to the base of another. Its call is fine and wiry and the song is but little more than several of these faint high-pitched notes in quick succession.

Chickadees are associated in the mind with forests, and in the Yosemite region is to be found the Mountain Chickadee, inhabitant of the woods, throughout the Transition and Canadian zones. Memories of the plainly pronounced chick-a-dee-dee and of the clear whistled song remain long in the minds of travelers who visit the California Sierras. In fall and winter the birds go about in companies but in spring these companies break up into pairs, and by early May the nesting duties are begun. First comes selection of a nest site, usually an old hole of the White-headed Woodpecker. This chosen, it may be remodelled or cleaned out somewhat, when it is lined with feathers and hair, and then five to eight eggs are laid. When the brood is hatched and grown they fairly fill the cavity, and anyone who has taken out a family of Chickadees to make their portraits will attest to the impossibility of being quite able to fit them back into the nest hole again. The Mountain Chickadee remains in the Sierras through the winter, and its familiar call is one of the few bird notes to be heard when the Yosemite Valley is blanketed with snow.

Along the streams at middle altitudes in the Transition and Canadian zones one is sure to hear, during the early summer months, the pleasing song of the Western Warbling Vireo. Many birds sing only at morning and evening, a few chiefly during midday, and some of those who keep up their songs and calls throughout the day soon weary the human hearer; but all this does not apply to the Western Warbling Vireo. Even during afternoons of drowsy heat we have heard these birds in almost continuous song. Singing does not hinder the birds in the performance of their regular duties, for we have seen one carrying material and building its nest while it sang, and it is commonly known among bird students that this Vireo sings regularly while sitting upon its eggs.

The open grassy areas of the Hudsonian Zone, such as those which constitute Tuolumne Meadows, afford an abundant supply of insect food for a brief period during the summer months, and several birds migrate to these high mountain locations to take advantage of this ephemeral food supply. The Mountain Bluebird is one of these summer visitants to the high Sierras. Paler in tone of blue than either its relative of the California foothills or the Eastern Bluebird, this species in its coloration reflects the intense lights and pallid tones of the high mountains. When the first mountaineers of the season reach the alpine meadows, pairs of Mountain Bluebirds are preparing to nest, seeking old woodpecker holes or similar cavities of dead trees. By July the young are hatched and then the parent birds busy themselves hunting insects in the fast growing grasses of the meadows. A favorite method with this bird is to hover in one place with rapidly beating wings ten to twenty feet above the ground and intently scan the turf below for prey. When an insect is spied the bird drops rapidly to the surface, captures the object and then makes off with it to a perch or to the nest.

From well up in the forest trees there comes during the spring and early summer a clear song of considerable volume which seems to say, 0, Oh-Oh, Cheerily, Cheerily, Cheerily. One would be tempted to look for a bird of considerable size, but the songster is actually one of the smallest in the mountains, the Ruby-crowned Kinglet. There are two species of the diminutive Kinglets with bright crown markings, in our mountains. The Ruby-crown has a red crown patch present only in the male. This is normally concealed by the other feathers of the head but can be flashed forth with startling effect when the bird is excited. The Golden-crowned Kinglet on the other hand wears a yellowish crown patch bounded by black. It is present in both sexes and in both is held permanently in view. In addition to its pleasing song, the Ruby-crown gives a loud sputtering note or "ratchet-call" which it utters when excited over any unusual event such as the appearance on the scene of a Bluejay or Owl.

Surely the visitor who really looks for birds in the Yosemite region will not be disappointed. For the experience of those who have already made fair trial has proven the richness of the possibilities here. And these possibilities are far from exhausted; new discoveries are sure to reward careful search for many seasons to come.

Bailey, F. M., 1917. Handbook of Birds of the Western United States. (7th ed., rev., Boston, Houghton Mifflin Co.) liv+574 pp., 36 pls., 601 figs. in text.

Emerson, W. O., 1893. "Random Bird-Notes from Merced Big Trees and Yosemite Valley." Zoe, vol. iv., July, 1893, pp. 176-182.

Grinnell, J., "Early Summer Birds in Yosemite Valley." Sierra Club Bulletin, vol. viii., June, 1911, pp. 118-124.

Grinnell, J., 1915. "A Distributional List of the Birds of California." Pacific Coast Avifauna No. 11, 217 pp., pls. I-III. (Published by Cooper Ornithological Club, Berkeley, Calif.)

Grinnell, J., Bryant, H. C., and Storer, T. I., 1918. The Game Birds of California. (University of California Press, Berkeley) x+641 pp., 16 col. pls., 94 figs. in text.

Keeler, C. A., 1908. "Bird Life of Yosemite Park." Sierra Club Bulletin, vol. v., January, 1908, pp. 245-254.

Mailliard, J., 1918. "Early Autumn Birds in Yosemite Valley." Condor, vol. xx., January, 1918, pp. 11-19.

Muir, J., 1894.

The Mountains of California. (New York , The

Century Co.) xv+381 pp., 53 illus.

1898. "Among the Birds of the Yosemite." Atlantic

Monthly, vol. lxxxii., December, 1898, pp. 751-760.

1901. Our National Parks.

(Boston, Houghton Mifflin

Co.) 10+370 pp., frontispiece, map, 10 plates.

Ray, M. S., 1898. "A Summer Trip to Yosemite." Osprey, vol. iii., December, 1898, p. 55.

Torrey, B., 1913. Field-Days in California. (Boston, Houghton Mifflin Co.) 10+235 pp., 9 pls.

Widmann, O., 1904. "Yosemite Valley Birds." Auk, vol. xxi., January, 1904, pp. 66-73.

Next: Mammals of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Life Zones of Yosemite

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/handbook_of_yosemite_national_park/birds.html