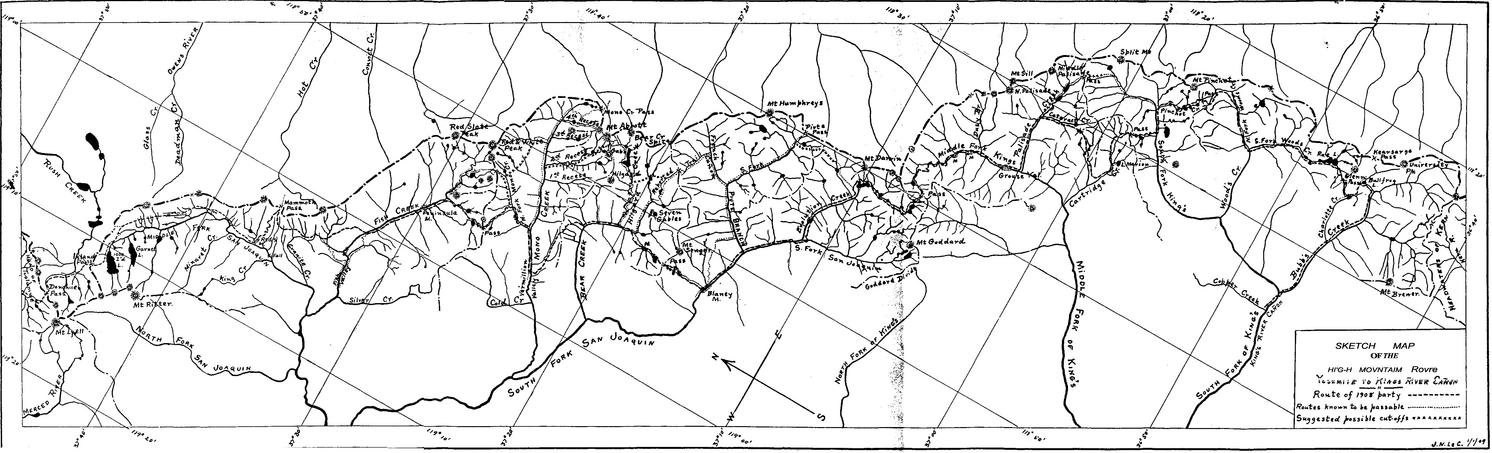

Sketch map of the High Mountain Route, Yosemite to the King’s River Canyon, 1908.

From LeConte, “The High Mountain Route Between Yosemite and the King’s River Canon,” Sierra Club Bulletin 7, no. 1 (January 1909).

[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Resources > Chapter IV: Administration of Yosemite National Park, 1905-1915 >

Next: 5: NPS 1916-1930: Mather Years • Contents • Previous: 3: Cavalry 1890-1905

A. The Army Moves Its Headquarters to Yosemite Valley 413

B. Trails, bridges, and Roads 414

1. Trails and bridges 414C. Buildings and Construction 443a) General Trail and bridge Work 4142. Roads 425

b) John Muir Trail 419a) El Portal Road 425

b) Status of Roads in 1913 430

c) Road and Trail Construction Required of the City of San Francisco 431

d) Initiation of Auto Travel in Yosemite 433

e) Effects of Auto Travel in the Park 437

f) The Federal Government Acquires the Tioga Road. 439

g) The Big Oak Flat Road Becomes Toll Free 443

1. Army Camp 4433. Park General 451

2. Yosemite Village 446

a) Schools 451D. Campgrounds 458

b) Powerhouse 456

c) Miscellaneous 456

d) Wood-Splitting plant 457

e) Fire Lookouts and Patrol cabins 457

1. The U. S. Army Becomes involved in Business Concessions 461F. Patented Lands Again Pose a Problem 481

2. Concession Permits in Operation During That Time 462

3. Camp Curry Continues to Grow 470

4. The Camp Idea Expands to Other areas 472

5. The Washburn interests 472

6. The Yosemite Transportation Company 477

7. The Yosemite Valley Railroad Company 478

8. The Shaffer and Lounsbury garage 479

9. The Desmond Park Service Company 479

1. Timberlands 481G. Insect and Blister Rust Control 494a) Lumber interests Eye Park Timber Stands 4812. Private Properties 488

