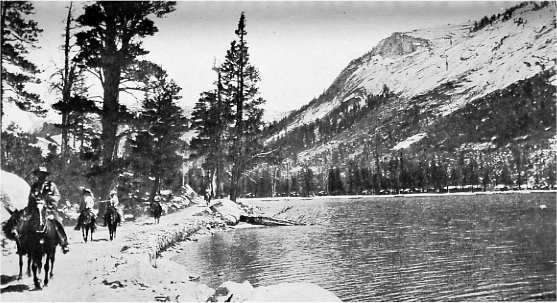

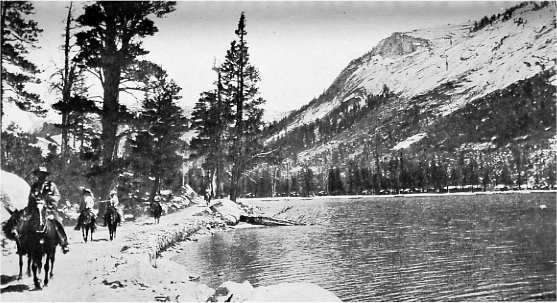

PLATE II

Tenaya Lake where the last remnant of the Yosemite tribe was captured by the Mariposa Battalion on June 5, 1851.

Photo by A. C. Pillsbury

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Handbook > History >

Next: Indians of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Illustrations

By Ralph S. Kuykendall

N. S. G. W., Fellow in Pacific Coast History,

University of California

It is probable that the first white men to look upon Yosemite Valley were members of the Joseph R. Walker expedition of 1833, which descended the western slope of the Sierra Nevada along the ridge between the Merced and the Tuolumne rivers. But the best contemporary evidence makes it clear that this party did not go down into the Valley. There are vague reports of hunters having entered the Valley as early as 1844, but the effective discovery of the Yosemite was made in 1851 by members of the Mariposa Battalion while in pursuit of hostile Indians.

When white men flocked into the foothills of the Sierra in search of gold it was not long before difficulties arose with the Indians. On this frontier was repeated the old story of the red man’s fight to keep possession of his ancestral home. The struggle was short, since the California Indians were not capable of maintaining a long contest. In this connection we are concerned with only that part of the struggle which is known as the Mariposa Indian War.

In the beginning of 1850, James D. Savage had a trading post and mining camp on the Merced River some twenty miles below Yosemite Valley, which was at that time unknown to the whites. During the spring of that year Indians came down the river and made an attack on this post. They were driven off, but Savage thought it best to abandon the place and remove his store to Mariposa Creek. He also established a branch post on the Fresno River and at both places built up a prosperous trade. Savage had several Indian wives and obtained quite a remarkable influence over the tribes with which he was connected. But there were malcontents among them and the tribes in the mountains were suspicious and easily incited to acts of hostility.

On December 17, 1850, Savage’s Indians deserted the Mariposa camp and on the same or the following day his post on the Fresno was attacked and two of the three men there present were killed. Adam Johnston, the Indian agent, visited the place two days later and describes it as "a horrid scene of savage cruelty. The Indians had destroyed everything they could not use, or carry with them. The store was stripped of blankets, clothing, flour, and everything of value; the safe was broken open and rifled of its contents; the cattle, horses, and mules had been run into the mountains; the murdered men had been stripped of their clothing and lay before us filled with arrows; one of them had yet 20 perfect arrows sticking in him." Several similar outrages occurred soon after and signalized the beginning of a general Indian war.

Under these circumstances the white settlers took prompt action to protect themselves. Under the lead of Sheriff James Burney and James D. Savage, a volunteer company was formed, January 6, 1851, with Burney in command. This force had several indecisive skirmishes with the Indians. Meanwhile the governor was appealed to and he at once authorized Sheriff Burney to call out two hundred militiamen and organize a battalion for service as the emergency might demand. Under this authorization the Mariposa Battalion was formed February 10th, at Savage’s partially ruined store on Mariposa Creek. Savage was elected major, and three companies were organized under command of Captains John J. Kuykendall, John Bowling, and William Dill. Headquarters were established on Mariposa Creek and here the battalion was drilled in preparation for the campaign, and occasional scouting forays were made into the enemy’s country.

About this time the United States Indian Commissioners, McKee, Barbour, and Wozencraft arrived in California with instructions to make treaties with the Indian tribes. It was agreed that the commissioners would go at once to the disaffected region and endeavor to treat with the hostile tribes, and that the volunteer battalion which had been raised should be subject to their directions. If negotiations failed, force would be used to bring the Indians to terms. The commissioners arrived at the Mariposa camp about the first of March, and immediately sent out runners inviting the various tribes to come in and have a talk. A meeting was arranged for the ninth of arch, and on the nineteenth a treaty was made with six tribes, which were at once removed to a reservation between the Merced and the Tuolumne rivers. The commissioners then went on to talk with the tribes south of the Merced River, and left part of the volunteer battalion to deal with the Indians who had refused to enter into the treaty.

Among these were the Yosemites, and reports brought in by friendly Indians indicated that they had no intention of coming in to make peace. It was therefore deemed necessary to send a military force after them.

On the evening of March nineteenth, the very day on which the treaty was signed, Major Savage set out with the companies of Captains Bowling and Dill. "The march was over rugged mountains and through deep defiles covered with snows and was one of considerable exposure and hardship. . . . Part of the march was exceedingly difficult and dangerous. It lay along a deep canyon and a part of it had to be made through the water and a part over precipitous cliffs covered with snow and ice."

On the morning of the twenty-second, a Nuchu rancheria, on the South Fork of the Merced River was surprised and captured without a fight. At this point a camp was established and messengers were sent ahead to the Yosemites with a request that they come into camp. Next day the old Chief Tenaya came in alone, and after an interview with Savage promised that if allowed to return to his people he would bring them in. Part of the tribe came in and Tenaya was sent with them to the camp on the South Fork.

In order to round up the remainder, Savage took one of the young braves as a guide and continued his march toward the north. Within a short time the company came to old Inspiration Point and the full view of the Valley was presented to their gaze. It must be confessed, however, that the scenic wonder of this valley made a very slight impression on these rough men of action, and without much ado they hastened down the trail and camped for the night on the south side of the Merced River, a little below El Capitan. The day of the discovery was March 25, 1851.

As the tired campaigners sat about the camp fire that night the events of the day were passed in review and the question arose of giving a name to the valley which they had found. Dr. L. H. Bunnell, upon whom the scenes and events of this campaign made a deeper impression than upon any of the others, suggested the appropriateness of naming it after the aborigines who dwelt there. The suggestion was greed to after some good-natured banter, and since the white men called these Indians Yosemites the name Yosemite was given to the Valley

The next day was spent in a search of the Valley, but no Indians were found save an ancient squaw who was too old and decrepit to make her escape. Indian huts, evidently deserted but a few hours before, and large caches of acorns and other provisions were found and destroyed. The Valley was thoroughly explored by the volunteers, one party going up Tenaya Creek beyond Mirror Lake and another ascending the Merced to a point above Nevada Fall. The search proving fruitless and the supplies running low it was decided to abandon the chase and return to the camp on the South Fork. From there the Indians who had been gathered together were started toward the commissioners on the Fresno, but before they arrived at their destination the negligence of the guard permitted them to escape and they returned to their mountain fastnesses.

