Yosemite Valley, 1892.

Published by the Edinburgh Geographical Institute.

[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Resources > Chapter III: Administration of The Yosemite Grant and Yosemite National Park, 1890-1905 >

Next: 4: Cavalry 1905-1915 • Contents • Previous: 2: State Grant 1864-1890

A. The U. S. Army Enters Yosemite 311

1. The U. S. Army Becomes the Regulatory force in the New California Parks 311B. Trails, bridges, and Roads 320

2. Aspects of Military Management 312

3. Contributions of the U. S. Army to the Present National Park System 318

1. Trails and bridges 320C. Construction and Development 349a) Pre-Army Trail System 3202. Toll Roads 341

b) Blazes 321

c) Army Troops Begin Improving routes 325

1. State of California 349D. Natural Resource Management 365a) Pavilion 3492. Concession Operations 349

b) Powerhouse 349a) Wawona Hotel 3493. Sierra Club 354

b) Cosmopolitan Bathhouse and Saloon 350

c) Camp Curry 351

d) Degnan Bakery 352

e) Fiske Studio 352

f) Foley Studio 352

g) Jorgensen Studio 353

h) Boysen Studio 353

i) Best Studio 354

j) Studio of the Three Arrows 354a) Creation of Club 3544. U. S. Army 359

b) LeConte Lodge 357a) New Camp buildings 359

b) Arboretum 360

1. Continuing Charges of Spoliation of Yosemite Valley 365E. A New Transportation Era Begins 388

2. The Sheep Problem 368a) The Sheep industry in the 1890s 3683. Grazing on Park Lands 372

b) Army Measures to Combat Trespassing 370

4. Poaching 373

5. Fish Planting 374

6. Forest Management 377

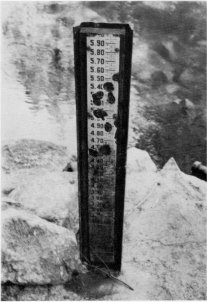

7. Stream Flow Measurements in Yosemite Valley 377

8. Origins of a Major Conservation Battle 380a) Initiation of the Hetch Hetchy Project 380

b) The Secretary of the interior Denies Mayor Phelan‘s Applications 385

1. Railroad Lines to Yosemite 388F. Private Lands and boundary Changes 391a) Yosemite Short Line Railway Company 388

b) Yosemite Valley Railroad 389

1. The U. S. Army Becomes the Regulatory Force in the New California Parks

Acts of Congress approved 25 September and 1 October 1890 set aside three separate tracts of land in the state of California. The statutes required the Secretary of the Interior, who had exclusive control over the properties, to publish rules and regulations for the preservation from injury of all timber, mineral deposits, and natural curiosities or wonders. He also had to provide against the wanton destruction of the fish and game in the park and against their capture for either merchandising or profit, as well as remove all trespassers.

With the establishment of Yellowstone in 1872 and of Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant national parks in 1890, the federal government attempted to initiate a system of national preserves for public use and enjoyment. The 1864 act establishing the Yosemite Grant, however, legislated no “national” laws or appropriations to ensure the execution of the Secretary of Interior’s new and complex responsibilities. In addition, Congress immediately returned to more important Civil War matters without addressing the need for a strict regulatory agent to patrol boundaries, guard the forests and streams, enforce rules and regulations, and generally protect government interests.

Without either a legal system, annual appropriations, or the necessary administrative facilities to accomplish the purposes set forth in the laws, the Secretary of the Interior advised the President of the United States on 4 December 1890 that the best arrangement for preventing timber cutting, sheep herding, trespassing, and spoliation would be to station a troop of cavalry in Yosemite and another in Sequoia to administer it and General Grant. The President approved instituting in those areas an administration similar to that in Yellowstone, and army detachments occupied those parks during part of every year after 1891; until 1900 they operated without congressional sanction.

The precedent for military management of the California parks had been set at Yellowstone National Park. In the first years after establishment of that area, the Department of the Interior had been helpless in preventing spoliation, the civilian administrators having neither the physical nor the legal force to prevent depredations. Although conditions became so appalling that some pessimists called for abandoning this first formal federal experiment in conservation, a few staunch supporters of the idea managed to get a clause included in the Sundry Civil Act of 3 March 1883 that authorized the Secretary of the Interior to request the Secretary of War for troops for the protection and preservation of the park if needed.

In 1886, after Congress refused to appropriate money for Yellowstone’s administration, the Secretary of the Interior did ask the Secretary of War for troops of cavalry to protect the area. That system of military management was so effective that it was later extended to the Yosemite, General Grant, and Sequoia national parks, without a legal basis, however, because the 3 March act did not legally apply to later parks. The military administration of those four parks comprises a unique period in our history, because the army maintained and protected those lands for years without legal sanction or official law enforcement procedures. The army successfully functioned as a civil government—a role never previously or since required of it.

2. Aspects of Military Management

Troops protected and patrolled the California parks only during the summer months, from May to October, in the hopes that the heavy snows of winter would deter intrusion by trespassers during that time. Two troops of cavalry served in the three parks, leaving the Presidio of San Francisco in early May and arriving in the parks two weeks later after an overland march of 250 miles. One troop went south to patrol Sequoia and General Grant parks, the other stayed in Yosemite. The officer in charge of the southern detachment became acting superintendent of the Sequoia National Park, the other officer being designated acting superintendent of the Yosemite National Park. Both submitted annual reports to the Secretary of the Interior. The army never established a permanent military post at Yosemite, only a temporary summer headquarters on the southern boundary near Wawona and a semipermanent post later in Yosemite Valley.

When U. S. troops first occupied the three California parks in 1891, they found conditions very similar to those in Yellowstone. Boundaries were unmarked, roads and trails were practically nonexistent, and people had -for years been availing themselves of hunting, fishing, mining, and grazing opportunities on those vast public lands. The area of army responsibility in Yosemite comprised a huge, relatively uncharted wilderness easily penetrated by trespassers. The cavalry units assigned to Camp A. E. Wood received few instructions on problem solving and little money with which to work. Usually army officers served only one season as acting superintendent and it was difficult within that time to become well acquainted with the park and its needs. After 1897 a new acting superintendent was appointed each year. During one or two periods, as many as three different acting superintendents served within a year. The resulting lack of continuity in policy and in interpretation of the rules, and the fact that each new superintendent had only begun to learn his duties by the time he left, were objectionable features of this system of management. In the absence of a penal code, military commanders often resorted to ingenious expedients and cunning contrivances as a substitute for legal methods.

After Congress provided a legal structure. for Yellowstone Park in 1894, but failed to make the act applicable to the California parks, pleas by California superintendent for additional legislation became more insistent. The Secretary of the Interior forwarded those requests in each of his annual reports to Congress, with no affect. The illegal aspects of using U. S. troops to perform civil duty surfaced again in 1896, when the Secretary of War questioned the Secretary of the Interior’s routine

|

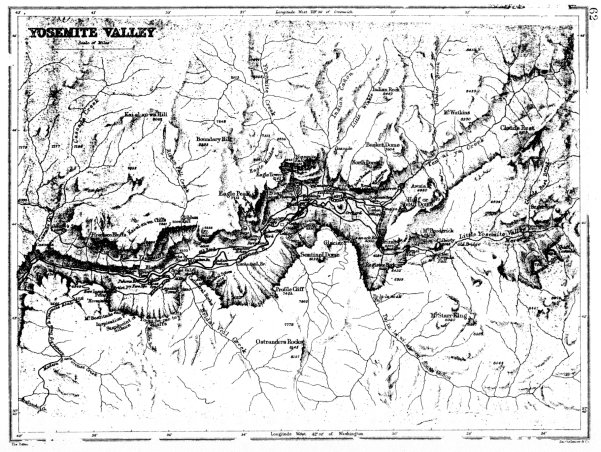

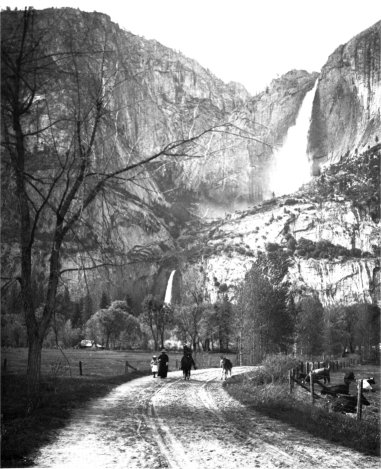

Illustration 43.

Yosemite Valley, 1892. Published by the Edinburgh Geographical Institute. |

[click to enlarge] |

For the duration of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Secretary of War suspended the annual assignment of troops to the parks. During that time a civilian, J. W. Zevely, special inspector for the Department of the Interior, nominally protected the parks. As acting superintendent, he immediately appointed eleven men as forest agents to patrol the park. Four special agents of the General Land Office, under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, also reported to Zevely for duty. Two of them were each placed in charge of a squad of men in Yosemite and two were dispatched to Sequoia and General Grant parks. Those civilians continued the army’s methods of expelling trespassers, extinguishing fires, and confiscating firearms.