b) Congress Authorizes Land Exchanges 483

c) The Yosemite Lumber Company 484

d) The Madera Sugar Pine Company 488a) Foresta 488

b) McCauley ranch 489

c) The Cascades (Gentry Tract) 490

d) Tuolumne Meadows (Soda Springs) 490

1. Beetle Depredations 494H. The Hetch Hetchy Water Project Plan Proceeds 496

2. White Pine Blister Rust 495

1. The Garfield Permit 496I. Completion of the Yosemite Valley Railroad 513

2. Antagonism to the Project Continues 497

3. The City of San Francisco Begins Acquiring Land 498

4. A New Secretary of the Interior Questions His Predecessor‘s Actions 500

5. The Raker Act 501

6. Construction Begins 505

7. General Character of the System 506

8. Elements of the Hetchy Hetchy System 507a) Hetch Hetchy Railroad 507

b) Sawmills 509

c) Lake Eleanor Dam 512

d) Hetch Hetchy Dam 512

1. Change in Administration of the Parks 518

2. Proposal for a Bureau of National Parks and Resorts 519

3. Establishment of the National Park Service 521

The first army headquarters in Yosemite National Park had been established near Wawona because the state of California still controlled the more logical site—Yosemite Valley—and state officials had made it abundantly clear that they did not want army troops permanently encamped in the valley. In fact, according to former park supervisor Gabriel Sovulewski, the Yosemite commissioners forbade army patrols entering the valley from Wawona from camping farther up the valley than Bridalveil Meadow and strictly limited their movements in the valley, off or on duty.1 With the recession of the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove to the United States, Acting Superintendent Maj. H. C. Benson proceeded to the valley on 22 June 1906 with one troop of cavalry, leaving only an outpost at Wawona.

The War Department allotted $1,500 for the erection of new buildings on the present site of Yosemite Lodge and the re-erection of all the buildings that had been located at Wawona during the summer of 1905. In addition, the army built a forage house, saddle rooms for each troop, grain sheds, an orderly room for each troop, and an adjutant’s office. All stables, one for each troop and one for pack mules, had to be built anew. The army camp occupied all the ground west of the Yosemite Creek bridge as far as Rocky Point, including Leidig Meadow.

1. Trails and Bridges

a) General Trail and Bridge Work

Appropriations for improvement and repair of park facilities allowed construction of several trails and bridges during the year 1906. Thomas H. Carter of Wawona contracted for all the work, which included:

a six-mile trail from Hetch Hetchy Valley to Tiltill Valley;

a trail from the crossing of Rancheria Creek at its upper bridge to a point five miles up Rancheria Mountain toward “The Sink”;

a two-mile trail from “The Sink” to Pleasant Valley;

a twelve-mile trail from Pleasant Valley to Benson Lake, along the south side of the lake to its east side, then north to Kerrick Canyon;

a one-mile trail along the north side of Tiltill Valley connecting a trail entering on the southeast with one leaving for Lake Eleanor on the northwest;

three miles of trail from Lake Vernon to Tiltill Valley;

a 3-mile trail along the north side of Hetch Hetchy Valley, extending from the bridge at the upper end of Hetch Hetchy to a point half a mile below Falls Creek;

a fourteen-mile trail in Kerrick Canyon to the point where the trail to Stubblefield Canyon leaves it, then across Thompson and Stubblefield canyons to Tilden Lake; and

bridges over Falls Creek in Hetch Hetchy Valley, over Falls Creek just below Lake Vernon, and over Eleanor Creek within one mile of Lake Eleanor.2

[2. Report on Yosemite National Park, 196-97, and Benson, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” in Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1906, 656-57.]

In 1907 Carter constructed a four-mile trail from Tilden Lake into Jack Main Canyon; a new trail from Hog Ranch to Hetch Hetchy Valley replacing the old steep and rocky one; and a trail along the north side of that valley.3 Also sometime during 1907 to 1908 Superintendent Benson ordered Register Rock cleared of its grafitti.