Early in May, Captain Bowling and his men were sent out a second time in pursuit of the Yosemites. His orders from Major Savage were to "surprise them and whip them well," and in case that proved impossible then to use any means in his power to induce them to come down and treat. The following account of this expedition is quoted from Captain Bowling’s report in the form of two letters, one of which is beyond any question the first letter ever written in the Yosemite Valley. Writing from the "Yo-Semety Village, May 15, 1851," he says1: [1 The following authentic account was recently found by the author in the San Francisco Alta California for June 12 and 14, 1851, and differs in some details from the narratives presented in Bunnell’s Discovery of the Yosemite and Hutchings’ In the Heart of the Sierras. Editor’s note.]

"On reaching this valley, which we did on the 9th instant, I selected for our encampment the most secluded place that I could find, lest our arrival might be discovered by the Indians. Spies were immediately dispatched in different directions, some of which crossed the river to examine for signs on the opposite side. Trails were soon found, leading up and down the river, which had been made since the last rain. On the morning of the 10th we took up the line of march for the upper end of the valley, and having traveled about 5 miles we discovered five Indians running up the river on the north side. All of my companions, except a sufficient number to take care of the pack animals, put spurs to their animals, swam the river and caught them before they. could get into the mountains. One of them proved to be the son the old Yosemite chief. I informed them that if they would come down from the mountains and go with me to the United States Indian commissioners, they would not be hurt; but if they would not, I would remain in their neighborhood as long as there was a fresh track to be found; informing him at the same time that all the Indians except his father’s people and the Chouchillas had treated. . . . He then informed me that . . . if I would let him loose with another Indian, he would bring in his father and all his people by twelve o’clock the next day.

"I then gave them plenty to eat and started him and his companion out. We watched the others close, intending to hold them as hostages until the dispatch-bearers returned. They appeared well satisfied and we were not suspicious of them, in consequence of which one of them escaped. We commenced searching for him, which alarmed the other two still in custody, and they attempted to make their escape. The boys took after them and, finding they could not catch them, fired and killed them both. This circumstance, connected with the fact of the two whom we had sent out not returning, satisfied me that they had no intention of coming in. My command then set out to search for the rancheria. The party which went up the left toward Canyarthia [?] found the rancheria at the head of a little valley, and from the signs it appeared that the Indians had left but a few minutes. The boys pursued them up the mountain on the north side of the river, and when they had got near the top, helping each other from rock to rock on account of the abruptness of the mountains, the first intimation they had of the Indians being near was a shower of huge rocks which came tumbling down the mountain, threatening instant destruction. Several of the men were knocked down, and some of them rolled and fell some distance before. they could recover, wounding and bruising them generally. One man’s gun was knocked out of his hand and fell 70 feet before it stopped, whilst another man’s hat was knocked off his head without hurting him. The men immediately took shelter behind large rocks, from which they could get an occasional shot, which soon forced the Indians to retreat, and by pressing them close they caught the old Yosemite Chief, whom we yet hold as a prisoner. In this skirmish they killed one Indian and wounded several others.

"You are aware that I know this old fellow well enough to look out well for him, lest by some stratagem he makes his escape. I shall aim to use him to the best advantage in pursuing his people. I send down a few of my command with the pack animals for provisions; and I am satisfied if you will send me 10 or 12 of old Ponwatchi’s best men I could catch the women and children and thereby force the men to come in. The Indians I have with me have acted in good faith and agree with me in this opinion." The account is continued in the second letter which was written May 29th at the camp on the Fresno River:

". . . Notwithstanding the number of our party being reduced to 22 men, by the absence of the detachment necessary to escort with safety the pack train, we continued the chase with such rapidity, that we forced a large portion of the Indians to take refuge in the plains with the friendly Indians, while the remainder sought to conceal themselves among the rugged cliffs in the snowy region of the Sierra Nevada.

"Thus far I have made it a point to give as little alarm as possible. After capturing some of them I set a portion at liberty, in order that they might assure the others that if they come in they would not be harmed. Notwithstanding the treachery of the old chief, who contrived to lie and deceive us all the time, his grey hairs saved the boys from inflicting on him that justice which would have been administered under other circumstances. Having become satisfied that we could not persuade him to come in, I determined on hunting them, and if possible running them down, lest by leaving them in the mountains they would form a new settlement and a place of refuge for other ill-disposed Indians who might do mischief and retreat to the mountains, and finally entice off those who are quiet and settled in the reserve. On the 20th [of May] the train of pack animals and provisions arrived, accompanied by a few more men than the party which went out after provisions, and Ponwatchi, the chief of the Nuchtucs, [Nuchu] tribe with 12 of his warriors.

"On the morning of the 21st we discovered the trail of a small party of Indians traveling in the direction of the Monos’ country. We followed this trail until 2 o’clock next day, 22d, when one of the scouting parties reported a rancheria near at hand. Almost at the same instant a spy was discovered watching our movements. We made chase after him immediately and succeeded in catching him before he arrived at the rancheria, and we also succeeded in surrounding the ranch and capturing the whole of them. This chase in reality was not that source of amusement which it should seem to be when anticipated. Each man in the chase was stripped to his drawers, in which situation all hands ran at full speed at least four miles, some portion of the time over and through snow ten feet deep, and in this four-mile heat all Ponwatchi gained on my boys was only distance enough to enable them to surround the rancheria while my men ran up in front. Two Indians strung their bows and seized their arrows, when they were told if they did not surrender they would be instantly killed.

"They took the proper view of this precaution and immediately surrendered. The inquiry was made of those unfortunate people if they were then satisfied to go with us; their reply was they were more than willing, as they could go to no other place. From all we could see and learn from those people we were then on the main range of the Sierra Nevada. The snow was in many places more than 10 feet deep, and generally where it was deep the crust was sufficiently strong to bear a man’s weight, which facilitated our traveling very much. Here there was a large lake completely frozen over, which had evidently not yet felt the influence of the spring season.1 [1 This was Tenaya Lake, named after the old chief. ] The trail which we were bound to travel lay along the side of a steep mountain so slippery that it was difficult to get along barefoot without slipping and falling hundreds of yards. This place appearing to be their last resort or place where they considered themselves perfectly secure from the intrusion of the white man. In fact those people appear to look upon this place as their last home, composed of nature’s own materials, unaided by the skill of man.

"The conduct of Ponwatchi and his warriors during this expedition entitled him and them to much credit. They performed important service voluntarily and cheerfully, making themselves generally useful, particularly in catching the scattered Indians after surprising a rancheria. of the Yosemites, few, if any, are now left in the mountains. . . .

"It seems that their determined obstinacy is entirely attributable to the influence of their chief, whom we have a prisoner, among others of his tribe, and whom we intend to take care of. They have now been taught the double lesson—that the white man would not give up the chase without the game, and at the same time if they would come down from the mountains and behave themselves they would be kindly treated.