On 1 September army personnel—Capt. Joseph E. Caine and the First Utah Volunteer Cavalry—returned to Yosemite. After those troops left in the fall, funds were found to appoint Archie O. Leonard, early guide and pack train boss in the area, and Charles T. Leidig, first white boy born in Yosemite Valley, as the first official civilian rangers for the park, with direct charge of park matters. They remained in Yosemite throughout the winter and for several years thereafter. During that time they willingly assisted the army troops and became indispensable in the administration of affairs in the park. Meanwhile, opposition to the extra-legal military administration was rising on several quarters and questions mounting in the War Department regarding the legal authorization for such an employment of the army.

Congress became the arbiter of the matter, and by act of 6 June 1900 authorized and directed the Secretary of War, at the request of the Secretary of the Interior, to detail troops to prevent trespassing for any of the purposes declared by the statute to be unlawful. The presence of troops in the California parks finally became legal.

The act of Congress approved 6 February 1905 authorized all persons employed in forest reserves and national parks to make arrests for the violation of rules and regulations. Still no real penalties existed other than expulsion, so that this act was only a beginning. In 1910 the acting superintendents of the California parks appended to the published rules and regulations of Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant national parks an excerpt from an act designed to protect Indian reservations and allotments. The portion cited provided a fine and imprisonment for anyone cutting trees or leaving a fire burning upon land reserved by the U. S. for public use. This remained the only piece of punitive legislation available during the military administration of the California parks.

After the recession to the federal government of the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove in 1905, military headquarters moved to a central location in Yosemite Valley and military protection extended throughout the valley and high country. The army continued to detail troops to Sequoia and Yosemite until 1914, when a force of civilian rangers replaced them upon the insistence of the military commanders that conditions had materially altered since the establisment of the parks.

During the twenty-three years between 1891 and 1914, a succession of eighteen army officers (see Appendix E) and various cavalry units functioned admirably as guardians of the meadows, forests, and animal life of Yosemite. The military commanders chosen to perform nonmilitary duties in the parks were men of high caliber who took their trust seriously. Some officers truly distinguished themselves—among them Maj. Harry C. Benson and Maj. William W. Forsyth. Benson, especially, is renowned for his explorations, map making, fish planting, and determination to end the encroachments of sheepmen and cattlemen. He was also the guiding force behind trail location and construction.

Several individuals carried the army tradition into the later civilian administration of the park. Gabriel Sovulewski first came to Yosemite in 1895 as Quartermaster Sergeant with the army. Honorably discharged after service in the Phillipine Islands in 1898, he worked as a civilian guide and packer in Yosemite in 1901. In 1906 he returned as park supervisor and looked after park interests during the winter. He also served as acting superintendent during the early years of civilian administration from 1914 to 1916. Many of the park’s trails and roads were built under his supervision. Subordinate officers and enlisted men, such as Lt. N. F. McClure, also made important contributions in backcountry exploration and map making, while others helped stock the Yosemite rivers and streams with trout. Place-names throughout the High Sierra commemorate many of those army officers and men.

3. Contributions of the U. S. Army to the Present National Park System

The U. S. Army began its work in the California parks during a relatively calm period in world affairs. As a result, troops were regarded less as a combative force than as a peacetime regulatory agent to be called upon in times of need. Initially, a hostile neighboring population, accustomed to free use of public land for grazing, hunting, lumbering, and mining, resented curtailment of those privileges in Yosemite, and in their resentment attempted in every way possible to circumvent the authorities. Attitudes gradually changed through the years, however, and more people became firm believers in preservation and protection of resources through the establishment of national parks.

The United States Army filled a void in early park administration that could not be filled any other way. To a large degree army officers developed the park policy inherited and later refined by the National Park Service. More important, perhaps, without benefit of a well-defined legal system and hampered by the absence of punitive legislation, army troops saved Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant national parks from destruction just as they had Yellowstone. At the same time, they managed to instill in the surrounding populace a regard for conservation of America’s natural resources.

Park duty often involved incurring the emnity of homesteaders and cattlemen and sheepmen and occasional hostility from the state Guardian and commissioners. Local interests in the counties surrounding the park affected by the creation of federal forest reservations resented losing thousands of acres of taxable land and valuable timber and mining rights. Relations between them and the various park administrators became more and more strained over the years. Despite the difficulties, park details were not an unattractive burden for either army officers or men. The former relished the relatively autonomous and independent command, and the men enjoyed the pleasant, summer-long relief from routine army duties. Troops also encountered less discipline, drill, and restraint. They became good field soldiers with six months of intensive field training to their credit at the end of each year.

Military authorities made a major contribution toward the conservation of natural resources, managing to convince the public, despite their determined enforcement of regulations by often unorthodox and severe methods, that preservation was necessary and even advantageous. Communities around the parks gradually began to favor strict compliance with the rules, convinced by the acting superintendents of the recreational and economic advantages of park existence.

As their legacy to America’s national parks, the military developed workable administrative procedures; made physical improvements, including the construction of roads, trails, bridges, campgrounds, and administrative buildings; formulated policies on natural resource management, conservation, and protection, and on private lands and leasing; initiated interpretive and naturalist programs; collected and analyzed scientific data; thwarted actions inimical to the interests of the parks; and protected them against the caprices of politicians and wanton destruction by merchants and businessmen. The U. S. Cavalry protected the beginnings of the National Park System when no other source of protection was feasible or available. When ultimately the park ideal gained a foothold and conservation became a natural part of the nation’s thinking, the presence of a military force became inappropriate. At that time, the transition from the military administration to a civil one was less abrupt because many military personnel accepted discharges from the army and became the professional cadre around which the first civilian ranger force formed.

Conditions in Yellowstone had ultimately forced the enactment of a comprehensive organic law for its government, to protect the resources and punish criminals. By the early 1900s such conditions as existed in Yellowstone prior to that ‘legislation appeared in Yosemite, resulting in the inability of the military to efficiently enforce the rules and regulations the Interior Department prescribed. The interests of all concerned, but especially those of the United States, required the enactment of laws suitable for the dignified and orderly government of the parks. Continued military government was not perceived to be the final answer for Yosemite any more than it had been for Yellowstone. Parks required civil administration, which could be most effectively and appropriately provided by the enforcement of suitable laws through an adequate administrative system by qualified civil officials.1

[1. Good information on early army administration of America’s national parks is found in Harold Duane Hampton, “Conservation and Cavalry: A Study of the Role of the United States Army in the Development of a National Park System, 1886-1917,” Ph. D. dissertation, University of Colorado, 1965, which has been used as a source for some of the statements in this section. Also see Hampton, How the U. S. Cavalry Saved Our National Parks (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971). ]

1. Trails and Bridges

a) Pre-Army Trail System

Indian trails connecting Wawona, Glacier Point, Yosemite Valley, and the Sierra uplands comprised the most traveled routes in the Yosemite region when the army took charge. The first detachments found only a few marked trails beyond the rim of Yosemite Valley. Those rough routes had been established first by Indians and then slightly improved by packers transporting goods across the Sierra to miners on the east side, by wandering stock, cattlemen, and miners, and by sheepherders and the packtrains supplying them. The army improved and blazed those routes during their patrols, but also had to forge new ones. Abandonment or rerouting of old trails sometimes became necessary to avoid slides, to improve grades, or to shorten distances. Private contractors constructed many of the new trails as the Interior Department made appropriations available, but army engineers and army labor planned and constructed most of the road and trail systems during those early days. Funds for the construction and repair of trails first became available in 1899, with annual appropriations then following regularly. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Garrard of the Fourteenth Cavalry was the first acting superintendent (1903) who personally supervised trail construction.

The existing trail system in the Yosemite backcountry had its inception in the early U. S. Army patrol work, with most of the main features of today’s system laid down by 1914. During the army administration, the geography of the Yosemite wilderness was transferred to paper and not simply a part of oral tradition. Because cavalry units assigned to the park changed each year, routes had to be clearly established and mapped early in the military administration to avoid duplication of effort. One interesting aspect of the army’s surveying and mapwork is that it probably caused the loss of many original place names. Early penetrators of the wilderness had bestowed names on certain areas and topographical features that reflected events concerning its discovery or personal experiences involving that site. Those had been in common usage for years, but were gradually replaced in the 1890s with names reflecting new experiences and a new authority. Because of their placement on paper, those new designations became permanent references to particular areas.2

[ 2. James B. Snyder, “Yosemite Wilderness—An Overview,” n.d., typescript, 4 pages, section of draft of Yosemite Wilderness Management Plan, in Yosemite Research Library and Records Center. ]

b) Blazes

A valuable group of resources within Yosemite National Park’s backcountry are the blazes left by individuals who used the

|

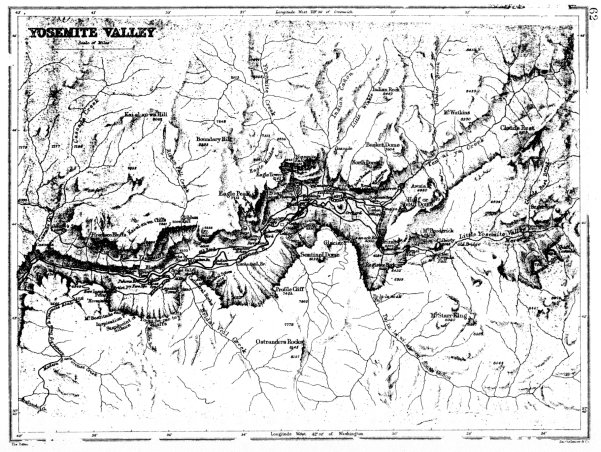

Illustration 44.