[3. H. C. Benson, Major, 14th Cavalry, Acting Superintendent, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” 30 September 1907, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1907. Administrative. Reports in 2 volumes. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907), 561.]

In 1908 Paul Seagall placed new pegs on the Half Dome route. The Sierra Club supplied the money for a new cable, the end of which Lawrence Sovulewski carried to the top. During the 1908 season, Carter constructed trails from Rancheria Mountain, via Bear Valley, to Kerrick Canyon, and from there, via Slide Canyon, to Matterhorn Peak, connecting with existing trails. The northern part of the park appeared now well supplied with trails, except for the area between Lake Eleanor and Twin Lakes. Also that year the army oversaw replacement of the Pohono Bridge in Yosemite Valley and repair of the iron bridge near the Sentinel Hotel. Day labor repaired the bridge over the Merced River above Kenneyville (Upper Bridge). Louis C. Hill, a supervising engineer, recommended that in the future all bridges constructed be arches of either reinforced concrete or granite, that style being much more satisfactory from both a maintenance and aesthetic point of view.4

[4. H. C. Benson, Major, 14th Cavalry, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” 30 September 1908, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1908. Administrative Reports in 2 volumes. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908), 426-27, and Appendix A, “Roads in Yosemite National Park,” Louis C. Hill, Supervising Engineer, to Hon. James R. Garfield, Secretary of the Interior, 10 December 1907, in ibid., 436.]

No new bridges were built during the 1909 season, but the El Capitan Bridge received a new floor and the bridges over the Merced near Camp Curry and over the Tuolumne in Hetch Hetchy Valley underwent repairs. By 1909 the following bridges crossed the Merced River and Tenaya Creek in Yosemite Valley:

Pohono Bridge (steel), 100 feet,

Sentinel Hotel Bridge (steel), 96 feet,

El Capitan Bridge (wood), 100 feet,

Stoneman Bridge (wood), 92 feet,

Upper Bridge (wood), 100 feet,

Power House Bridge (wood), 86 feet,

Tenaya Creek Bridge (wood), 85 feet.

The U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, believing that all the bridges except Pohono would have to be replaced within a few years, also recommended that they be replaced by stone arch bridges, which would be almost indestructible, more appropriate to the park setting, and “an adequate monument to represent the American Government in architectural work in its national park.”5

[5. Appendix A, “Report on Roads, Trails, and Engineering Structures,” A. R. Ehrnbeck, 1st Lieut., Corps of Engineers, 4 October 1909, in Wm. W. Forsyth, Major, Sixth Cavalry, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” 15 October 1909, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1909. Administrative Reports, jjn 2 volumes. Volume I. Secretary . of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910), 434.]

By the 1910 season, all the important trails outside of the valley had been repaired and those from Tamarack Flat to Aspen Valley and from Hetch Hetchy Valley to Lake Eleanor shortened and improved. A new trail from above Mirror Lake to Tenaya Lake had been completed nearly to the top of the cliff in Tenaya Canyon. Bridge construction in 1910 included a new wagon bridge over the Merced River at the power plant, a new footbridge to Happy Isles, and a new wagon bridge over Cascade Creek on the Yosemite-EI Portal road. By this time names had been formalized for several of the largest bridges in the valley, including Sentinel Bridge over the Merced River near the Sentinel Hotel; Stoneman Bridge across the Merced between Kenneyville and Camp Curry; Clarks Bridge over the Merced near the old orchard in the east end of the valley; Tenaya Bridge over Tenaya Creek; and Secretary Bridge over the Merced near Happy Isles.6

[6. Wm. W. Forsyth, Major, Sixth Cavalry, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” 15 October 1910, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1910. Administrative Reports in 2 Volumes. Volume II. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing ‘Office, 1911), 464-65.]

In the fall of 1911 bridge work included replacement of the log bridge over Yosemite Creek near Camp Yosemite and repair of the foot suspension bridge over the Merced near Camp Ahwahnee, badly damaged by high water and floating logs in the river. The heavy floods of the spring and early summer had also carried away part of the bridge over the Tuolumne River in the Hetch Hetchy Valley.7 Trail work also continued. Originally, to reach Merced Lake, hikers had to ascend the Sunrise Creek Trail and cut north of Bunnell Cascade before dropping down to Merced Lake. In 1911 a new trail followed along the Merced River to Bunnell Point and crossed over its tip to Merced Lake, saving four miles.