Altogether Captain Bowling’s command spent about two weeks in the Valley on this occasion. The main purpose of the expedition having been accomplished, a return was made to the headquarters on the Fresno and the Indians were placed on the reservation. Tenaya, however, chafed under restraint and appealed repeatedly for permission to return to the mountains. Finally, on his solemn promise to behave, he was allowed to go back to the Valley, taking his immediate family with him. In a short time a number of his old followers made their escape from the reservation and were supposed to have joined him. No attempt was made to bring them back, and no complaint was heard against the Yosemites during the winter of 1851-52.

On the 20th of May, 1852, a party of eight prospectors started from Coarse Gold Gulch on a trip to the upper waters of the Merced River. They had just entered the Yosemite Valley when they were set upon, by a band of Indians and two of them, named Rose and Shurborn, were killed and a third badly wounded. The others got away and after enduring great hardships arrived again at Coarse Gold Gulch on the 2d of June. The same day about thirty or forty miners set out to punish the treacherous Yosemites. This party found the bodies of the murdered men and buried them at the edge of Bridalveil Meadow, where their graves are still to be seen, but they were compelled to return without punishing the murderers.

The commander at Fort Miller being informed of these events, a detachment of Regulars under Lieutenant Moore was at once dispatched into the mountains. On arriving in the Yosemite Valley this expedition surprised and captured five Indians. Clothing said to belong to the murdered men being found upon them, they were summarily shot. The remainder of the Yosemites with their old Chief Tenaya made their escape and fled over the mountains into the Mono country. Thither the soldiers pursued, but were unable to catch any of them. The party lost a few horses, killed by the Indians, explored the region about Mono Lake, discovered some gold deposits, and then returned to the fort on the San Joaquin by a route that led south of the Yosemite Valley. A diary of this expedition, published in one of the Stockton newspapers about the 1st of October, 1852, contains one of our earliest descriptions of Mono Lake and vicinity. After the return of the expedition, a party of miners under the leadership of Leroy Vining, attracted by the reported gold discoveries, crossed over the mountains and established themselves on what came to be known as Vining’s Gulch or Creek. (The name appears on the maps a little later as Lee Vining Creek and upon the present maps as Leevining Creek.)

Tenaya and his fellow tribesmen seem to have remained among the Monos until the summer of 1853, when they returned once more to Yosemite Valley. They repaid the hospitality of the Monos by stealing a number of their horses. This proceeding stirred the wrath of the Monos, and they determined to wreak vengeance upon their erstwhile guests. They put on their war paint and descended suddenly upon the Yosemites while the latter were in the midst of a gluttonous feast. Old Tenaya had his skull crushed by a rock hurled from the hand of a Mono warrior and all except a handful of his followers were slain. The tribe was virtually exterminated, though a few of their descendants still survive.

In spite of the exciting events which have been related above, Yosemite Valley was little disturbed by the visits of white men for some years longer. The Californians of that day, and particularly those in the mining region, were on the whole very little interested in scenery. Early in 1855, however, one of the very meager descriptions of the Valley which had found its way into print came by chance to the notice of J. M. Hutchings. Hutchings was at the moment laying plans for the publication of his California Magazine, and for that reason the mention of a waterfall a thousand feet high arrested his attention, and he resolved to investigate the matter.

Early in the summer Hutchings organized what may fairly be considered the first tourist party to visit the Yosemite, consisting of himself, Walter Millard, and Thomas Ayres, an artist. At Mariposa, a fourth member, Alexander Stair, joined the party. Some difficulty was experienced in the matter of a guide, but finally, through the assistance of Captain Bowling and some other members of the Mariposa Battalion, two Indians were found to perform that essential service, and in due time the party found their way into the Valley, where they spent, says Hutchings, "five glorious days in luxurious scenic banqueting." Upon their return to the settlements these men gave an enthusiastic account of their experiences. Hutchings wrote an article which was printed in the Mariposa Gazette of August 16th, and parts of which were quoted in the San Francisco California Chronicle of August 18th. A picture drawn by Ayres was lithographed and published soon after, and before the year was out two other parties made their way into the Valley In the same year the construction of the first trail into the Valley was begun by Milton and Houston Mann. It was completed the next year but did not prove a paying investment and was soon sold to the county of Mariposa and made free. The old Coulterville trail was opened within a year or two and the Valley thus made accessible. from both north and south; but accessible by rather a hard and painful journey. As time went by roads approached ever

PLATE II Tenaya Lake where the last remnant of the Yosemite tribe was captured by the Mariposa Battalion on June 5, 1851. Photo by A. C. Pillsbury |

In 1855 the walls of a cabin were erected in the lower end of the Valley by a party of surveyors who were seeking water for the Mariposa dry diggings, but the first house actually completed was built in 1856-1857. Being severely damaged by snow, it was replaced in 1858 by a more substantial structure, which was kept as a hotel during the next decade by a number of different parties. Included in the number of these early Yosemite inn-keepers was the Longhurst whom Clarence King describes as a "weather-beaten round-the-worlder, whose function .. . . was to tell yarns, sing songs, and feed the inner man," and whose flapjacks the same fascinating writer professed a reluctance to eat, because that would seem like "breakfasting in sacrilege upon works of art." In 1859 was completed the central portion of the building which later became known as the Hutchings House, the lumber all being hewed or sawed out by hand. It may be of interest to note that this building (the present Cedar Cottage) was the subject of the first photograph ever taken in Yosemite. [Editor’s note: Charles Leander Weed’s first photograph, taken June 18, 1859 was of Yosemite Falls, not what was latter known as the Hutchings House, which was photographed 3 days later—dea.]

The first permanent resident in the Valley was James C. Lamon, who took up a preëmption claim in its upper end in the fall of 1859, built a cabin, and laid out a garden and orchard which became famous in after years. From 1862 he resided in the Valley both summer and winter until his death in 1876.

In the spring of 1864 J. M. Hutchings came to Yosemite with his family, having purchased a claim and arranged to buy the building to which his name became attached. After his advent as a permanent resident Hutchings was for a decade the leading figure in the Valley’s history. He was "mine host" to a large proportion of the people who visited Yosemite in that period, and while there is abundant evidence that as an hotel-keeper he was not an overwhelming success, we may, perhaps, assume that his hospitable enthusiasm compensated in some degree at least for the defects of his hostelry.

In order to make necessary improvements in his establishment Hutchings erected a small sawmill near the Yosemite Fall, for the purpose of turning into lumber a lot of trees that had been thrown down by a windstorm some years before. This sawmill of Hutchings’ has rather a higher claim to notice than is possessed by most such structures: for nearly two years it was operated by no less a personage than John Muir. Muir was then on the threshold of his career, engaged, in the intervals between his work as sawyer and guide, in gathering the data on which were based his glacial studies of the high Sierra and in forming that passionate attachment for the "Mountains of Light," which proved to be so significant a factor in his life as well as in the history of the region.