Outline map of Yosemite Valley. From Hutchings, Yo Semite Valley and the Big Trees, 1894. |

[click to enlarge] |

[3. Allan (Shields?) to Keith (Trexler?), 29 July (1959-60?), Yosemite-Trails, Y-8, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center; John Mahoney to Doug Hubbard, 20 August 1958, in Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

[4. Scott Carpenter, Review of Historic Resource Study, 1986, 5.]

[5. Jim Snyder, Historic Resource Study review comments, 1986, 21.]

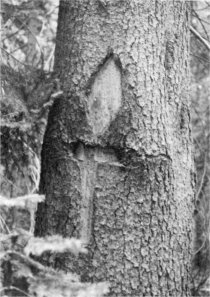

These blazes are an interesting and significant reminder of undocumented backcountry grazing and mining operations and trailblazing. They indicate areas of concentration as well as early trail marking and map making activities within the park. Presently they are threatened by new wildfire let-burn policies. Many of the earlier sheepherder blazes may also have cultural significance, because most of the carvers were foreign born. Examples of the different types of blazes should be preserved. A record of their locations would be a useful guide to early trails in the region. Probably every year marked trees are dying and falling, resulting in the loss of these symbols of significant exploration and land use.

c) Army Troops Begin Improving Routes

Captain Abram Epperson Wood, commanding Company I, Fourth Cavalry, became the first acting superintendent of Yosemite National Park in 1891 and continued in that position until 1894. Establishing a base camp on the South Fork of the Merced Rivei—later referred to as Camp A. E. Wood—about one mile west of and on’ the opposite bank from the Wawona Hotel, the new administrator proceeded to tackle Yosemite’s problems. He had not been informed of his duties before his arrival, nor were maps of the area provided, necessitating that he purchase a small township map of the park printed in San Francisco so that he could locate the park boundaries! Once he had determined the boundaries, Wood periodically detached units to patrol them for trespassing cattle and sheep.

The road of greatest use to army troops patrolling the park was the “Big Oak Flat and Tioga Road,” which left the Big Oak Flat Road about five miles into the park and continued east to the Sierra crest. Although not much used for the two or three years prior to the army’s arrival and obstructed with fallen trees and washouts, it remained a good mounted trail. Wood’s troops also frequently utilized the section of the Mono Trail that began at Wawona, wound up along the South Fork of the Merced, turned northeast probably in the vicinity of Alder Creek, crossed the main Merced River just above Nevada Fall, and then dropped over the divide between it and the Tuolumne River, crossing the latter at Tuolumne Meadows and then proceeding east over the summit through Bloody Canyon.

Three other trails often served patrol purposes: the Virginia Trail, entering the park probably near Virginia Canyon and heading down toward the Tuolumne River at the lower end of Tuolumne Meadows; a trail from Mount Conness to Tuolumne Meadows; and one

|

Illustration 45.

Diamond and T blazes on lodgepole pine, Ostrander Lake Trail. Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

The track from Mariposa to Hite’s Cove and on into the valley was difficult and seldom used. The army did blaze a few lesser trails in the park to preserve them because they facilitated communications and police work. They mainly comprised old stock trails that would be obliterated as grazing was phased out unless the army accomplished preservation work. One of the most pressing needs of the army was a trail system consisting of a route running around the park inside the boundaries, with other trails branching off to important points, and including log bridges over main streams.

By 1894 the Lower Iron Bridge across the Merced River near where the Big Oak Flat Road entered the valley still had not been rebuilt after collapsing from snow loads years before. That situation forced travelers to follow along the north side of the valley to the Upper Iron Bridge spanning the river almost directly opposite Yosemite Fall. Additionally, Lt. Col. S. B. M. Young, Fourth Cavalry, acting superintendent in 1896, stated that the bridge for saddle and pack animals over the Tuolumne River in the Hetch Hetchy Valley needed to be repaired or abandoned. That structure, of log stringers supported on timber cribs filled with rock and floored with split timber, served as the only means of communication with the section north of the Tuolumne River until August, when the fords became passable. Young also reported the need for two log bridges enabling mounted patrols and pack animals to pass through the southeast section of the park early in the season. Large rocks that covered the streambeds in that region, coupled with strong spring currents, made fording almost impossible.6

[6. S. B. M. Young, Lt. Col, Fourth Cavalry, Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park to the Secretary of the Interior, 1896 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896), 8.]

An act of Congress approved 1899 appropriated $4,000 for the protection of the park and the construction of bridges, fencing, trails, and the improvement of roads other than toll roads. Contracts were immediately entered into for the construction of a bridge across the Merced River and for the repair of a trail from the bridge to its connection with the Coulterville wagon road, a distance of fourteen miles.

In 1901 a new trail, to Dewey Point, followed the south rim of the valley from near Sentinel Dome via The Fissures, across Bridalveil Creek some distance back of Bridalveil Fall, then on to Dewey and Stanford points and the stage road at Fort Monroe. At that time the valley floor contained twenty miles of carriage road and twenty-four miles of saddle trails.7

[7. D. J. Foley, Yosemite Souvenir and Guide (Yosemite, Calif.: “Tourist” Studio-office, 1901), 19, 24, 45, 54.]

By the end of fiscal year 1901, a contractor had nearly completed a bridge over Wet Gulch (exact location unknown), and Acting Superintendent L. A. Craig, Major, Fifteenth Cavalry, recommended repair and/or construction of the following trails and roads:

repair of trail from head of Chilnualna Fall to Devils Post Pile, 38 miles;

construction of trail from Clouds Rest trail to Lake Merced, 5 miles;

