[Editor’s note: Susie McGowan with daughter Sadie, Mono Lake Paiute. From J. T. Boysen photo, c. 1901 —DEA]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Handbook > Indians >

Next: Ideals and Policy of the National Park Service • Contents • Previous: History of Yosemite

[Editor’s note: Susie McGowan with daughter Sadie, Mono Lake Paiute. From J. T. Boysen photo, c. 1901 —DEA] |

By A. L. Kroeber

Professor of Anthropology and Curator of the Anthropological

Museum, University of California

The Indians of Yosemite belong to a group or family known as the Miwok who, before the white man came, owned the tract from the Cosumnes River on the north to the Fresno on the south, and from the crest of the Sierra Nevada to the edge of the San Joaquin Valley. The name Miwok is not strictly a tribal appellation; it is simply the word in the language of these Indians which means "people." In default of any specific designation for them, this term Miwok has been applied in distinction from other groups of aborigines. Of such groups, there may be mentioned as neighbors: the Maidu to the north in the Sierra; the Yokuts to the south in the foothills and to the southwest in the San Joaquin Valley; and the Mono to the south in the high Sierra, and to the east in Owens Valley and about Mono Lake. Excepting the Mono (who are an offshoot from the Paiutes and other Shoshoneans of Nevada and the Great Basin country) the other groups of Indians adjacent to the Miwok are very similar to them in physical type and customs, and even show a probable, although distant, relationship to them in speech. In short, the Miwok are typical and representative California Indians, and in this capacity form part of the large body of tribes known as "Diggers." This is, however, a misleading name; partly because it carries a tinge of contempt, and still more because it lumps together a variety of nationalities that sometimes differed pretty thoroughly in their speech or were even unaware of one another’s existence. For this reason the more accurate terms Miwok, Maidu, and Yokuts are preferable.

The origin of these Sierra Nevada tribes is not definitely known. There can, however, be no serious doubt that they form part of the generic American Indian race and that their ultimate origin must be sought wherever the source of this division of mankind may have lain. While no one is yet in a position to speak dogmatically on this matter, all indications point to the Indians having come at some time in the far past from Asia, probably by the Bering Strait and Alaska route. It is clear that in his bodily type the Indian more nearly resembles the Mongolian of Eastern Asia than any other variety of the human species. The long, straight, stiff hair, one of the most valuable marks in race classification, is alone sufficient to establish a strong presumption in this direction. As to when this migration of the first inhabitants of America out of Asia took place, there is growing up a fairly unanimous concensus among anthropologists that this movement must have occurred at about the time that the Old Stone Age was giving place to the New in Europe; that is to say, in the period at which chipped stone tools were being replaced by polished ones, and the ax, bow and arrow, textiles, agricultural implements, and domestic animals were becoming part of the heritage of the species. These steps in advance are believed to have occurred about ten thousand years ago. We may therefore say roughly that somewhere about 8000 B.C.—with an allowance of a few thousand years either way as a margin for error—the American Indian became established on this continent and began his diffusion.

California was probably not very long in being reached; a mode of life adapted to local conditions was worked out, and with this the natives were apparently content, and their development progressed only slowly. They have left some traces of their occupancy in ancient village sites, shell mounds, and the like. Here the less perishable of their utensils, such as mortars, pestles, pipes, knives, arrow points, awls, beads, and other objects of stone, bone, and so forth, have been preserved. In one of the most favorable localities on the shores of San Francisco Bay careful computations have been made as to the age of these deposits, with the result that the lower levels of the shell mounds there have been estimated to date back at least 3000 years. The implements at these lower levels are ruder than those found near the tops of the mounds; but they are after all of the same type and even rather similar to those used by the modern Indians of the State, including the Miwok. We are therefore justified in assuming that native customs evolved very slowly in California, and that the ancestors of the Miwok and of the Yosemite Indians for a very long time past have lived very much in the manner and under the conditions in which they were discovered by the whites seventy years ago.