[7. Wm. W. Forsyth, Major, Sixth Cavalry, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” 15 October 1911, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal. Year Ended June 30, 1911. Administrative Reports in 2 volumes. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1912), 589.]

During 1912-13, trail construction included completion of: a trail branching off of the Mirror Lake-Tenaya Lake trail at Snow Creek and proceeding to North Dome and Yosemite Point; a trail from Tenaya Lake to Clouds Rest, passing between Clouds Rest and Sunrise Mountain, via Forsyth Pass; a spur trail from the Forsyth Pass trail to the junction of the Merced Lake and Sunrise trails; a trail from McClure Fork to Washburn Lake; and a trail from the junction of the Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak trails, via White Wolf and Harden Lake, to Hetch Hetchy Valley; as well as changing of the Sunrise trail from its junction with the old Clouds Rest trail to its junction with the Merced Lake trail.

Bridges constructed during 1912-13 included two horse and pedestrian bridges over the Merced River between Merced and Washburn lakes, one over the Merced River above Nevada Fall, and another over 11lilouette Creek; a wagon bridge over Tenaya Creek on the valley floor; two footbridges on the Happy Isles trail; and a small footbridge over a branch of Yosemite Creek on the Lost Arrow trail.8 Also a contractor, Oscar Parlier of Tulare, California, began construction of three reinforced-concrete arch bridges on the road passing by the foot of Bridalveil Fall. The government constructed the spandrel walls and roadway involved.

[8. Gabriel Sovulewski, Park Supervisor, “Report of the Park Supervisor,” 15 October 1913, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1913. Administrative Reports in 2 volumes. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1914), 732, 734. The McClure Fork of the Merced River became Lewis Creek in 1944. See discussion in Chapter V, fn. 8.]

Labors during the 1914 season consisted primarily of improving trails in the south and southeastern parts of the park. About three miles of new trail constructed from Washburn Lake south to the Lyell Fork of the Merced River opened up a beautiful section along the main canyon of the Merced. A trail that ran from the Wawona ranger station along the South Fork of the Merced for several miles before bearing north to the main Buck Camp trail at the Buck Camp ranger station was named for Ranger Archie Leonard. Leonard had supposedly first blazed the trail in the early 1900s during his scouting and guide work in the park for the U. S. Army troops. A sixty-foot-span foot and horse bridge of wood and steel trusses, known as the Register Rock Bridge, was constructed over the Merced River below Vernal Fall.9

[9. Gabriel Sovulewski, Park Supervisor, “Report of the Park Supervisor,” 27 September 1914, and David A. Sherfey, Resident Engineer, “Report of Resident Engineer,” 30 September 1914, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1914. Administrative Reports in 2 volumes. Volume II. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1915), 730, 735.]

New trails constructed during 1914 and 1915 included: the Donohue Pass trail—from the junction of Ireland Creek and the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne River to Donohue Pass; the Buck Camp trail—from Illilouette Fall, along Illilouette and Buena Vista creeks, joining the Buck Camp trail at Johnson Lake; the Merced Pass trail—from its junction with the Mono Meadow trail to Merced Pass; and partial relocation of the Merced Lake trail near Merced Lake. In addition, the California Construction Company of San Francisco constructed a new El Capitan Bridge in 1915, a combination steel and wood truss structure with a span of 87-1/2 feet.10

[10. Gabriel Sovulewski, Park Supervisor, “Report of Park Supervisor,” 30 September 1915, and David A. Sherfey, Resident Engineer, “Report of the Resident Engineer,” 30 September 1915, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1915. Administrative Reports in 2 Volumes. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1916), 923, 926.]

b) John Muir Trail

Theodore S. Solomons, a mountain-climbing enthusiast and one of the founding members of the Sierra Club, first conceived of a pack trail across the southern High Sierra paralleling the main crest as a young boy of fourteen. He arrived in Yosemite in 1892 to begin the first of a series of organized explorations of the region to find a practicable route. Early reconnaissance work, lacking detail, had previously been undertaken during 1864 and 1865 by Professor William H. Brewer of the California Geological Survey and his assistants. Later John Muir had explored many of the upper canyons of the San Joaquin and King’s rivers. Solomons was primarily working, however, in areas of the Sierra whose main features remained completely unknown. During his 1892 trip, Solomons concentrated chiefly on the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River to the mouth of the South Fork. Other trips in 1894 and 1895 further explored the upper regions of the San Joaquin River basin and basically established the route that now constitutes the northern half of the John Muir Trail.