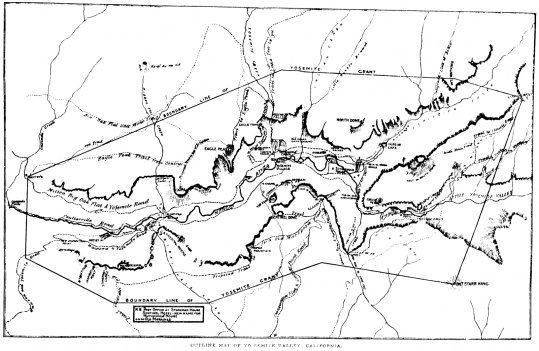

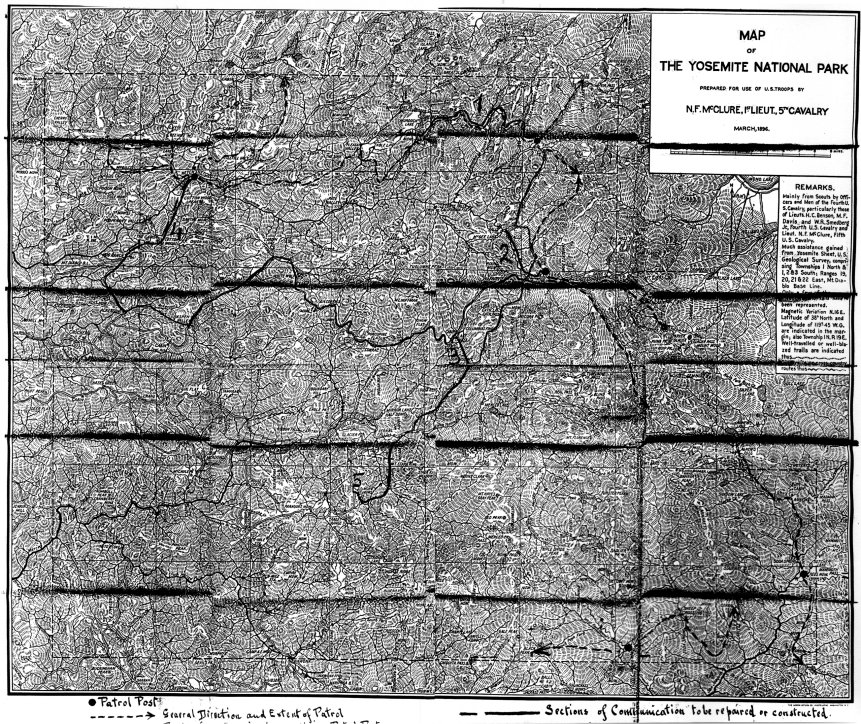

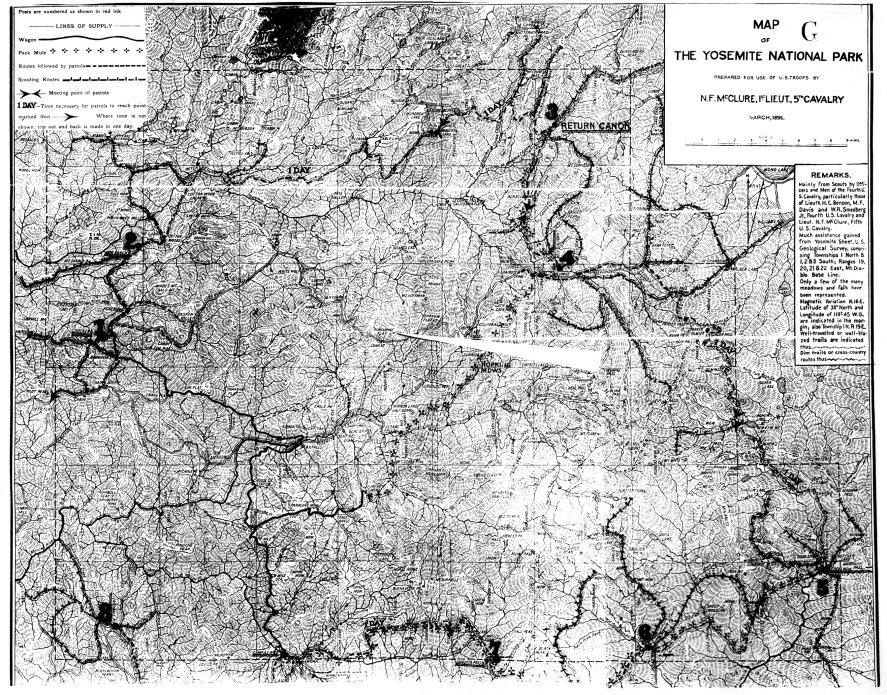

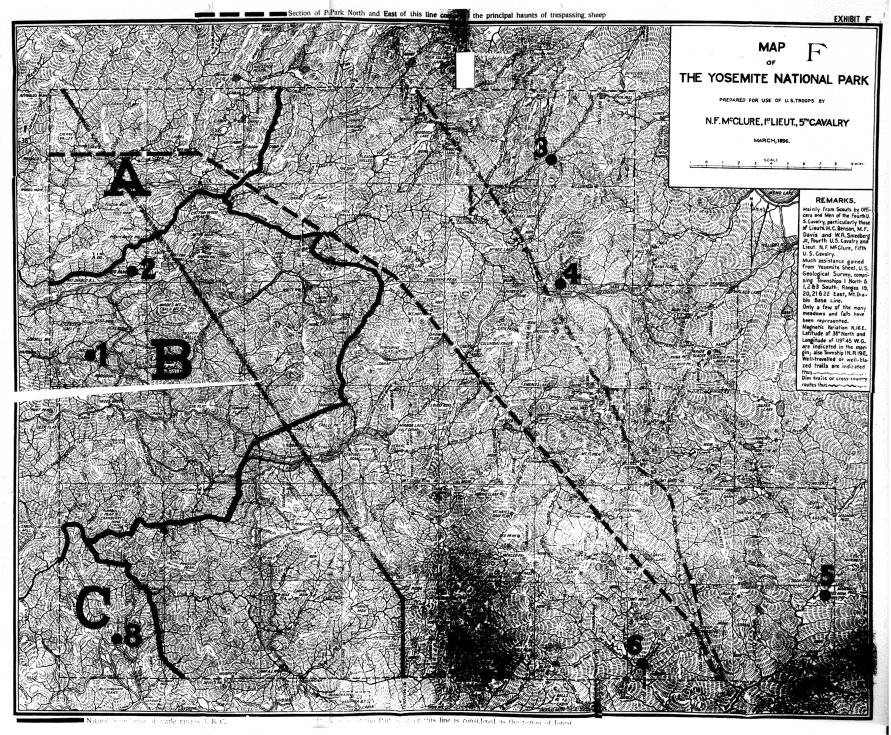

repair of trail from Tiltill trail east side of Rancheria Creek to “The Sink” (not located on modern maps, but see McClure’s 1896 map, Illustrations 43-45), 10 miles;

repair of trail from Poopenaut Valley to Lake Eleanor, 9 miles;

repair of trail from headwaters of San Joaquin River to head of Bloody Canyon, 30 miles;

repair of trail from Lake Tenaya to White Cascades on Tuolumne River, 9 miles;

repair of trail from Lake Eleanor to Lake Vernon, 11 miles;

repair of trail from Lake Vernon to Tiltill Valley, 8 miles;

construction of bridge over Tuolumne River near Lembert’s Soda Springs to be used by saddle and pack animals; and

construction of trail from Lake Ostrander to Crescent Lake, 7 miles.8

[8. L. A. Craig, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” 10 October 1901, in Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1901. Miscellaneous Reports. Part L Bureau Officers, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901), 552-54.]

Illustrations 46-48. “Map of the Yosemite National Park Prepared for Use of U. S. Troops by N. F. McClure, 1st Lieut., 5th Cavalry, March, 1896.” This map is especially useful for locating early place-names and structures. These three copies show wagon roads, army patrol posts, direction and extent of patrols, routes used by packtrains supplying the posts, and cattle- and sheep-grazing areas. From Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Relating to National Parks, 1872-1907 (Yosemite), RG 79, NA.

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

During fiscal year 1902, the army contracted for construction of several trails:

from Alder Creek to Peregoy Meadow,

from Devils Post Pile to Bloody Canyon,

from Mono Meadow to Lembert’s Soda Springs,

from Ostrander Lake to Crescent Lake,

from Lake Eleanor to Lake Vernon, and

from Lake Vernon to Tiltill Valley.

A bridge was also built over the Tuolumne River near Lembert’s Soda Springs.9

[9. O. L. Hein, Major, Third U. S. Cavalry, Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park hn California to the Secretary of the Interior, 1902 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902), 4.]

During the 1903 season, the establishment of permanent patrolling stations, manned by four to six men each, enabled troops to more thoroughly guard and patrol the park. Captain Benson and the civilian rangers advising him had suggested this system. Subposts, each consisting of one noncommissioned officer and from three to nine privates, were established at Little Jackass, Agnew’s, Lembert’s Soda Springs, Return Creek (above Tuolumne Meadows), in Hetch Hetchy Valley, at Crocker’s, and at Buck Camp.10 Troops serving at those substations were relieved once a month. Detachment commanders made daily patrols to cover all approaches to the park and all territory where sheepmen and poachers might be found. An officer’s patrol visited and inspected each substation at least once a month.

[10. Little Jackass Meadow was part of Yosemite National Park from 1890 to 1905. Its name was changed to Soldier Meadow in 1922. Theodore C. Agnew, a miner, settled in the meadow bearing his name, north of Devils Postpile NM, in 1877. Agnew guided army troops patrolling the park. Peter Browning, Place Names of the Sierra Nevada (Berkeley: Wilderness Press, 1986), 2, 204.]

The building and repairing of trails progressed well during 1903 and all contract work was completed except for the trail from The Sink to Rodgers Lake. Soldiers used axes, hatchets, and saws to open up about sixty miles of trail that had become overgrown or blocked by fallen trees. Expenditures had been made on trails from Poopenaut Valley to Lake Eleanor, from Tenaya Lake via McGee Lake to Smoky Jack Meadows (named for sheepman John Connell), from Rancheria Creek to The Sink, from the west summit of the North Fork of the San Joaquin River to Kings Creek and for a bridge across that river, from near Upper Chilnualna Fall to Johnson and Chiquito lakes, from Rancheria bridge connecting with the Poopenaut trail to Lake Eleanor, and from The Sink to Rodgers Lake. Other work that needed to be done included repairing and tarring the two suspension bridges in the valley of the Merced River near Hennessey’s ranch site.11

[11. Jos. Garrard, Lt. Col., Fourteenth Cavalry, Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park in California to the Secretary of the Interior, 1903 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1903), 4-5, 7-8.]

In the first part of the 1904 season, the army again established patrol posts, divided into eastern and western sections, with an officer in command of each. The commander of the eastern one took post at Soda Springs, the commander of the western section remained at Camp A. E. Wood. Each section commander inspected each of his posts at least once during his tour. After all posts had been set up, the patrols of adjoining posts were required to meet and exchange mail or messages every week, resulting in a complete circuit of patrols from the first post back to Camp Wood. Each post patrolled to its front beyond the line of the reservation.

Because small numbers of cattle had been found trespassing in the park, the troops constructed an impoundment corral at Big Oak Flats, near T. H. Carlin’s place on the South Fork of the Tuolumne River. Acting Superintendent Maj. John Bigelow, Jr., requested authority to grant a permit for cattle grazing on government land because he believed that cattle grazing helped diminish forest fires, that cattle trails served as useful fire guards, and that the presence of cattle in the park assured the help of cattlemen and herders in preventing and extinguishing forest fires. He also argued that cattle ranging on government land would lead to the fencing in of the patented lands to exclude those cattle and would thus aid in defining more clearly the metes and bounds of those lands. Bigelow also stated that “cattle are a picturesque feature of the landscape, relieving the monotony of wastes of grass and wood.”12 The only work accomplished on roads or trails during that time involved construction by the troops of a road from the Glacier Point road to Mono Meadow.

[12. John Bigelow, Jr., Major, Ninth Cavalry, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” 30 June 1904, in Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1904. Miscellaneous Reports. Part L Bureau Officers, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 380-81.]