The Miwok probably numbered at least ten thousand, but the population decreased with terrifying rapidity after the advent of the white man. Some of the nearer groups of them were taken to the Franciscan Missions on the coast and there died off or became mixed with other tribes. The miner and rancher quickly overran the Miwok habitat after 1849. The Indian was crowded into the less desirable nooks; his native food supply was preëmpted; whiskey and new diseases against which he had no immunity were introduced and resulted in a startling mortality; and the general change in mode of life—new types of habitations, clothing, diet, labor, etc.—accentuated the effect of these diseases. The consequence was that in the sixty years between their first serious contact with the white man until the census of 1910, the Miwok lost more than ninety percent. of their numbers. This census, which may not be wholly complete but was by far the most accurate ever made as regards Indians, enumerates only about seven hundred of them, and of these a fair proportion are mixed bloods. The number is still shrinking, but fortunately with less rapidity than formerly. The Indian has begun to adapt himself to civilized life, and has acquired some resistance to our diseases. The Miwok therefore bid fair to maintain themselves as a diminishing remnant for some time longer, and quite likely even a small fraction of them may survive permanently.

The Miwok were not divided into tribes in the usual sense of the word. They recognized very little political authority. They were broken up into small local groups, little larger than village communities, each of which admitted the headship of some chief and allowed im a rather poorly defined amount of influence on their conduct. These numerous little bodies named each other, generally, after the localities which they inhabited. Thus the Yosemite Indians as a body were ordinarily known to the other Miwok as the Awanichi, after Awani, the largest or best known village site in the Valley, located not far from the foot of Yosemite Falls. In the same way a group south of Yosemite was called the Pohonichi, because in summer they ranged northward to the Valley in the region of Bridalveil Creek, the famous falls of which are known as Pohono.

The Yosemite Indians were in the hunting stage; that is, they never farmed nor raised domestic animals. Actually, however, only a small part of their diet came from game. They probably took as many pounds of fish each year as of animal flesh, and a still larger portion of their food was wild vegetable products. Among these the acorn was preëminent, and even to-day the caches or bins for the storage of these nutritious nuts can occasionally be seen in the Valley. These are rude affairs, eight or ten feet in height, constructed of brush much like a long and deep bird’s nest, and set between four or five posts to keep the receptacle and its contents off the ground. They fulfill their function of food conservation with only moderate success, since one rarely approaches one of these caches without seeing a squirrel run out from a hole which it has wormed through the brush walls. Acorns, however, are plentiful in most parts of California and before the American introduced hogs they were superabundant, so that the Indians could afford to share part of their crop with these unbidden visitors and still have enough left for their own needs.

Acorns contain more or less tannin. The Indian women leached this out with hot water after the nuts had been shelled and pounded with a pestle in a stone mortar. The latter usually was nothing more than a hole in the surface of some convenient outcrop of granite. Frequently a number of these mortar holes were assembled in one spot; these were roofed over with branches, and in the shade of such an arbor the Indian women were wont to gather for hours at a time to wield the heavy pestle and meanwhile indulge in the gossip of which they were not less fond than their Caucasian sisters. After the acorns were pulverized, the meal was sifted and then cooked in baskets into a thin mush or gruel—the famous "acorn soup" which was the staff of life to most of the California Indians. As pottery and iron vessels were unknown, cooking had of necessity to be done in water-tight baskets. A basket cannot of course be set over a fire, so the Indian woman had perforce to bring the fire into her food, as it were. This she did by heating stones about the size of her fist, picking these up with a pair of sticks, and dropping them into the liquid, to which they communicated their heat until the mass boiled, The stones were then removed and the gruel was ready for consumption.

At least fifty to a hundred other varieties of food plants were utilized. Among the more important of these were buckeyes, which contain a narcotic poison that is removable by leaching like the tannin in the acorn; chia, a variety of sage the seeds of which can be

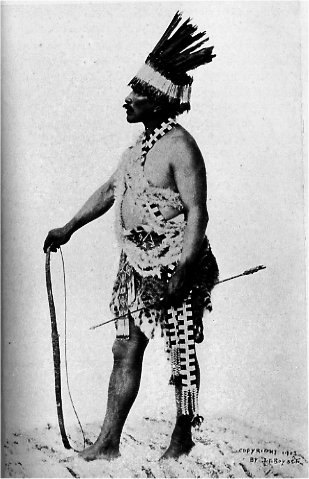

PLATE IV Francisco, a Yosemite Indian, in dance costume. The crown is of magpie feathers, the headband of yellow-hammer feathers, and the white ropes about the body chiefly of eagle down. The kilt is a wild cat skin with bead trimmings Photo by J. T. Boysen [Editor’s note: Francisco Georgely was Northern Yokuts from Chowchilla. —DEA] |