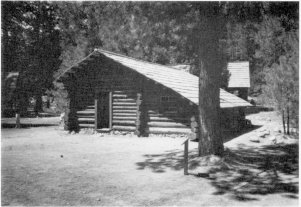

In 1887 Joseph N. LeConte, professor of mechanical and hydraulic engineering at the University of California, and nephew of geologist Joseph LeConte, began making regular trips into the Sierra making scientific observations and triangulating major peaks. In 1893 he compiled all data available on the portion of the Sierra Nevada adjacent to King’s River and published a map. A larger and more inclusive one published by the Sierra Club in 1896 showed the results of explorations to date. After Solomons’s groundbreaking, other explorers subsequently penetrated new areas and established new landmarks which facilitated perfecting of the route. In 1898 LeConte followed Solomons’s route south from Yosemite and pioneered a way to King’s River Canyon. Because the southern part of the route avoided the High Sierra at its most beautiful point, however, it was still not considered the true high mountain route that Solomons had striven for.

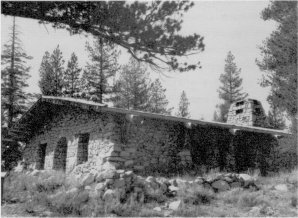

LeConte continued working out and piecing together bits of the route until he finally completed the desired 228-mile route in 1908. His 1909 map outlines in detail most of the present John Muir Trail.

By that time the areas at either end of the route had been well mapped, making the whole region known, although as yet inaccessible to most people. Yosemite National Park already had a decent trail system, but most of the rest of the proposed route lay in national forests. The northern part consisted primarily of Indian paths and sheep trails, while farther south various agencies, including the U. S. Forest Service, Fresno and Tulare counties, and the Sierra Club had built or financed improvements on trails in various sections. It still remained difficult to pass from one region to another and most of the trail was only generally indicated on maps.

Meanwhile, in 1901 the Sierra Club had begun its annual summer Outings. During 1914 a member, Meyer Lissner, suggested that the state of California undertake a program to improve and construct High Sierra trails to make that area more accessible. He proposed that the club formulate a program to seek appropriations for trail development. The club immediately appointed a committee to develop the idea. Meanwhile, John Muir, leader of the Sierra Club for many years, died, and William Colby, secretary of the club and the man drawing up the bill, inserted a provision to name this proposed trail along the Sierra crest the John Muir Trail, in honor of the man who so enthusiastically explored and publicized the beauties of the High Sierra.

On 28 January 1915 State Senator William J. Carr introduced the bill in the California Senate and Assemblyman F. C. Scott introduced it in the lower house. Governor Hiram Johnson signed the bill into law on 17 May 1915, and the legislature appropriated $10,000 for the work. State Engineer William F. McClure, required by the bill to select a practical route from Yosemite to Mount Whitney along the crest of the Sierra, made two field inspections to establish the exact route. It was decided, after several conferences with representatives of the Sierra Club and Forest Service, that the trail would begin at Yosemite Valley and ascend to Tuolumne Meadows;

|

Illustration 56.

Sketch map of the High Mountain Route, Yosemite to the King’s River Canyon, 1908. From LeConte, “The High Mountain Route Between Yosemite and the King’s River Canon,” Sierra Club Bulletin 7, no. 1 (January 1909). |

[click to enlarge] |

thence across Donohue Pass and Island Pass to Thousand Island Lake and past the Devils Postpile, Fish Creek, North Fork of Mono Creek, Vermilion Valley, Bear Creek, Blaney Meadows, Evolution Creek, Muir Pass, Grouse Meadow, Palisade Creek, upper basin of the South Fork of Kings Riveg,, Pinchot Pass, Woods Creek, Rae Lake, Glen Pass, Bullfrog Lake, Bubbs Creek, Junction. Pass, Tyndall Creek, and Crabtree Meadows to Mount Whitney.11

[11. Walter L. Huber, “The John Muir Trail,” Sierra Club Bulletin 15, no. 1 (February 1930): 40.]