It was also the scene of the first meeting, in August, 1870, of two men whose names and memories will forever linger in these mountains—Muir and the elder Le Conte. The latter has described the meeting and set down his first impressions of Muir:

"To-day to Yosemite Falls. . . . Stopped a moment at the foot of the falls, at a sawmill, to make inquiries. Here found a man in rough miller’s garb, whose intelligent face and earnest, clear blue eye, excited my interest. After some conversation discovered that it was Mr. Muir, a gentleman of whom I had heard much from Mrs. Prof. Carr and others. He had also received a letter from Mrs. Carr, concerning our party, and was looking for us. . . . I urged him to go with us to Mono. [Later in the day we] learned from Mr. Muir that he would certainly go to Mono with us. We were much delighted to hear this. Mr. Muir is a gentleman of rare intelligence. . . . He has lived several years in the Valley, and is thoroughly acquainted with the mountains in the vicinity. A man of so much intelligence tending a sawmill!—not for himself, but for Mr. Hutchings. This is California!"

It seems singularly appropriate that these two men should meet thus for the first time in the great temple of nature which both loved so well; and under such circumstances, Muir in the rough garb of a mill operator and Le Conte in the scarcely less rough garb of a mountain traveler. It was Le Conte’s first summer in the Sierra, and Muir conducted him and his party over the route which he himself had traced out for the first time only a year before.

During the first decade after the Valley was brought to general notice the desirability of setting it aside as a park became manifest. The danger that it would soon fall into private hands led Senator Conness of California, in 1864, to secure the passage by Congress of an act granting to the State of California "the Cleft, or Gorge, in the Granite Peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains . . . known as the Yosemite Valley," with the stipulation, however, that it should be held for public use, resort, and recreation and should be inalienable for all time.

By the same act the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, four square miles, was also granted to the State under the same conditions. The act further provided that the two grants should be managed by a board of commissioners consisting of the Governor and eight other persons appointed by him.

On September twenty-eighth Governor F. K. Low issued a proclamation naming Frederick Law Olmsted, Professor Josiah Dwight Whitney, William Ashburner, I. W. Raymond, E. S. Holden, Alexander Deering, George W. Coulter, and Galen Clark as commissioners, and warning all persons to desist from trespassing or settling upon either of the two grants. At the first session of the legislature thereafter a law was enacted, April 2, 1866, legally constituting the Board of Commissioners, making the necessary provisions for the control and administration of the trust created by the grant from the federal government, and making a small appropriation for the first two years.

The commissioners first named and those subsequently appointed were, as a whole, well selected, but circumstances conspired to defeat many of their best efforts. They had scarcely entered upon the discharge of their duties when they found themselves involved in a prolonged litigation. The settlers, Hutchings and Lamon, who had made their homes in the Valley, refused to surrender their holdings upon the invitation of the Commission. After some fruitless negotiation a test suit was brought against Hutchings, which in the district court was decided in his favor. On appeal to the Supreme Court of the State the judgment was reversed, and on being carried to the federal Supreme Court the position of the Commissioners was fully sustained. But in the meantime Lamon and Hutchings had brought their case to the legislature, and that body, under the influence of a sympathetic agitation, passed a bill granting to each of them a tract of 160 acres in the Valley, subject, however, to the approval of Congress. That approval was never given, so that finally, in 1875, after a second legal action against Hutchings, the Commissioners found themselves in full and undisputed control, for the State, of the property which they had been appointed to manage. On their recommendation the legislature in 1874 appropriated $60,000 to compensate Lamon, Hutchings, and two others for the loss of their claims in the Valley.

The Commissioners were unquestionably right in the position which they assumed, and we cannot dismiss this phase of the subject without remarking upon the service which they rendered to the State and the nation in thus pursuing the case to its final settlement in their favor. The extinguishment of private titles has been one of the most perplexing and difficult problems confronting the administration of the park, whether state or national. At the same time we cannot overlook the equities in the case of the settlers, nor forget the fact that Hutchings in this early period did more perhaps than any other one person to make known to the world the beauties and the wonders of Yosemite.

This controversy resulted in the creation of a rallying point for all forces hostile to the park administration. The granting of a road privilege on the north side of the Valley furnishes another example of the difficulties constantly arising. In 1869 the Commissioners granted to certain parties interested in the Big Oak Flat route the exclusive privilege of extending a toll road to the floor of the Valley on that side. These parties having failed to carry out their agreement, the Commissioners in 1872 granted a similar exclusive privilege to the Coulterville and Yosemite Turnpike Company, who went to work at once and completed their road into the Valley June 17, 1874. After this privilege had been granted, the Yosemite Turnpike Road Company, representing the Big Oak Flat route, applied for the privilege of building a free road from the edge of the park into the Valley. This, being denied by the Commission, the company appealed to the legislature, which gave it the right prayed for. This road also was completed in the summer of 1874, and in the following year the Wawona road was extended into the Valley.

The Commissioners were greatly handicapped by the litigation described and the hostility which it engendered; by the action of the legislature in overriding their decisions, in the cases above mentioned; by the fact that the public was generally indifferent except as it was aroused by the distressed appeals of adversely affected individuals; by the lack of funds with which to work; and to an important degree by the fact that there was no accepted park practice or policy to guide them. Opposition to the Commission culminated in the legislative session of 1880, when the Commissioners were incontinently ousted from office by the action of the legislators and a subsequent decision of the Supreme Court of the State. A new law was passed and a new board appointed.

The new body signalized its entry into office by appointing as Guardian J. M. Hutchings, in place of Galen Clark who had held the office for the preceding fourteen years. This board profited to some extent by the experience of its predecessor, especially since the controversy over private holdings had been settled, but it also succeeded in doing many things which called forth sharp criticism. It was necessary to adopt a policy for dealing with such questions as the granting of hotel, carriage, and saddle-train privileges, the use that should be made of the meadow lands, and the kind of attention that should be given to the wooded areas—whether to cut and prune or to leave the brush and young trees to grow untouched; and the policy adopted was sure to displease someone.

Still, the new Commission was in much better position to do effective work than the old one had been, and the next decade saw important results accomplished—the roads and trails within the park lines were freed from the vexatious tolls that had before encumbered them; new roads and bridges were constructed within both the Yosemite grant and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove; a pretentious hotel, the Stoneman House, was erected near the upper end of the Valley, for which the legislature in 1885 appropriated $40,000. The new hotel turned out to be an unprofitable investment, for, as it was not properly constructed, expensive repairs were necessary. The building was finally burned to the ground in the summer of 1896.

The remainder of the period during which Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove remained under state control witnessed slow but steady development along all lines; and it also witnessed a more significant thing—the growth of a wider and more intelligent interest in matters affecting the park, which had an inevitable and healthy reaction upon the administration.

It is only in recent years that the vast alpine region to the north and east of Yosemite Valley has become generally known to tourists, though for many years before that it was familiar to many mountain lovers. The first white men who frequented this Yosemite hinterland were miners and sheepherders and cattlemen. After them came the surveyors and then the soldiers of the republic to guard the mountain meadows and forests from the destructive forces at work. And lastly the tourists, at first in little groups at long intervals, but now in throngs, to see the glories of the mountains.