The Miwok bow was from three to four feet long and had its back heavily covered with a layer of sinews to give added toughness and elasticity. It was a rather narrow weapon, and the sinew was thickened at the ends and then curled back on itself in a characteristic shape. Such at least was the bow used in warfare and for hunting large game. For rabbits, gophers, and birds, which can be approached closely, a ruder weapon without the sinew backing sufficed. For such purposes, too, the arrow was often a mere shaft, whereas the real hunting and war bow shot arrows which were foreshafted and tipped with delicate points of flint or obsidian. The latter material, a blackish, volcanic glass, the Miwok obtained by trade from the Mono Indians.

With all its inferiority to firearms, the bow is a powerful instrument within its effective range. A good weapon speeds an arrow with an initial velocity of 120 feet per second. It has definite killing power up to fifty yards, and at double that distance can easily inflict wounds that subsequently prove fatal. It tears the tissues more than a modern bullet, and frequently produces internal hemorrhages from which the victim bleeds to death, or which so weaken game that it can be followed up and overtaken. The longest attested flight for an arrow is more than a quarter of a mile, but this record was made with a composite Turkish bow and especial long range arrows. The Indians never attempted shooting over such distances. They depended rather on knowing the habits of deer and elk and creeping up on them. A favorite device was for the hunter to cover himself with a deer hide and set on his head a stuffed deer’s head. In this way he attracted the curiosity of his quarry without alarming it, and was often able to approach very close to it.

When the Miwok fought, which was not very often, it most frequently took on the form of a feud for revenge. They usually shot at each other at fairly long range; enough, at any rate, to make possible the dodging of arrows. Each line of warriors therefore capered and danced about to render it difficult for their opponents to take aim, and jerked forward and sidewise as they saw arrows coming. As might be expected, casualties were rather light. It was only when one party could ambush another, or pounce on a settlement asleep just before daybreak, that fatalities would run high.

The houses of the Yosemite and other Miwok Indians were rude affairs, built, according to location and abundance of materials, either of thatch, slabs of bark, or with a covering of earth. In Yosemite itself the cedar-bark house predominated. This was a conical lean-to with the slabs laid on several deep, and while not entirely wind-proof it afforded reasonable shelter. Most of the huts were small, probably not over ten or twelve feet in diameter. One or two of them may still be seen at the time of this writing, though they present rather a sorry appearance of gunnysacks, worn-out quilts, and pieces of sawn lumber mixed in with the bark slabs.

In the lower foothills, the native house was more frequently of the wigwam type, thatched with grass, rushes, or brush; and in parts of the San Joaquin Valley the earth lodge was typical. This was more or less excavated and covered with a heavy layer of earth laid on a roof of poles and brush supported by stout timbers. The Miwok used the earth lodge mainly for their dance- and sweat-houses. The former were large affairs up to forty or more feet in diameter. The latter were much smaller edifices in which the men daily sweated themselves for their health and physical comfort. The Yosemite Indians were about at the edge of the habit of building earth-covered dance houses. The more northerly Miwok and the tribes beyond used them regularly in every village of any consequence, whereas the Yokuts, to the south of Yosemite, did not erect earth lodges.

The word "Yosemite" means Grizzly Bear in the Miwok language. Its more exact form is "üzümati" or"ühümati." The name became definitely attached to the Valley, and to the band of Indians that made it their headquarters, from the time of their first contact with Americans. There are several explanations. One story has it that an unarmed young Indian fought off a fierce grizzly bear with only a stick, and that this exploit led to the adoption of the name as a sort of heraldic crest by his group. Somehow this legend gives the impression of white man’s imagination; it does not have the true ring of Indian tradition. Another account is that Tenaya (who was the chief of the Yosemite band at the time of the discovery and whose name is perpetuated in that of the canyon leading into the Valley) and his people lived in a country infested with bears. In addition, the band was reputed to consist of unusually fierce warriors. Therefore the sobriquet "Grizzlies" was bestowed upon them by the neighboring tribes. This story also does not seem wholly in accord with known principles of Indian nomenclature; although Dr. C. Hart Merriam says that the inhabitants of Hokokwila, the native village where the Sentinel Hotel now stands, were called "Yohamite," that is, "Ühümati" or Grizzly Bear. The true explanation of the name of the Valley is probably to be found in a peculiar social institution which the Yosemite Indians shared with the other Miwok.