Expenditures incurred up to 15 September 1904 included repairing the trail from Rodgers Lake to Smoky Jack Meadow, constructing a trail from Lembert’s Soda Springs to the Palmer trail, repairing parts of the trail from Hog Ranch to Hetch Hetchy, constructing a trail from Hopkins’s place (Hopkins Meadow—roughly the junction of the Sunrise and Highwater trails below Clouds Rest) to Merced Lake, repairing the trail from Crescent Lake to Johnson Lake, repairing the trail from Chilnualna Fall to its junction with the trail from the “target range,” tarring the suspension bridges over the Merced River and Wet Gulch, and constructing a footbridge over the South Fork of the Merced River near Camp Wood.

On 30 April 1905, Capt. H. C. Benson, Fourth Cavalry, became acting superintendent and reestablished headquarters at Camp A. E. Wood and outposts for patrol purposes in outlying districts—at Crane Flat, Hetch Hetchy Valley, Jack Main Canyon, Aspen Valley, Merced Lake, Soda Springs, and Matterhorn Canyon.

Trails constructed or improved during 1905 led

from a point on the Lake Vernon-Hay Stack Peak trail eastward into Jack Main Canyon and out from Tiltill Mountain to Tiltill Valley;

from a point near Breeze Lakes, via Fernandez Pass and the headwaters of Granite Creek, to Post Peak, Isberg Pass, and down the east bank of the Merced River to Merced Lake;

from a point on the above trail in the McClure Fork Canyon northeastwardly via Vogelsang Peak, Fletcher Lake, and Tuolumne Pass to the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne where Ireland Creek empties into it; and

from a point in Jack Main Canyon, where the trail from Tiltill Mountain reaches the canyon floor, northeast along the east bank of Fall River, up Jack Main Canyon.

Work on these trails proved very difficult. The new paths were well constructed, however, and their entire lengths could be ridden on horseback. Because all the trails ran at high altitudes, travelers received spectacular views of the park. Other construction included a bridge across Rancheria Creek.

2. Toll Roads

The future of the four toll roads into Yosemite Valley, which passed through the national park, quickly became a topic of discussion among early army administrators. Because the initial road construction had been costly and the severe winters entailed expensive repairs each spring, the various road companies charged high toll rates for passage. To many visitors the payment of tolls entailed an economic hardship when added to the exorbitant prices they had to pay for hay and grain in the valley. In addition, tolls seemed incompatible with the concept of a national resort and recreation area open to all, rich and poor alike. The army believed that federal acquisition of those roads would encourage more public use of the park and would enable maintaining them in proper condition to facilitate the supply of army troops and the discharge of their duties in enforcing the rules and regulations of the park.

Because the roads had been built under the authority of both national and state law, the owners could not be deprived of their property except upon reasonable compensation. The Secretary of the Interior had the power to regulate, but not to prohibit, the taking of tolls on roads in the national park outside of Yosemite Valley. The absolute prohibition by the federal government of levying tolls would be tantamount to confiscation and illegal. The answer to the problem seemed to be appropriate legislation providing for their acquisition and the settlement of any legal claims of the road companies.13

[13. Assistant Attorney General to the Secretary of the Interior, 7 December 1891, in Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Relating to National Parks, 1872-1907 (Yosemite), RG 79, NA, 12-14.]

On 18 February 1892, Secretary of the Interior John Noble sent a letter to A. G. Speer, special agent of the General Land Office in San Francisco. In that communication Noble stated that the Interior Department wished to foster a system of roads and transportation and hotel accommodations that would make visitor excursions to the park as agreeable as possible. At the same time, the department would attempt to be as liberal as possible to all private interests as was compatible with the purposes of Congress in establishing the park.

To that end, Noble directed Speer to consult with Capt. Abram Wood as soon as possible and obtain information on the condition, origin, and right of franchise of all the toll roads within the park as well as on their convenience and use to the public. Noble also requested that Speer meet with the various owners and managers of the toll roads to enable them to make their claims to recognition by the Department of the Interior.

In the summer of 1892, Capt. John S. Stidger, a special agent from the General Land Office, and Maj. Eugene F. Weigel joined Speer and Wood in that endeavor, with Weigel, a special land inspector of the Interior Department, also detailed to investigate the condition of affairs in Yosemite Valley. On 24 September Speer was relieved of official duty and Captain Stidger directed to continue the work relating to the toll roads with Weigel and Wood. In his 3 October 1892 report to Noble concerning Yosemite Valley, Weigel noted that the toll roads in and outside of the park were very annoying to travelers and recommended that the federal government acquire all such roads within the limits of the national park.

On 21 October 1892 representatives of the four toll roads—the Big Oak Flat and Yosemite Road, the Coulterville and Yosemite Road, the Great Sierra Wagon Road, and the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Road—met Weigel, Wood, and Stidger at the U. S. Land Office in San Francisco and presented them with statements from the corporations owning those roads, showing their condition, franchise rights, length, cost, rates of toll, and so forth. In his report to Noble of 15 November Stidger suggested that the United States government follow the example set by the state of California and purchase and open to free use all the roads within the boundaries of Yosemite National Park. Congressional representatives from California and the Executive Committee of the Yosemite Board of Commissioners also made pleas to that end, citing federal money that had been appropriated for roads and bridges at Yellowstone National Park and at the National Military Park embracing the Chickamauga and Chattanooga battlefields.14

[14. Senators and Representatives in the U. S. Congress from California to the Honorable Hoke Smith, Secretary of the Interior, ca. 16 October 1895, in Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Relating to National Parks, 1872-1907 (Yosemite), RG 79, NA, 1-7.]

House bill 7872 and Senate bill 3675, relative to the purchase and opening to free traffic of the four private toll roads in Yosemite National Park and to the building of other necessary new roads by the government, were introduced in the Fifty-fifth Congress. The House referred the former to the Committee on Public Lands, which reported favorably on it and recommended passage by the House of Representatives. The pressure of business in the House was such that neither Senate bill 3675, which had passed the Senate, nor House bill 7872 could be reached, and neither was passed by the Fifty-fifth Congress.

A substitute measure, however, in the form of an amendment to the “Act making appropriations for sundry civil expenses of the Government,” passed on 3 March 1899. That provision, in addition to providing $4,000 as mentioned earlier for the protection of the park and for specific construction and improvement work, also provided that the Secretary of War expend some of the money to appoint three commissioners to examine and collect data on the existing toll roads; on new wagon roads from Yosemite Valley to Merced, Mariposa, and Tuolumne counties; on a new wagon road connecting the Tioga Road with roads in Mono or Inyo counties; and on a wagon road to Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Secretary of War Russell A. Alger appointed the requested Yosemite National Park Commission on 28 April 1899, composed of Col. Samuel M. Mansfield, Corps of Engineers, U. S. A.; Capt. Harry C. Benson; and J. R. Price, of the Department of Highways of the state of California. Just prior to the commencement of the commission’s work, Mr. Price ceased to be a member of the Department of Highways and retired from the commission. Joseph L. Maude, commissioner of highways of the state, succeeded him. The commission performed its work during the summer and fall of 1899 and reported to the Secretary of the Interior on 4 December.15

[15. The commission’s report was printed by order of the Senate as Senate Doc. 155, 56th Congress, 1st session. ]

The commission pointed out that up until 1890 little attention had been paid to the country surrounding Yosemite Valley. Now, however, the tolls demanded by owners of the only access routes restricted travel into the new national park. The government’s duty entailed either purchasing the existing roads or constructing new toll-free ones. If the latter course were chosen, the existing road owners would have to be compensated in some way, because the construction of free roads would divert all travel from the toll roads and would constitute practically a confiscation of the existing toll roads. It would be advantageous, anyway, the commission argued, for the government to own all entry roads into the park to ensure proper control of traffic.

The commission also found that the existing roads used for patrol purposes were not adequate for smooth communication between the troops guarding the park. The construction of additional roads would also lessen the cost of transportation of supplies to the troops and enable better fire control. Eliminating tolls on all the existing roads and constructing new ones would also enable visitors as well as the military to reach all sections of the park. Suggested new roads led: from the Tuolumne Soda Springs on the Tioga Road, along the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne, to the foot of Lyell Glacier; from the Mono Valley to the Tioga Road via either Mill Creek, Lee Vining, or Bloody canyons; from Tenaya Lake, on the Tioga Road, down Tenaya Creek Canyon to the floor of Yosemite Valley; and from Yosemite Valley, utilizing the existing road to The Cascades, west down the Merced River canyon. The latter road, providing access from the Mono Valley on the east to the San Joaquin Valley on the west, would be easier and faster than any existing routes and would remain open through the entire year. The road down Tenaya Creek Canyon would shorten the distance between Yosemite Valley and Soda Springs and avoid the high altitude of the Tioga Road at Snow Flat.