The first systematic reconnaissance of the Yosemite region was made by the California Geological Survey between 1863 and 1867. The first expedition, in 1863, covered in a general way the watershed between the Merced and the Tuolumne and the headwaters of those rivers. Their later expeditions were made directly as a result of the creation of the state park, first to survey its boundaries and secondly to gather data or the preparation of the maps and text of a book descriptive of the Yosemite region which was published by the California Geological Survey in 1868. It was in connection with these and other expeditions of the State Geological Survey that Clarence King had the experiences so delightfully described in his book "Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada." To this survey we are indebted for the names of many of the peaks, and for the first accurate maps of the region. The same area was covered in 1878-79 by a party of the Wheeler Survey in charge of Lieutenant M. M. Macomb. The definitive mapping of the region has, of course, been done by the United States Geological Survey, whose fine topographic maps are familiar to all mountain travelers.

The trail of the miner is found everywhere in the Sierra Nevada. We have already seen that the discovery of Yosemite was a result of the mining advance into the foothills. Subsequently there were two well defined periods of mining excitement which were of importance in the history of the region. The first of these began about 1857 when placer gold was discovered in what are broadly referred to as the Mono diggings. To accommodate the miners and pack trains passing to and fro across the range the Mono Trail was blazed out easterly along the ridge between the Merced and the Tuolumne, following in the main old Indian trails, and descending into the Mono plain through the steep defile of Bloody Canyon. For a few years this trail was much traveled and then fell into disuse as the placers were worked out. When Joseph Le Conte passed over it first in 1870 he found it nearly obliterated in many places.

The miners went elsewhere, but soon flocked back again in even greater numbers, when gold and silver ores were discovered in the summit ridge about 1878. In a short time claims were staked out all the way from Parker Pass to Virginia Creek, but the interest centered principally at Lundy and Tioga. In 1881 a group of Eastern capitalists incorporated the Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Mining Company for the purpose of exploiting the central group of claims in the Tioga District. A post office, called Bennettville in honor of the president of the company, was established and operations were vigorously pushed. The writer has seen in a little paper published at Lundy a graphic description of the way in which the first machinery for the Tioga mine was snaked up the mountain side to Oneida Lake on skids, hoisted with a windlass to the summit of Tioga crest and thence dragged past Saddlebag Lake into Tioga in the dead of winter.

But this was too primitive a method to be used for bringing in all the heavy machinery and other supplies required. The company therefore determined to build a road up the western slope to Bennettville; and thus was inaugurated the building of the famous Tioga Road. The surveys were made in 1882 and construction work was begun in the fall of that year, Chinese labor being employed. The road was completed in the fall of 1883, having cost about $62,000. In December, 1883, and January, 1884, toll franchises were granted by the counties of Mariposa and Tuolumne and for a short time tolls were collected from travelers who used the road.

Financial disaster overtook the company after it had expended over $300,000 and the mine was closed in July, 1884. Subsequently, in January, 1888, he entire property, including the road, was sold by the Sheriff to W. C. N. Swift of New Bedford, Mass., who had been interested in the original company. In 1889 operations were resumed in the mine but were not long continued. The road, abandoned by its owners, year by year fell into disrepair.

It was during this period of mining excitement that John L. Murphy took up his claim on the shore of Lake Tenaya, built a cabin, and established a stopping place that was sometimes distinguished with the title of hotel. John B. Lembert took up a claim in the Tuolumne Meadows which included the Soda Springs. For several years a saddle train was run during the summer between Lundy and Yosemite, and these places were connected by telephone. There was also the inevitable crop of rumors regarding projected railroads to cross the Sierras through this region. Finally it is to be noticed that in the summer of 1881 silver mineral was discovered near Mt. Hoffman and the considerable excitement occasioned by it resulted in the organization of the Mt. Hoffman Mining District. Some months later John B. Lembert is said to have found a vein of silver bearing quartz in the Tuolumne Meadows. Sufficient quantities of ore have never been found to justify the working of these claims.

During all this time the Yosemite region was the haunt of the sheepherders and their all-devouring woolly charges. The mountain meadows are the finest of all sheep pastures, and year by year they were visited by countless thousands of these "hoofed locusts," as John Muir aptly termed them. As soon as the early summer heat dried up the grasses of the plains and foothills the herds were headed toward the higher mountains, and before the autumn chill started them on their backward journey to the plains they had penetrated into every little grassy glade, leaving a desert in their wake, eating up or trampling to death every young plant that lay in their path, not excepting the young fir, which were for them an especially prized tidbit.

John Muir in his first summer in the Sierra noted the damage and destruction that was wrought by the sheep. The State Engineer, Wm. Ham Hall, in a report to the State Commission in 1882, called attention to the disaster threatening the Valley from the indiscriminate grazing of sheep in the Merced watershed. It was not alone the fact that the sheep ate up every green thing within their reach, or that their myriad trampling feet loosened the soil on the hillsides; the shepherd, through design or carelessness, applied the match, and "his trail to the plain was marked by the smoke of the burning forest."

The sheep may fairly be said to have been responsible for the formation of the Yosemite National Park. The first determined effort to protect the region surrounding the Valley from the destruction wrought by them was in 1881, when the State Commissioners fathered a movement to include in the state park a district somewhat smaller than the present national park. A bill embodying this plan was introduced into Congress but through the vigorous opposition of powerful local interests the success of the movement was frustrated. The Commissioners continued for some years to urge the measure, but they were never able to muster sufficient influence to put it through.

In 1889, John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson, one of the editors of the Century Magazine, camped together in Tuolumne Meadows. Muir pointed out to his friend the devastation that was being wrought by the sheep, and it was agreed, at Johnson’s suggestion, that the way to save the region was to have it set aside as a national park. A plan of action was agreed upon—Muir to write for the Century a series of articles designed to arouse public sentiment, and Johnson to secure for the movement as much support as possible from influential men in the East. The movement thus launched culminated successfully in the enactment of a law, approved October 1, 1890, to set aside this region as "reserved forest lands." The name Yosemite National Park was somewhat inconsistently applied to it by the Secretary of the Interior. The original boundaries were larger !an the present limits of the Park, including as they Id a considerable area on the west and southeast which has been eliminated by subsequent legislation.

The control of the Park was vested in the Secretary of the Interior, and the plan of administration adopted was to place the local authority in the hands of an Acting Superintendent, who was a military officer in charge of one or more troops of cavalry. The first Superintendent was Captain A. E. Wood, an intelligent and energetic officer, for whom the post at Wawona was later named. The soldiers ordinarily came in in April or May and took their departure in October. During the winter two forest rangers patrolled the Park, so far as it could be patrolled.

The difficulties confronting the first Superintendent were rather formidable: the boundaries not having been surveyed were difficult or impossible to locate; the country to be patrolled was large and extremely rough; there was no well-planned trail system, and no detailed topographic map showing the location of such trails as did exist; it was necessary for the Superintendent to make himself acquainted with the region and to organize and direct a plan for protecting it, from the encroachments of the sheep and cattlemen, who, having had undisturbed use of the Park for a quarter of a century, were extremely reluctant now to abandon it.