This entire nation is everywhere divided into two groups or "moieties" or halves, as we might call them, which intermarry. The first social law of these Indians is that a man must always take to wife a woman from the other moiety. The children follow the father, and whether boys or girls are restricted in their choice of wife or husband to the second moiety, that of their mother. In this way the lineage is carried on uninterruptedly generation after generation.

These two intermarrying halves of the Miwok nation have the elements land and water as their designations or totems, and are known as Tunuka and Kikua. The division is made more picturesque by assigning every known species of animal and plant to one or the other division. Thus the bear and most land animals and birds belong to the land side. Fishes, water animals, and plants and a few exceptional ones from the land—especially the deer and coyote—are associated with water. In some parts of the Miwok country the people therefore speak of the "Blue Jay" and "Bullfrog" instead of the land and water divisions. In the Yosemite region it was customary to denominate the land side "Grizzly Bears" and the water side "Coyotes." Furthermore, within Yosemite Valley, all the villages on the north side of the Merced River were supposed to belong to the Grizzly Bear division, and those on the south the Coyote. It seems more than probable that this local name of one of these two sides or divisions came to be applied, through some misunderstanding on the part of the whites, to all the Indians of the valley, and then to the valley itself.

[Editor’s note: For the correct origin of the word Yosemite see “Origin of the Word Yosemite.”—DEA]

The points on the floor of Yosemite at which the Indians at one time or another lived or camped are numerous. Dr. C. Hart Merriam, the greatest living authority on these people, enumerates about forty such spots and supplies the information which he obtained about them and verified from the Indians. The principal sites are, in order down stream on the north side of the Merced and proceeding up stream again on the south side: Wiskala, at the foot of Royal Arches; Yowachki, near the mouth of Indian Canyon (this site is still occupied by a few families); Awani and Kumini, near Yosemite Falls, the former being the more important, in fact recognized as the largest and most permanent settlement in the Valley in aboriginal days; Hakaya, near the Three Brothers; Kisi and Chuchakala, opposite the last, on the south side of the river; Loya, at Sentinel Rock; Hokokwila, where the Sentinel Hotel now stands; Tuyuyuyu, near the Le Conte Memorial Lodge; and Omato, between Camp Curry and the Happy Isles.

It should be said, however, that these villages were preëminently summer encampments. Now and then a few families with an unusually favorable stock of supplies hoarded up, might remain in the valley from autumn to spring, but the majority of the inhabitants annually retreated to the canyon of the Merced River below El Portal in order to avoid the heavy snows of the 4000-foot altitude of Yosemite. Down below they waited, no doubt impatiently, for spring to come and permit them to resume occupation of the most favored of their hunting and food-gathering grounds. It may be added that the Indians, as their legends clearly indicate, were pretty fully aware of the extraordinary scenic features of the Valley, and derived much satisfaction from them; although with their native stolidity they no doubt expressed themselves less extravagantly than is the Caucasian habit.

The number of the band at the time of discovery is not accurately known, but may be estimated to have been in the vicinity of two hundred and fifty souls.

It was their raids on miners, prospectors, and scattered storekeepers, that in 1851 led to the formation of a little volunteer army known as Savage’s Mariposa Battalion. This company went up into the as yet unpenetrated mountains in pursuit of the Yosemite "Grizzlies" and to their overwhelming astonishment burst into the hitherto undiscovered valley. In the fighting that followed, the Indians were defeated, and part of them, including the Chief Tenaya, captured. The prisoners were taken to the San Joaquin Valley and put on a reservation. Here they kept the peace, but were in great distress of mind on account of their deprivation of the natural foods to which they were accustomed in their own haunts, as well as owing to their enforced contiguity to alien or hostile tribes. Tenaya pleaded to be let off. He was finally released, returned to Yosemite, and within four years was followed by all the surviving members of the band. The old chief did not long survive: he was killed by the Monos. He was not only a brave warrior but an unusual personality, who maintained his authority over his people by his native influence and by the respect which he commanded rather than by any legal position.