Since the establishment of Yosemite National Park in 1890, $8,000 had been appropriated out of the public treasury for its maintenance, half of this sum in 1898 and half a year later. The first $4,000 funded a special civilian detail to prevent trespassing by sheep and cattle within the park limits while the U. S. Cavalry, usually charged with that duty, fought in the Philippine Islands; the latter amount had been expended in defraying the expenses of the Yosemite National Park Commission. Californians felt that Congress should be more liberal in its appropriations for the development of Yosemite, commensurate with the state’s contributions to the public treasury. They recommended renewed efforts toward purchasing at fair value and eliminating tolls on the four toll roads into Yosemite and building the new road from Merced Falls to

|

Illustration 49.

Yosemite Valley floor, ca. 1900. Postcards published by Flying Spur Press, Yosemite, California. |

Illustration 50.

First automobile in Yosemite Valley, 1900. |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

[16. John T. McLean, A Brief Statement, Showing how properly California has kept the conditions of the trust upon which it accepted the grant of the Yosemite Valley. . . . How munificently the Nation, through Congress, has treated its other National Parks . . .; what undeserved neglect the Yosemite National Park has had . . .; and, a Plea That the same care and consideration should be given to The Yosemite Park. . . . (Washington: Globe Printing Company, 1900), 15-21, 26-28, in Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Relating to National Parks, 1872-1907 (Yosemite), RG 79, NA.

This statement was prepared by McLean and printed as an argument for appropriations by Congress to make the park toll roads free and for the construction of such new roads as were necessary to make all parts of the park accessible. It was first to be read at a meeting of the California congressional delegation held on 16 April 1900 and subsequently circulated among members of Congress in Washington and among state officers and members of the California press.]

With the publication of the commission’s report, and in line with the annual reports and official letters of various secretaries of the interior between the years 1892 and 1898 declaring it to be government policy that all roads traversing national parks should be free, the California congressional delegation decided to act. It determined to request sufficient appropriations to buy the private roads in the park and to build at least the proposed new road from Merced Falls up the Merced River canyon to Yosemite Valley. The California State Legislature, in an extra session, unanimously passed Assembly Concurrent Resolution, No. 2, introduced by the Committee on Roads and Highways, on 7 February 1900. That resolution, regarding appropriations for roads in and about Yosemite National Park, instructed the California congressional delegation in Washington to take whatever action it thought necessary to secure proper appropriations for the necessary improvements to the park in accordance with the report of the three federal commissioners.

1. State of California

a) Pavilion

During the 1901 season, the Yosemite commissioners built an open-air dance floor, or pavilion, on the riverbank near the Guardian’s office in the Old Village. Lighted by electricity, it served for all sorts of public functions, especially for the dancing socials held twice a week during the summer and fall.

b) Powerhouse

In 1902 the state built an electric light and power plant on one of the Happy Isles. The Yosemite commissioners managed the plant, which had cost about $30,000. The plant was housed in a permanent frame building. Water to run the operation was diverted from the river to the powerhouse through an imbedded iron pipeline. In the plant it turned against a pelton wheel with sufficient head to operate the system. The building had a concrete floor containing imbedded wooden beams to which were bolted the generators and the frames holding the pelton wheels. In 1905 the California state attorney general ruled that the electric light plant was a permanent fixture of the valley and that title thereto passed to the United States under the terms of the recession act.17

[17. U. S. Webb, Attorney General, to Hon. J. J. Lermen, Sec. of Comm. to Manage Yosemite Valley 23 July 1906, in Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Relating to National Parks, 1872-1907 (Yosemite), RG 79, NA, 6.]

2. Concession Operations

a) Wawona Hotel

Sometime prior to 1894, the Washburns erected “Little Brown,” a two-story cottage with cupola east of the main hotel. Early in 1891 they and J. J. Cook and his son formed the Wawona Hotel Company to manage the hotel and the farming, bartering, and other commercial interests associated with it. About 1899 construction began on “Long Brown” (present Washburn Cottage) east of Long White (Clark Cottage).

b) Cosmopolitan Bathhouse and Saloon

After the Cosmopolitan ceased to operate in the 1880s, the premises served various purposes. The front of the building became the office and living quarters of the Guardian of the valley, occupied in turn by Walter E. Dennison, Mark L. McCord, Galen Clark, and Miles Wallace. The final two Guardians under the state—John F. Stevens and George T. Harlow, from 1899 to 1906, lived in a new building slightly east of the Old Village general store.

During Clark’s second administration as Guardian, 1889 to 1897, his office in the Cosmopolitan’s front room functioned as a club or lounge for the men of the village and occasional visitors. There, gathered around a large table and huge stove, they passed the time catching up on valley affairs. Occasionally assemblies, such as school programs and community parties, took place in another large room near the center of the building. (Even in Smith’s time, his saloon had frequently been the site of local gatherings.)

The excess space in the Cosmopolitan building not needed by the Guardian provided extra sleeping quarters in connection with the Sentinel Hotel and also served as the hotel barroom and barber shop. A section in the rear of the building became a small bunkhouse for workmen. The bunkhouse, barroom, and barber shop were collectively referred to as the “Collar and Elbow.” After the Guardian’s office and living quarters moved to the new headquarters building, the front part of the Cosmopolitan functioned variously as a post office and express office, and served whatever other needs arose.18

[18. Degnan to McHenry, 17 November 1954.]

c) Camp Curry

In 1899 two teachers came to Yosemite who had begun using their summer vacations to manage camping tours of the West. David A. and Jennie Foster Curry had settled in Redwood City, California, in 1898. Having become enamoured of mountain country through classes in nature lore taken under David Starr Jordan at Indiana University, they had for several seasons arranged and conducted tours through Yellowstone Park, in which small parties moved from place to place with camp equipment and baggage.

In 1899 they decided to spend the summer in Yosemite and establish a camp there. With seven sleeping tents and a larger one to serve as dining room and kitchen, and with the assistance only of a cook and students from Stanford University working for room and board, the Currys originated an idea in tourist service that revolutionized hostelry operations in Yosemite and other national parks. Their first camp stood on the site of present Camp Curry.

The success of this hotel/camp arrangement was immediately apparent. What began as a summer camping operation to accommodate a few paying guests turned into much more than that as more than 290 people registered the first year, necessitating the addition of eighteen more tents. Dependency on the railroad and a two-week round trip by wagons and mules to Merced for supplies made operation of the camp difficult, but the reasonable rates and informal hospitality brought patrons back year after year. Evening campfire entertainments proved popular from the beginning, gradually becoming more structured with regular entertainment programs. During one of the first summers of operation, Curry revived McCauley’s firefall tradition on a regular basis. By 1901 a large dining room and rustic office had been built. The Currys adopted the distinctive Adirondack rustic style for their earliest permanent buildings. Characterized by stick and bark panelling, the style later appeared on the Yosemite Valley Railroad Station at El Portal and on the railroad’s office in Yosemite Valley. The original registration office built in 1904 is now used as a lounge. Postal facilities have also been incorporated on the north side. Its rustic style is characterized by unpeeled logs, vertical posts, and horizontal beams, with strips of natural cedar bark in a herringbone pattern as a decorative element.

d) Degnan Bakery

By 1894 John Degnan was cultivating Lamon’s upper orchard and the family lived in a small frame house near the site of Lamon’s original cabin for a few months. After the family moved back to the Old Village, John continued to work for the state and do odd construction jobs for the hotels and stage companies. In 1898 Degnan built a new house on the site of the old J. J. Westfall meat market. In the bakery attached to the rear of their house, Bridget prepared bread for sale in a brick oven that yielded 100 loaves per baking. The Degnans sold these and other baked goods through the store.19

[19. Degnan to Hubbard, 24 February 1956.]

e) Fiske Studio

In May 1904 fire destroyed George Fiske’s Yosemite home, resulting in the loss of its furnishings in addition to his lenses, cameras, and entire collection of West Coast negatives. Fiske rebuilt, although it is unclear whether in the same area, north of the Four-Mile trailhead and about one mile from the Old Village, or in the Old Village, where a 1920 map shows a residence referred to as Fiske’s house.20

[20. Ansel F. Hall, Guide to Yosemite: A Handbook of the Trails and Roads of Yosemite Valley and the Adjacent Region. (Yosemite National Park: National ‘Park Service, 1920), 9.]

f) Foley Studio

D. J. Foley established a print shop and photographic studio in 1891 and published a souvenir paper titled The Yosemite Tourist beginning in that year. He also sold Foley’s Yosemite Souvenir and Guide. His building, known as the Yosemite Tourist Printing Office and Studio, stood just west of the superintendent’s office. (After his death, Mrs. Foley continued the business into the 1940s.)

g) Jorgensen Studio

Artist Chris Jorgensen first came to Yosemite Valley in 1898 and camped two summers before building his first cottage—a studio and residence—on the north bank of the Merced River in 1900. He built a one-story, one-room log structure, “the bungalow,” in 1903 on the opposite side of the river from the Sentinel Hotel and a short distance above the bridge. He also had a barn and storehouse on his land. This new residence had a wood shingle-covered gable roof, with the front decorative gable end projecting ten feet beyond the front wall of the cabin. Its walls consisted of peeled logs in alternating tiers and contained an original stained glass window. Jorgensen, a noted painter, maintained a seasonal residence and studio in the valley for twenty years.21