Headquarters were established at Wawona and from there patrols were sent out to cover the entire Park systematically. The principal work of these patrols was in fighting fires and in preventing trespassing within the Park lines by sheep and cattle. No penalty had been provided by Congress for the infraction of rules. The army officers ingeniously adopted the plan of driving the sheep from the Park and escorting the herders across the mountains to the opposite boundary. This plan when vigorously followed soon resulted in reducing this evil to a minimum. Besides these more general duties the soldiers frequently were compelled to repair trails and bridges along the line of their march. One Superintendent reports the clearing out and repair by the troop of more than sixty miles of trails in one season. The protection of the game within the Park from the depredations of predatory hunters was an important duty of the patrols.

These troopers were faithful and efficient. In the discharge of their duties they not infrequently were called upon to push their way through snow-filled passes and to ford bowlder strewn and angry mountain streams at flood water, sometimes in peril of their lives. One carries away from a perusal of the reports of the various Superintendents an increased respect for the military arm of the national government.

To the subordinate officers of the command there were frequent opportunities for special service. During the early years Lieutenants N. F. McClure, H. C. Benson, M. F. Davis, and W. R. Smedberg made a careful study of the topography of the region and from their notes and the results of previous surveys Lieutenant McClure prepared an excellent map for the use of the troops, on which the topography and the trails were accurately delineated. Lieutenant Benson spent several seasons in the Park, first as a junior officer and later with rank of Captain and Major as Acting Superintendent, and has always been keenly interested in all matters affecting it. It was upon his suggestion that the system of permanent patrolling stations was instituted in 1903. This greatly facilitated the work of the troopers. After a few years a telephone line was built connecting these stations with headquarters in Yosemite Valley, and thus instant communication could be had with all parts of the Park.

Lieutenant Benson was an enthusiast on the subject of fishing and at all times took a lively interest in the stocking of the waters of the Park. Not only did he direct the planting of trout fry sent into the Park by the California State Fish Commissioners, but he personally netted trout in a number of lakes and streams and placed them in unstocked waters.

This was a work of primary importance, since fish are not indigenous in any of the lakes or streams in the upper Yosemite region. John L. Murphy is said to have planted trout in Tenaya Lake in 1878, and about the same time the Yosemite State Commissioners took up the question of stocking the Yosemite streams. They proposed to have a hatchery established in the Valley. This plan, renewed from time to time, was not then carried out, but at their suggestion the State Fish Commissioners sent in young trout to be planted in the Merced River and its tributaries. After the establishment of the national park the planting of trout fry came to be one of the regular duties of the soldiers. In 1895, Washburn Brothers erected at Wawona a fish hatchery which was operated by the State Fish Commission, and from here millions of fry have been distributed in the lakes and streams throughout the Park. During 1919, the State Fish and Game Commission operated a temporary hatchery in Yosemite Valley under an agreement with the federal government. This work was not continued during 1920, but the last report of the National Park Service indicates that a permanent hatchery will soon be established in accordance with the agreement referred to.

No sooner had the national park been created than efforts were begun to effect a change of boundaries. As first established, the Park included a large amount of land which was owned by private parties under patents and which was concentrated for the most

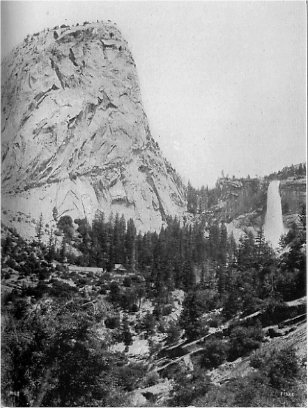

PLATE III Liberty Cap and Nevada Falls. The buildings are the La Casa Nevada, a famous hostelry of the early days which has long since disappeared Photo by George Fiske |

From the standpoint of the administration of the Park there were two reasons for a change: first because of the trouble occasioned by the presence of privately owned lands within the Park; and second because the original boundaries were laid out along straight lines instead of conforming to the natural features of the country, and thus increased greatly the problem of a proper patrol system. For these reasons some of the early Superintendents advised reducing the size of the Park by fixing natural boundaries, so far as possible, and eliminating the bulk of the mineral lands and privately owned timber. Fortunately no attention seems to have been paid to their recommendations. Later Superintendents generally opposed cutting down the boundaries, but strongly urged the importance of extinguishing all private holdings within the Park by purchase or otherwise.

Within a few months after the Park came into existence an attempt was made in Congress to reduce its size. This first attack upon the integrity of the Park was defeated, largely through the efforts of the Sierra Club. As time went by it became clear that one of two things was necessary—either to buy up the private claims within the Park lines, or to revise the boundaries so as to exclude the bulk of these lands. The national government was evidently unwilling to make the necessary appropriation to buy the claims, and finally in 1904 a commission appointed by the Secretary of the Interior visited the Park for the purpose of ascertaining, among other things, "what portions of said Park are not necessary for park purposes, but can be returned to the public domain." This commission, composed of Major Hiram M. Chittenden of the Engineer Corps of the army, R. B. Marshall of the Geological Survey, and Frank Bond of the General Land Office, made a careful study of the situation and recommended the boundary changes that were incorporated in the Act of Congress approved February 7, 1905. This act eliminated about twelve townships on the east and west and added about three townships on the north, fixing the eastern boundary at the summit of the Sierra Nevada and the divide between the Merced and the San Joaquin rivers. In 1906 another small tract on the southwest was cut off, ostensibly to enable an electric line to secure a right-of-way. All of these eliminated lands were added to the adjacent forest reserves.

Further changes in the boundaries may be expected. In fact the National Park Service in its recent reports has suggested the advisability of a further lopping off of grazing land on the west and the addition of a large area on the southeast (eliminated in 1905) which includes such scenic features as the Mount Ritter Range, Thousand Island Lake, and the Devil’s Postpile.

The establishment of the national park resulted in bringing into existence a dual system in the Yosemite region, the State having control of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove, and the national government having control of the surrounding territory. This was an awkward and inconvenient arrangement, necessitating much duplication of administrative machinery and expense. Yosemite Valley was the natural location for the headquarters of the national park, but could not be used for that purpose. Headquarters were therefore maintained at Wawona and the troops were constantly compelled to cross the state park lines in carrying on their patrol work. Superintendents repeatedly called attention in their reports to the anomalous situation and the difficulties which it involved. The disadvantage of dual control was sharply brought out in 1903 by a fire which burned for more than a week in the Illilouette basin, resulting in a rather ill-tempered controversy between the state and national park authorities over the questions as to where the fire originated and whether the state Guardian used due care and vigilance in its extinguishment. This division of authority interfered with the improvement and development of the entire region. The national government, not having control of what were considered the main scenic features, did not feel called upon to make large appropriations, and it was never possible to induce the State Legislature to set aside money enough to properly care for either Yosemite Valley or the Mariposa Big Tree Grove.

As time went by many citizens of California came to feel that it would be better to hand back to the national government the trust received from it in 1864, and a movement was launched with that object in view. It was pointed out that conditions had greatly changed since 1864, at which time there were no national parks; since then the federal government had inaugurated a policy of creating national parks and had manifested a disposition to make adequate appropriations for their maintenance. A comparison of appropriations and results achieved in Yellowstone National Park and in Yosemite State Park proved a powerful argument. Many clubs and civic organizations were enlisted in support of the movement, chief among which in the zeal and effectiveness of its work was the Sierra Club.