The Miwok social customs were numerous, and many of them strangely different from our own. The curious system of intermarrying divisions brought it about that a person always knew automatically to which moiety any given blood relative belonged. His father, his father’s father, his brothers and sisters, his children (if he were a man), his son’s children, and his uncles and aunts on the father’s side, were always of his own "side." His mother, her father, his wife, his father-in-law, his daughter-in law, and his daughter’s children, inevitably belonged to the opposite division. His mother’s mother, however, was always on his own side of the line-up. A woman differed from a man in that her children always belonged to the opposite division. Cousins were divided between the two sides according to whether the connection between them was through the male or the female line.

The dual totemic division was reflected in the personal names also. Any man, woman, or child, if his or her name referred to coyote or deer or beaver or otter or crane or salmon or salamander, or even indirectly alluded to these animals, was thereby designated as forming part of the water division. On the other hand, if his name had any reference to bear or wildcat or squirrel or raccoon or raven or a host of other animals he was a "landsman."

A curious custom was that while in general marriage with any blood relative, even of the seventh degree, was absolutely prohibited, an exception was made in favor of certain first cousins. Such cousins were in fact more or less expected to marry, if there was no satisfactory reason to the contrary. Which cousins were available for marriage, depended on the dual division principle. A man could never marry his father’s brother’s daughter, because the two brothers, and therefore their children, would belong to the same division. Cousins sprung from two sisters were also, ineligible, because, even though women did not transmit descent to their children, sisters were forced to mate with husbands of the opposite moiety; consequently their offspring would also be of the same descent and ineligible to one another. The daughter of one’s mother’s brother, however, was looked upon as one’s natural spouse. A simple calculation will show that such a cousin must always be of the opposite, division from oneself.

How this curious plan of relationships, marriages, and descent originated is unknown. The Miwoks themselves can give no explanation but take for

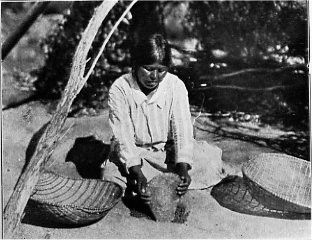

Miwok woman pounding acorns in bedrock mortar hole Photo by Univ. of Calif., Department of Anthropology |

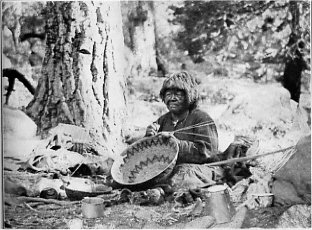

PLATE V Kalapine, an old Yosemite medicine woman, making a coiled basket. The process of manufacture, which is one of sewing, can be seen. Her hair is cut short in mourning Photo by J. T. Boysen |

The newly wedded man was expected to show deference to his wife’s parents by avoiding them as much as possible, especially the mother-in-law; and his wife behaved similarly toward his mother and father. The young people did not look their elders in the face or speak to them. If communication was necessary, the husband would address himself to his wife, and she in turn would repeat the statement to her mother, who would make the necessary answer by the same route, even though all three might be sitting in the same lodge. For a young man to do otherwise, would be the grossest breach of decorum, and the old lady would no doubt complain to her friends that her daughter seemed to have married a man lacking in all propriety and affection. This is another custom which the Indians assume is self-evident, and when asked for a reason they can give none except that they would be mortally ashamed to behave otherwise.

When a child is born, both father and mother have certain taboes imposed upon them. The man may not hunt nor do other than the necessary work, and both parent’s sit as quietly as possible about the house. After this follows a longer period during which they are free to resume normal occupations but must not eat certain kinds of food under penalty of injury to the health of the child.

The Miwok baby is put into a frame or "carrier," a sort of flat, hooded basket woven of slender sticks. In this it spends the greater part of the first twelve months of its life, and is easily carried about by the mother. The baby carrier has the further advantage of seeming to keep the infant still and contented. It is a notorious fact that Indian babies cry much less than white ones, and the native mothers declare that if they remove the children from their carriers the kicking about of legs and arms soon induces restlessness, discontent, and bawling. The woven hood of each of these tiny cradles is ornamented with a little pattern which differs according to sex. Zigzags or diagonal stripes show that the inmate is a boy, whereas a girl is indicated by a pattern of diamonds.