[21. In 1962 the Park Service razed the earlier Jorgensen studio and residence and moved the later bungalow to the Yosemite Pioneer History Center, believing it to be the studio building. It is, therefore, the Jorgensen home that has been preserved rather than his studio. Mary Vocelka, Research Librarian, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, Comments on the Historic Resource Study, 8 January 1987, 1.]

h) Boysen Studio

While the valley was under state control, J. T. Boysen received a concession to conduct a photographic studio. He had come to the valley about 1898 and had supplied photos of the valley and of the Mariposa Big Tree Grove to the World Exposition at St. Louis and at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland. His first two years he conducted his business in a tent, but when the commissioners ruled that there would be no more tents along the main avenue in 1900, he built a small studio of unfinished lumber west of the superintendent’s office between D. J. Foley’s Studio and Salter’s store. Boysen concentrated on photographing the Mariposa Grove and the Yosemite Indians. The Yosemite Park and Curry Company bought his studio in 1943.

i) Best Studio

In the spring of 1901 landscape painter Harry C. Best came to Yosemite, and, after marrying a young lady he had met in the valley, applied for a permit from the Yosemite commissioners to sell photographs and paintings. In the season of 1902 the couple set up a tent studio near the government pavilion in the Old Village.

j) Studio of the Three Arrows

In the winter of 1902, Harold A. Taylor, who had arrived in the valley the preceding April as assistant to Julius Boysen, and Eugene Hallett, agent for the Santa Fe stage line, formed the Hallett-Taylor Company and took over the business and building of Oliver Lippincott. They named their place the ‘’studio of the Three Arrows,” because Taylor’s family crest centered around three arrows, and, in addition, the name seemed an appropriate motif for the valley because of its Indian history. The photographic business stood across the street from the Degnan home and bakery.

3. Sierra Club

a) Creation of Club

Although John Muir and other conservationists had been highly delighted by the preservation of the Yosemite high country through establishment of the national park, they continued to worry that forces bent on the exploitation of the fledgling national parks would continue to agitate for mineral, timber, water, and homestead rights. They began to think in terms of some sort of unified organization to combat those aggressions and lobby for preservation of the wilderness. At the same time, a growing number of people in California started to express an interest in hiking and exploring the Sierra. What they needed was an organization to provide maps and material related to mountaineering. It seemed logical, ultimately, for the two groups with such similar interests to join and form a mountaineering club—a Sierra club—to work toward the preservation of California’s natural wonders, especially those of the Yosemite region.

On 4 June 1892 those individuals formed the Sierra Club, with John Muir as president, to explore the mountain regions of the Pacific Coast, to publish reliable information concerning that area, and to enlist the cooperation of the people and government in preserving the forests and other natural features of the Sierra Nevada. It took a while for the club to get going. Despite its periodic meetings and publication of a Bulletin beginning in 1893, interest in it gradually began to wane. In 1897 the Sierra Club asked that it be allowed to establish headquarters in Yosemite Valley where it could provide maps and other data to visitors. The club also was considering laying out short trips and arranging excursions to the high country. A year later it reached an agreement with the Board of Yosemite Commissioners that the latter would repair the Sinning cottage on the opposite side of the road from the Sentinel Hotel for the Sierra Club’s use as a general information bureau. The club then furnished the house and provided publications, maps, and collections relating to the High Sierra. The club and the board of commissioners equally bore the salary for a summer attendant, who would man the bureau for the club and also assist the Guardian by directing campers to campgrounds and by dispensing 2 general information on the valley to visitors in the Guardian’s absence.22

[22. J. N. LeConte and Charles A. Bailey to the President and Board of Directors of the Sierra Club, 9 June 1898, in “Notes and Correspondence,” Sierra Club Bulletin II, no. 4 (June 1898): 239.]The idea of sponsoring mountain excursions seemed the most likely prospect for reinvigorating the club. The idea received only minimal consideration, however, until the arrival of William E. Colby on the scene. In 1900 Colby, a lawyer and enthusiastic hiker who eventually became a leader in the Sierra Club, envisioned leading organized outings into the High Sierra. President Muir agreed with the suggestion and made Colby chairman of the Outing Committee. They scheduled the first official Sierra Club Outing for Tuolumne Meadows in the summer of 1901. As plans got underway, a new member, Edward Parsons, joined the club. A successful businessman and accomplished mountaineer, he was already a member of several prestigious mountaineering groups when he joined the Sierra Club. Immediately becoming a member of the Outing Committee, he and Colby led hundreds of hikers into the mountains over the next several years. Colby served forty-four years as secretary of the club and two as president. For sixteen years he served as an active member of the Yosemite Advisory Board.

That first Sierra Club outing, consisting of rugged day-long expeditions into the surrounding mountains from a base camp in Tuolumne Meadows, initiated a special kind of social and instructive institution in the Sierra Nevada. Club members returned year after year for the popular trips and developed life-long friendships amid the active social programs and the serious study of nature pursued through reading assignments and natural history lectures by Muir and other experts around the evening campfire. The trips were intended not only to attract new members and provide a pleasant recreational experience, but also to instill in club members an appreciation of the beauty and inspiration of the mountains and a desire to defend them from all threats of spoliation. Soda Springs, where the Sierra Club established a campground and later a lodge, became the center of field activities for Sierra Club members. The club sponsored various summer and winter activities in that area, including hiking, sightseeing, cross-country skiing, and mountaineering. The Sierra Club’s outings had a strong impact on backcountry use, providing the impetus for additional trail building and map work.

In general, the Sierra Club aimed at the promotion of both a recreational and aesthetic appreciation of the High Sierra country, but it was especially protective of Yosemite. Its genuine concern for the future of that great preserve became apparent during the battles over recession of the Yosemite Grant and development of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. The Sierra Club’s dedication to the preservation of Yosemite National Park would be severely tested during that last controversy. The club’s leading members, although disheartened by the outcome of the issue, nevertheless in the course of the entire affair acquired a knowledge of political processes and skills in political maneuvering that would prove invaluable in the future. The club itself acquired a reputation that provided it with considerable influence and ensured its participation in important policy-making decisions on conservation matters related to the public domain.23

[23. Jones, John Muir and the Sierra Club, 168-69. After John Muir’s death in 1914, the Sierra Club became primarily a social organization, losing some of its established ties with mountaineering. After 1916 it often aligned itself with the National Park Service, two of its illustrious members being Californians Stephen Mather and Horace Albright. It tended to refrain, however, from active participation in conservation battles by the mid-1930s and into the 1940s, although it reemerged during the 1960s in the forefront of the modern American conservation movement. Stephen Fox, John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement (Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown -and Company, 1981), 214, 272.]

b) LeConte Lodge

On 6 July 1901 Joseph LeConte, the eminent scientist and noted professor of geology and natural history at the University of California, an early director of the Sierra Club who spent much of his time studying the Sierra and the geology of Yosemite, died at Camp Curry in Yosemite Valley.

The directors of the Sierra Club appointed a commission, consisting of Professors A. C. Lawson and William R. Dudley, Dr. Edward R. Taylor, Elliott McAllister, and William E. Colby, to decide upon an appropriate memorial. The committee decided that, rather than building a conventional memorial, it would be more appropriate, based on LeConte’s active and useful life, to erect a lodge to serve as a reminder of LeConte and also be of direct benefit to others.

Large groups of Professor LeConte’s friends contributed to the $5,000 fund necessary for construction, including many prominent San Francisco merchants; the student body, alumni, and faculty of the University of California; members of the faculty of Stanford University; mining engineers; geologists; LeConte’s relatives and personal friends; and members of the Sierra Club. Although they raised several thousand dollars, a few hundred were still lacking. As a result, the directors of the Sierra Club levied an assessment on club members of $1.00 each. LeConte’s widow provided the last $200 needed in the form of twenty-eight gold nuggets that had been given Dr. LeConte on his golden wedding anniversary by several former pupils in South Africa.

The LeConte Memorial Lodge, finished in September 1903 at a cost of $4,714 and dedicated on 3 July 1904, had a picturesque and unique character that attracted great interest. The architect, John White, donated both his plans and his time to the work. The finished structure, containing a variety of design features, nonetheless blended harmoniously with its environment. Located behind Camp Curry and under the walls of Glacier Point on a gentle slope against a background of trees, the lodge entrance provided a fine view of Half Dome. The structure became the Sierra Club’s headquarters in Yosemite Valley during the summers and contained a portion of the club library as well as maps and photographs. A custodian provided information to visitors on the club and surrounding mountains from May to July.

Local rough-hewn granite formed the foundations, walls, and chimney of the structure. As much of the rock’s weathered surface as possible faced the exterior. Broad granite steps led to a “Dutch” entrance door. The main reading room measured thirty-six by twenty-five feet with a huge granite fireplace at one end surrounded by bookcases and window seats. Interior roof beams were left exposed and rough finished. The unique reading room table, measuring nine by five feet, had a heavy top supported by two sections of the unbarked trunk of a large yellow pine.24

[24. William E. Colby, “The Completed LeConte Memorial Lodge,” Sierra Club Bulletin 5 (1904-1905), no. 1 (January 1904) (San Francisco: The Sierra Club, 1950), 66-69.]