Local state pride proved to be the greatest obstacle in the way of the recession, but this was finally overcome, and an act passed by the State Legislature, approved March 2, 1905, receding to the United States Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove. The adjournment of Congress prevented a formal acceptance of the recession until 1906 and hence the transfer could not be effected until that time. The Yosemite State Park finally came to an end August 1, 1906, after an existence of forty-two years. The Superintendent of Yosemite National Park, Major H. C. Benson, at once removed his headquarters from Wawona to the Valley and the central military camp was established on the site of the present Yosemite Lodge. In 1920 jurisdiction in all matters civil and judicial was transferred from the state to the national government.

One of the most important of the forces operating to shape the history of the Yosemite region since the creation of the national park has been the work of the Sierra Club. This organization has been instant in season and out of season in promoting all forward-looking movements affecting California’s great alpine heritage. The life of the Sierra Club has been almost exactly contemporaneous with that of Yosemite National Park. The Club was organized in 1892, but the idea from which it was evolved had its inception in the mind of Professor J. H. Senger of the University of California and was expressed by him as early as 1886. The final impetus was given to the movement by the strongly felt need of some organization to push forward the work that was only begun by the park act of October 1, 1890.

The special purposes of the Sierra Club are thus expressed in the articles of incorporation: "To explore, enjoy, and render accessible the mountain regions of the Pacific Coast; to publish authentic information concerning them; to enlist the support and cooperation of the people and government in preserving the forests and other natural features of the Sierra Nevada Mountains." A detailed account of the doings of the Club would show how faithfully and eagerly its members have carried out these purposes. During the first twenty-two years its work was carried on under the inspiring leadership of John Muir.

The field of the Sierra Club’s work is much more extensive than the Yosemite National Park, but from the beginning it has taken a special interest in this region. Several of its annual outings have been held in the Park and surrounding territory. As early as 1898 a building in the Valley, granted by the State Commissioners, was equipped as local headquarters for the Club, to be used also as a public reading room and bureau of information. A few years later, after the death of Joseph Le Conte, the beautiful Le Conte Memorial Lodge was erected just below Glacier Point. In 1918 it was moved about a quarter mile westward to its present site. In 1913 the Club purchased the Soda Springs property in the Tuolumne Meadows and two years later built upon it the E. T. Parsons Memorial Lodge.

The work of the Sierra Club in opposing attempts to cut down the size of the Park and in urging the recession of the state park has been referred to above. In every time of crisis the Club has stood forth as champion of the forests and the mountains against vandalism and commercialism. The Sierra Club Bulletin, an annual publication, contains a wealth of information about the entire Sierra region—descriptive, illustrative, and scientific. The speech and writings of its members have gone far toward making known to the wide public the true character of the Yosemite region.

This interesting counterpart of Yosemite was discovered in 1850 by a mountaineer named Joseph Screech. Not long before that the Valley was a disputed ground between the east and west slope Indians, but the Piutes from across the range had gotten the upper hand and for years were accustomed to spend some time in Hetch Hetchy in the fall of the year gathering acorns. Screech blazed a trail into the Valley and the rich meadow land became a grazing ground for sheep and cattle. Subsequently the discoverer and two or three other parties took up preemption claims covering most of the Valley floor. The State Geological Survey visited Hetch Hetchy in 1867, and a description of it was published in the San Francisco Bulletin in October of that year. When John Muir first visited the Valley in 1871 he found a sheep owner named Smith in possession. This was doubtless the Smith who later obtained the ownership of a large part of the Valley and of several desirable tracts in the vicinity, and for whom Smith’s Peak and Smith’s Meadow were named. Muir records the fact that in the seventies Hetch Hetchy was frequently called Smith’s Valley.

The number of tourists who visited Hetch Hetchy in the early days was very small, due to its inaccessibility and the superior attractions of Yosemite Valley. John Muir and other enthusiasts did much to acquaint the public with its beauties, but it was only after San Francisco started her fight to secure Hetch Hetchy as a reservoir site that it became widely known. Even then it was better known by report than by actual visitation. The Sierra Club included it in several of its annual outings. In 1905 some Stanford University students conducted a hotel camp there, under the auspices of the Santa Fé railroad, and that served to bring in a number of tourists.

The San Francisco city charter which was adopted in 1900 placed on the supervisors and the city engineer the duty of conducting investigations to determine the best available source for an adequate water supply for that city, this being a matter of pressing importance. After a careful examination of some fourteen suggested sources the Tuolumne River was selected as in every way the best, and there was prepared the first draft of what came to be known as the Hetch Hetchy project, the central feature of the plan being the conversion of Hetch Hetchy Valley into a lake-reservoir and the use of Lake Eleanor as a secondary storage basin. The necessary filings were made to cover the desired water rights and an application was made to the Secretary of the Interior, under the provisions of the act of February 15, 1901, for a permit to use the proposed reservoir and for authorization to construct the necessary dams and other works.

As soon as the plans of San Francisco became known, a movement was put under way to prevent their consummation. This was the beginning of an extraordinary contest, lasting for a dozen years, which was at times waged with considerable bitterness. San Francisco’s first application was denied in 1903 by Secretary of the Interior E. A. Hitchcock. It was renewed in 1905 and again denied. In 1907, after James R. Garfield became Secretary of the Interior, the matter was presented to him, and a hearing was held in San Francisco in July of that year. Further arguments were presented in writing after the Secretary’s return to Washington. Finally, on May 11, 1908, Mr. Garfield granted to the city the rights asked for, but upon two conditions: one that the Lake Eleanor site should be developed to its full capacity before any work should be undertaken on the Hetch Hetchy site; the other that the rights of the Modesto and Turlock irrigation districts should be fully protected.

Under the terms of this grant the city proceeded to buy up the private claims involved, at a cost of several hundred thousand dollars, and to vote a bond issue of $45,000,000. Construction operations had been started when Secretary of the Interior R. A. Ballinger, in February, 1910, after an investigation of the question, ordered the city to show cause why Hetch Hetchy Valley should not be eliminated from the permit granted by Secretary Garfield. This looked at first like a blow to San Francisco’s plans, but it turned out to be quite the reverse, for the fight which was now inaugurated resulted finally in a complete triumph for the city and in the defeat of those who were trying to save Hetch Hetchy from inundation.

A board of army engineers, consisting of Col. John Biddle, Lieut.-Col. Harry Taylor, and Maj. Spencer Cosby, was appointed to advise the Secretary of the Interior on the question. After a preliminary hearing in May, 1910, a continuance of one year was granted in order that a thorough investigation might be conducted. The city hired one of the best engineers in the country and spent over a quarter of a million dollars in an examination of every phase of the question and in the preparation of the reports and plans on which its case finally rested. The final hearing was held November 25-30, 1912, before Secretary of the Interior Walter L. Fisher. The report of the advisory board of army engineers, presented February 19, 1913, was on the whole distinctly favorable to the city. Nevertheless Secretary Fisher declined to act on the matter, since he was about to retire from office and since he also felt that a question of such importance should be passed upon by Congress. Franklin K. Lane, who succeeded Mr. Fisher as head of the Interior Department, in view of his former connection with the case as city attorney of San Francisco, likewise referred the matter to Congress, and the fight was accordingly transferred to that body.