When a Miwok died, mourning and wailing were intense. His name must under no circumstances be spoken. To do so might invoke the ghost, and would in any event be considered as the deepest of all possible insults by his relatives. A widow cropped or burned her hair very short, smeared melted pitch over it, and also covered her face and breast with the same material. During the whole period of mourning she was not allowed to wash these parts of her body. After a few months of pitch and dirt, her appearance was a startling one: sufficiently forbidding, no doubt, to deter any prospective suitor. For the whole of the first year of her widowhood, also, she kept silence, or spoke only in low whispers to a female relative when the occasion was imperative.

Once a year, in each region of the Miwok country, usually in late summer or autumn, a great commemorative mourning ceremony for the dead was held, which lasted amid wailing and singing for several nights. Toward daybreak on the last morning immense accumulations of food and property were thrown into the fire by the mourners. Those of the deceased who had been of special rank, or particularly beloved by their survivors, were represented by rude effigies which were also consumed in the blaze. After this the mourners of the land side were ceremonially washed by the water people, and vice versa, to signify their cleansing from the period of grief and from the restrictions which they had been under. For the widow it was also a much needed literal cleansing.

When an Indian became sick, a shaman or medicine man was called in. This individual had acquired his power from spirits. He was believed to possess the power of clairvoyance. After dancing, singing, manipulating the patient, and other preliminaries, he would declare that the illness was due to the infraction of some religious taboo, or that some evil-minded medicine-man, a witch or wizard, had managed to lodge some foreign object or noxious little animal in the body of the sufferer.

He then proceeded to remove the poison by sucking the part affected, and finally pretended to remove a little mass of straw, a wisp of hair, a dead grasshopper or lizard, or something of that sort. The patient and his relatives of course felt immeasurably relieved, and, confidence having been regained, nature in most cases concluded the recovery.

If, however, the medicine-man was unfortunate and lost several patients, especially if these died in rapid succession, he paid dearly for his preëminence. The Indians were so convinced of the complete power of these shamans, that they gave them entire credit for every cure that happened. Consequently they were quite logical when they reasoned that the death of a patient must be due to the unwillingness or evil disposition of the practitioner. One or two fatalities might be pardoned as due to mere incompetence; but suspicion would be gathering, and after his third or fourth loss, the medicine-man’s life was worth little. The relatives of his deceased patients were simply waiting for an opportunity to ambush and murder him, and he must be a wary or powerful man indeed to escape permanently. Even to-day an occasional murder among the Sierra Nevada tribes can be traced to a lingering of this old custom.

The myths and legends of the Yosemite band rested on the same ideas as those current among the other Miwok. From these latter we gather that it was currently believed by the natives that this earth was peopled six successive times. The first world was dominated by a cannibal giant Uwulin who gradually devoured its inhabitants until little Fly discovered a tiny vulnerable spot in his heel—like that of Achilles—and despatched the malefactor. The people of the second world were not much better off, for they were stolen away by an immense bird, a sort of Roc, named Yelelkin, and the remainder were persecuted by ants until they were driven away. The third world was peopled by beings who were half human and half animal, and came to an end with their transformation into complete animals—a sort of retrograde evolution. The fourth race was vexed by its chief, Skunk, who kept for himself all meat, until his people succeeded in destroying him by strategy. In his death agonies Skunk upheaved the mountains. This race was also transformed into animals. As to the fifth world, tradition is obscure, but the sixth peopling was accomplished by Coyote. The earth was at this time covered with water, but Coyote had Frog dive and bring up a bit of soil from which he created land. He then caused vegetation to grow up and made human beings. He and his associates, who up to this time had been more or less human or even superhuman in attributes, then became changed into animals like those which we see to-day.

In the story of the origin of death among mankind, Coyote also figures. His plan was to have people covered up for four days and then arise reborn in the prime of manhood. For a while this arrangement worked to the satisfaction of everyone. Once, however, a person died just as Meadow-lark took to himself a wife. After a day or two, odors of decay began to arise from the blanket-covered pile and penetrated to the hut of the honeymoon couple. Meadow-lark resented having his bliss disturbed in this way, and proclaimed that a much, better plan would be to burn up the source of the stench and leave everyone in peace. His counsel prevailed and the first cremation took place, which the Miwok have adhered to ever since; but with it there passed away the habit of human lives being renewed over and over. Although they believe this tale, the Miwok seem to bear no resentment against Meadow-lark.