4. U. S. Army

a) New Camp Buildings

The U. S. Army used the present site of the A. E. Wood Campground on the South Fork of the Merced River near Wawona as its main camp and administrative headquarters from 1891 until 1907, when the troops moved into Yosemite Valley. Captain Abram Wood established the first army post on 17 May 1891 and called it “Camp near Wawona.” Its designation changed to “Camp A. E. Wood” in 1901.25 In the beginning, tents and other temporary structures, which were usually destroyed by campers and other trespassers during the winter, sheltered the troops and their equipment. A desperate need existed for a permanent building for housing and to allow storage of equipment so that it would not have to be transported back to San Francisco each year. Little construction took place the first few years, although troops did construct a horse shed in 1901.

[25. Register of Letters Received, 1912, and Letters Received, 1912-13, RG 393, Records of the U. S. Army Commands (Army Posts), NA. Camp A. E. Wood became “Camp Yosemite” when it moved into Yosemite Valley in May 1907. The army abandoned the latter post 31 October 1913.]

As stated earlier, in 1904, in the vicinity of the camp, the soldiers built a footbridge across Big Creek, which is no longer extant. A simple two-plank-wide structure, it provided access to the arboretum, described below. Another bridge in course of construction by the troops that season crossed the South Fork of the Merced River. Troops also added an office/storeroom and corral that year.

In 1905 the War Department allotted $3,000 for the improvement of Camp A. E. Wood. This funded installation of a water supply system and the construction of numerous buildings, including kitchens and mess halls, commissary and quartermaster storehouses, a stable extension, and a bathhouse. The army purchased lumber for the sides and roofs, but the soldiers obtained the construction timbers from nearby forests. During the year the troops also built a packtrain stable, a laundry, and a wagon shed, the material for those buildings obtained through the seizure of several thousand shakes illegally cut on government land. The troops quartered in floored Sibley tents, and enjoyed ranges and other equipment necessary for their comfort during a protracted stay.26

[26. Report on Yosemite National Park, under “National Parks and Reservations,” in Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1905. Report of the Secretary of the Interior and Bureau Offices, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1905), 165.]

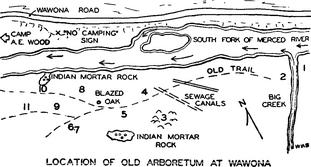

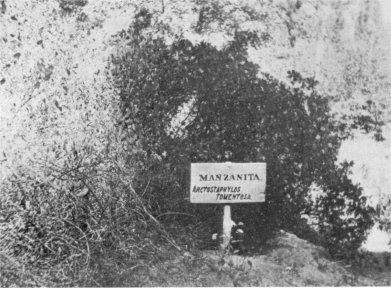

b) Arboretum

Major John Bigelow, Jr., acting superintendent of Yosemite National Park, constructed an arboretum and botanical garden in 1904 close to Camp A. E. Wood. Bigelow described the arboretum as bounded on the north by the south side of the South Fork of the Merced River, on the east by property of the Wawona Hotel, on the south by the southern boundary of the park, and on the west by a line running north-south from a point between the two bridges at Camp Wood and the southern boundary of the park. It covered an area of roughly 75 to 100 acres. On its eastern boundary, Big Creek, which furnished drinking water to the army camp via a flume and pipe, ran northward into the Merced River. An old trail followed up the right bank of Big Creek about one-half mile to where the water entered the flume, while another old trail connecting the Wawona Hotel and the camp passed through the arboretum from east to west.

Bigelow had guideposts erected to assist visitors in finding their way to and through the arboretum and several seats constructed to provide opportunities for sitting and studying the various plantings. He intended to fence in the area to keep out loose stock. Labels and signs adorned the trees and marked the plants. The signs consisted of one-inch plank, double coated on both sides with light-brown paint, which bore English and Latin names in dark brown letters 1% to 2 inches high. The labels were nailed to the trees, and the signs nailed to posts that were painted light brown and charred where they entered the ground. White metal tags measuring about 3 inches by 3/4-inch bore the names of the flowers. Bigelow put First Lieutenant and Assistant Surgeon Henry F. Pipes in charge of the arboretum, who had no particular training as a botanist but evinced great enthusiasm for the project.

By late fall 1904 troops had improved the arboretum by posting more signs and labels, opening up paths, erecting signposts and seats, trimming trees, and removing dead wood. Thirty-six trees and plants had been marked, as well as two prehistoric Indian bedrock mortar sites within the arboretum acreage, and a number of plants had been identified for transplanting in the arboretum.

The order instituting the arboretum designated that an officer be detailed to take charge of it, assisted by a noncommissioned officer and one private detailed on special duty. Their responsibilities included guarding the grounds against trespassers; marking samples of the various species of trees, flowers, and plants found in the arboretum with both their English and Latin names; and planting in the arboretum, as far as practicable, other varieties of interesting plants found within the park boundaries.27

[27. Appendix, Exhibit A, in Bigelow, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” 23 September 1904, in Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1904, 395-97. ]

Bigelow, very interested in natural history and especially in trees, intended that the arboretum develop into a prominent feature of the park and some day be supplemented by a building serving as a museum and library. This accorded with his belief that one of the essential purposes of the Yosemite forest reservation was to provide a museum of nature for the general public free of cost, to display not only trees, but everything associated with them, in nature, including animals, minerals, and geological features.

|

Illustration 51.

Wawona arboretum, 1904. Footbridge over Big Creek at left, bench built onto trees at right. |

[click to enlarge] |

| LOCATION OF OLD ARBORETUM AT WAWONA |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 52.

Wawona arboretum, 1904. Sign on post identifies “Manzanita.” Photographer unknown. |

[click to enlarge] |

The year after the arboretum’s establishment, however, the boundary change of 7 February 1905 excluded the patented land on which it lay, on the south side of the Merced River, from the park. Acting Superintendent H. C. Benson at that time attempted to gather and store for future use within the park as many of the identifying signs as possible, although some had already been knocked down by surveyors for a projected railroad into the region. (See discussion of Fresno Traction Company later in this chapter.) In 1929 Ranger J. N. Morris rediscovered the arboretum, neglected for years, and found twenty trees still bore labels. The area became part of the park again with the Wawona Basin addition of 1932.

The arboretum project remains significant as an initial attempt to interpret for visitors and other interested people the botanical features of Yosemite National Park, sixteen years before Dr. Harold C. Bryant began the nature-guide service in Yosemite that became the nucleus of the present naturalist interpretive program of the National Park Service. The arboretum complex included the first self-guiding nature trail in the National Park System.

At its height, the arboretum complex consisted only of the two bridges mentioned, several rustic benches, the labels that identified plantings, and the interpretive signs that guided visitors. The flat area to the east, between the hillside and the Merced River, became the site of a sewage treatment facility for the Wawona Hotel, which considerably changed the appearance of the area. Sewage canals were placed prior to 1951, and a sewage treatment pond with a pump, a pumphouse, and a spray field was later installed on the hillside above. Today there are few traces left of the arboretum. A few signs can still be found with some searching, although the bulk of them have been removed or weathered away, as have the benches built for contemplation of the plantings. The trails are now overgrown and almost impossible to distinguish.28

[28. Other sources of information on this interesting enterprise are J. N. Morris, “An Old Nature Trail is Found Near Wawona,” Yosemite Nature Notes 9, no. 3 (March 1930): 17-18; Sargent, Wawona’s Yesterdays, 18; and O. L. Wallis, “Yosemite’s Pioneer Arboretum,” Yosemite Nature Notes 30, no. 9 (September 1951): 83-85.]

1. Continuing Charges of Spoliation of Yosemite Valley

On 22 September 1890 the U. S. Senate adopted a resolution that the Secretary of the Interior report to the Senate as to whether the lands turned over to the state of California in 1864 had been spoliated or otherwise diverted from the public use stipulated by the grant. If so, the Secretary was to determine what steps would be necessary and proper in order to ensure the prevention of further spoliation and the return of the valley to public use.

Congress made no appropriation to enable the Secretary to prosecute his inquiries, and so he pursued the problem primarily through correspondence. He sent letters of inquiry to persons of good repute who he thought probably knew details about the situation in Yosemite. He perused reports and printed statements on the subject, as well as photographs of the valley.

The general concensus of the people asked for opinions seemed to be that

1) there had been a general and indiscriminate destruction of timber in the valley, for building material, to prepare land for plowing, to open up views, and for fuel;

2) from one-half to four-fifths of the valley had been fenced with barbed wire and planted in grass or grain, confining, travel to narrow limits between the fences and the cliffs;

3) many rare plants had been destroyed by pasturing animals and plowing;

4) the management of the valley had fallen into the hands of a monopoly, with no competition permitted for hotel accommodations, transportation, or animal fodder;

5) the only land available for grazing was used by stock of the stable and transportation men so that no grazing lands existed for the mounts of visitors;

6) the high country had been abandoned to sheepherders, whose fires had damaged trees and shrubs, and to their flocks, which had eaten the grasses and herbage down to the bare dirt; and

7) the Big Tree Grove had been severely damaged by fires, with little effort made by the commissioners to extinguish them.