In June, 1913, as an emergency measure, Congressman John E. Raker introduced a bill granting to San Francisco the necessary rights and authorizations for carrying out the Hetch Hetchy water project substantially in the form presented in the plans prepared for the city by John R. Freeman. After extended hearings before the House committee this bill was redrafted in order better to protect the national park and to safeguard the interests of the government. In this form, in spite of the strenuous opposition of many persons from all parts of the country, the bill passed the House by a practically unanimous vote, passed the Senate by about two to one, and was approved by President Wilson, December 19, 1913. Under this act San Francisco was granted the immediate use of both Lake Eleanor and Hetch Hetchy Valley and the extensive engineering works called for by the development of the project were at once put under way. The city is required to build a scenic road along the north side of the lake that will be created by the flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley, and certain other roads and trails the effect of which will be to make more accessible to tourists the country about Hetch Hetchy and the portions of the Park north of the Tuolumne River.

After the recession of the state park in 1906 the administrative machinery already established was continued in effect for some years longer, although the Acting Superintendent found himself confronted with much more exacting duties than formerly. In 1914 a new system was inaugurated. Secretary Lane of the Department of the Interior, in his report for that year, says:

"The conditions in and around these reservations which led to the authorization of the use of the military force in these parks having radically changed, the conclusion was reached that their presence was no longer required in the Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks, and the Secretary of War was so advised. During the past year, therefore, troops have no longer been employed in these reservations and have been superseded by civilian rangers, bringing the latter in closer touch with the actual work of the park management than was formerly practicable when troops were only in the reservations for a few months." The general plan of the patrol system begun under the military régime was continued by the civilian rangers.

Mark Daniels was the first Superintendent under the new arrangement. On March 10, 1914, he was "commissioned as landscape engineer in the Yosemite National Park for the purpose of preparing a comprehensive plan for the development and improvement of the floor of the Yosemite Valley covering the best locations for roads, trails, and bridges, so as to bring into view the full scenic beauty of the surroundings, the clearing and trimming of suitable areas of woods to provide attractive vistas, the proper location and arrangement of a village in the Yosemite Valley, etc." An important step taken in 1915 was a change in the method of handling concessions, placing all the hotels, camps, and lodges (with the exception of Camp Curry) in the hands of one company under a long term lease, thereby providing for the building of two new hotels, one on the floor of the Valley and one at Glacier Point. In June, 1914, Mark Daniels was appointed General Superintendent and Landscape Engineer for all the national parks under control of the Department of the Interior. This was as far as the executive branch of the government could go in the reorganization of national park administration. The final step awaited the action of Congress. For some years the Secretary of the Interior, seconded by the President, had been urging the establishment of a national park service. This was finally done by an act of Congress which was approved August 25, 1916. The new bureau was organized in the spring of 1917. As its first Director Mr. Lane appointed Stephen T. Mather, who had already, as assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, had general oversight of national park affairs. Much of the recent development in this field has been due to the clear vision, enthusiasm, and untiring energy of Mr. Mather. The establishment of the National Park Service marks the beginning of a new era in national park history.

In the last decade a change has come over Yosemite—a change that can be fully appreciated only by those who have seen both the old Yosemite and the new. There has come into existence a new attitude on the part of the general public, and the administrative development just described is in part a cause and in part an effect of this new attitude. It is now seen that Yosemite is not simply the glorious valley of that name, nor the remarkable old Sequoias, but a vast alpine wonderland containing, besides these, many other features quite as much worth seeing. There are several factors which have an important bearing upon this new conception, and it is necessary to mention a few of them.

The Park has been made accessible to a degree that was formerly only dreamed of or hoped for. First, the building of the Yosemite Valley Railroad has made it possible for the tourist to ride in comfort to the very edge of the Park, giving a much more effective approach to the Valley through the wild gorge of the Merced River. The building of this railroad was the final outcome of many suggestions and proposals for a wagon road or an electric road or a steam road designed to do away with the worst discomforts attending a visit to Yosemite. It follows the route which was pronounced the best by two different commissions appointed by the Secretary of the Interior. The right of way up the Merced River canyon was granted September 5, 1905, and the road was opened to travel in the spring of 1907. Second, the admission of automobiles has popularized the Park in a way that nothing else could do. This policy was inaugurated near the close of the 1913 season. At the present time approximately two thirds of the visitors to the Park enter it in private automobiles. Third, the rehabilitation of the Tioga Road has opened the great upper Yosemite region to thousands who would never have gone there under the old hard conditions. This road, the importance of which was stressed by every Acting Superintendent of the Park, was purchased and presented to the government in 1915 through the generosity of Stephen T. Mather and a few others. The State of California purchased the portions of the road outside of the Park and built an extension down Leevining Creek to connect with the highways on the eastern side of the range, thus making this old road an important link in a great highway system. Fourth, the removal of the toll annoyance from the roads and the construction of new roads and trails within the Park have added immensely to the comfort of tourists and the ease of getting about to points of interest. The park road and trail system is not yet complete, but enough has been done to show beyond peradventure how richly it pays in the finer sense to open up the mountain playgrounds of the people.

Since the recession of the state park in 1906 and concurrent with the changes outlined above, travel to Yosemite National Park has increased thirteenfold and national appropriations have grown from a few thousand to $300,000 for the season of 1920. With these changes the old Yosemite has become but a memory. The long hard trip over mountain roads followed by a sojourn in the quiet and restful Valley has given place to comfortable automobile and train service and life in modern camps and hotels. In winter, in early spring, and in late fall the Valley still bears much of its old-time restful atmosphere, but during the height of the season (July) the population numbers ten thousand or more. The policy of the National Park Service in making the Park "liveable" and more and more accessible is unquestionably the right one. Even now the charm of the old Yosemite can still be found by those who are willing to pursue it, for in Tuolumne Meadows, at Tenaya Lake and at Merced Lake are delightful little mountain chalets; and in spite of further encroachments of civilization there will always be the wildness of nature for those who seek it.

Bunnell, Lafayette H., 1911. Discovery of the Yosemite, and the Indian War of 1851 which Led to that Event. 4th ed. (Gerlicher, Los Angeles) 355 pp., 34 pl., 1 map.

Hutchings, James M., 1888. In the Heart of the Sierras. (Pacific Press, Oakland.) 496 pp., illus., maps.

King, Clarence, 1902. Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. 6th ed. (Chas. Scribner’s Sons, New York.) 378 pp. (Yosemite on pp. 165-190.)

Kuykendall, Ralph S., 1919. “Early History of Yosemite Valley, California.” Dept. of Int. Park Service Bulletin. 12 pp.

Muir, John, 1911. My First Summer in the Sierra. (The Century Co., New York.) 354 pp., illus.

Sierra Club, San Francisco, 1893-1920. The Sierra Club Bulletin, vols. i-xi., illus.

1 Only the most important works are listed in the references following articles in this volume. These include practically all of the non-technical literature now available on the various subjects.

Next: Indians of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Illustrations

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/handbook_of_yosemite_national_park/history.html