The greatest hero of Miwok legends is Wekwek, the Falcon, son of Condor or according to other versions of Yayil, and grandson of Coyote. Falcon fought and overcame a destructive giant, Kilak; escaped a fire that consumed the surface of the world; and underwent numberless other adventures. More than once he was killed and restored to life, and at other times he brought back among the living his father, his sister, or some friend. The Miwok never tire of telling about this character, who impersonates all that they conceive of daring and magic and skill in the days of long ago.

About Yosemite Valley proper there are a number of Indian stories which have repeatedly been recorded with but little variation, so that they may be considered authentic. The favorite one tells of a woman named Tiseyak who lived far down the Merced River, in or near the plains. Having quarreled with her husband, she ran away eastward, creating the course of the present stream and causing oak trees and other food-bearing plants to spring up along her route. In Yosemite Valley her husband overtook her and beat her soundly. In the scuffle, the hooded bady-cradle which she was carrying was thrown across to the north wall of the canyon, where the bent hood can still be seen in the Royal Arches. A globular basket which she had brought with her, landed bottom upward and became Basket or North Dome. The husband, who is known in the story as Nangas, "her husband," turned into North Dome or Washington Tower, whereas Tiseyak herself became Half Dome, the dark streaks on the sheer cliff of this great peak being the tears which her pain and humiliation had caused to stream down her face. The several versions vary in details, but in substance the tale is told by all the Yosemite Miwok as here outlined. It must be remembered that oral tradition can never be absolutely consistent in the mouths of separate individuals.

El Capitan, it is said, was originally a small rock. Once, long ago, a she-bear went to sleep on top with her two cubs. When they awoke in the morning, the rock had grown into the present tremendous cliff. Neither they nor the people of the village below knew how to rescue the unfortunates; until at last the Inch or Measuring Worm succeeded in humping his way up the cliff. By this time, however, the poor bear and her cubs had starved to death, and he could do no more than bring down their bones for cremation by their mourning relatives.

Measuring Worm was now possessed by the spirit of adventure. He reclimbed El Capitan, stretched himself clear across to the opposite side of the Valley, and drew himself over. Then he recrossed. This sport, however, must have weakened the walls of the canyon, for it was not long before they began to cave and the inhabitants were obliged to flee down the river in order to save themselves. The Indians say that before this catastrophe the Valley was even deeper than it is at present.

Waterfalls are dreaded by the Miwok, and both Yosemite and Bridalveil Falls are believed to be inhabited by spirits, those in the former being known as Poloti, and in the latter as Pohono. They cause gusts of wind which are likely to whirl into the falls people who venture too close. Once the Poloti captured a girl. She had gone to Yosemite Creek from Awani or a neighboring camp to bring back a basket of water. When she dipped up, it was full of snakes. These the spirits had caused to enter the vessel so that she might abandon her accustomed spot and move farther upstream. Each time she dipped her basket, the unfortunate girl found more vermin in it, and so gradually she went higher and higher up until she reached the pool at the foot of the falls, when a sudden violent gust blew her in.

It was with such tales as this that the Yosemite Indians used to beguile the long winter evenings while sitting about the fire.

Barrett, S. A., 1908. "The Geography and Dialects of the

Miwok Indians." Univ. of Calif. Publications in American

Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. vi., No. 2.

1919. "Myths of the Southern Sierra Miwok." Univ. of

Calif. Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology,

vol. xvi., No. 1.

Clark, Galen, 1904. Indians of Yosemite Valley and Vicinity., (Galen Clark, Yosemite) 110 pp., illus.

Gifford, E. W., 1916. "Miwok Moieties." Univ. of Calif.

Publ. in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. xii., No. 4

1917.

"Miwok Myths," Univ. of Calif. Publ. in American

Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. xii., No. 8.

Kroeber, A. L., 1916. "California Place Names of Indian Origin." Univ. of Calif. Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. xii., No. 2.

Merriam, C. Hart, 1910.

The Dawn of the World: Myths and

Weird Tales Told by the Mewan Indians of California.

(A. H. Clark Co., Cleveland), pp., illus.

1917.

"Indian Village and Camp Sites in Yosemite Valley."

Sierra Club Bulletin, vol. x., No. 2.

Powers, Stephen, 1877. "Tribes of California." Contributions to North American Ethnology, vol. iii.

Next: Ideals and Policy of the National Park Service • Contents • Previous: History of Yosemite

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/handbook_of_yosemite_national_park/indians.html