McClure asked officers of the Forest Service to supervise the trail’s construction, which they did without charge. Initial work began in August 1915 on connecting completed portions of the trail and would continue for several more years as the state legislature provided additional appropriations.12

[12. Roth, Pathway in the Sky, 25, 27-28, 38, 41-42. Also see Theodore S. Solomons, “A Search for a High Mountain Route from the Yosemite to the King’s River Canon,” Sierra Club Bulletin 1, no. 6 (May 1895): 221-37; Joseph N. LeConte, “The High Mountain Route Between Yosemite and the King’s River Canon,” Sierra Club Bulletin 7, no. 1 (January 1909): 1-22; Huber, “John Muir Trail,” 37-40; Theodore S. Solomons, “The Beginnings of the John Muir Trail,” Sierra Club Bulletin 25, no. 1 (February 1940): 28-40.]

2. Roads

a) El Portal Road

In connection with their proposed railroad up the Merced, the Yosemite Valley Railroad Company had offered to build a wagon road from El Portal connecting with the Coulterville toll road. Upon completion, the road would become a public highway. The company would construct those few miles, at an estimated cost of $80,000, if Congress made no similar appropriation for such a project. When Congress did not, the company planned to proceed on construction and have both its railroad and a wagon road in operation for the 1907 travel season. To complement that endeavor, the Department of the Interior allotted $8,000

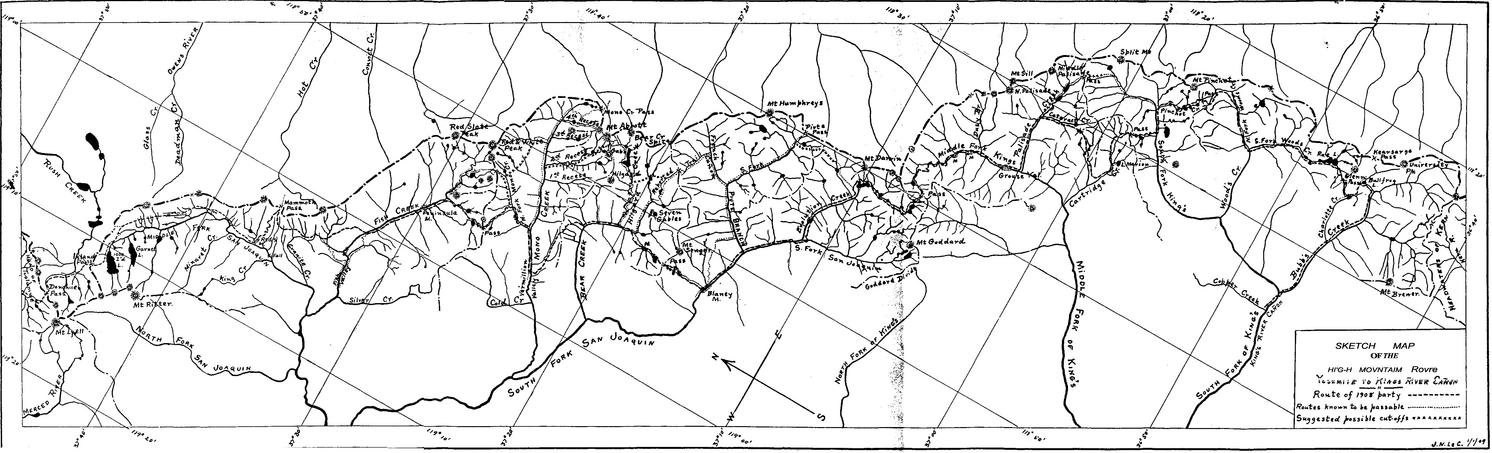

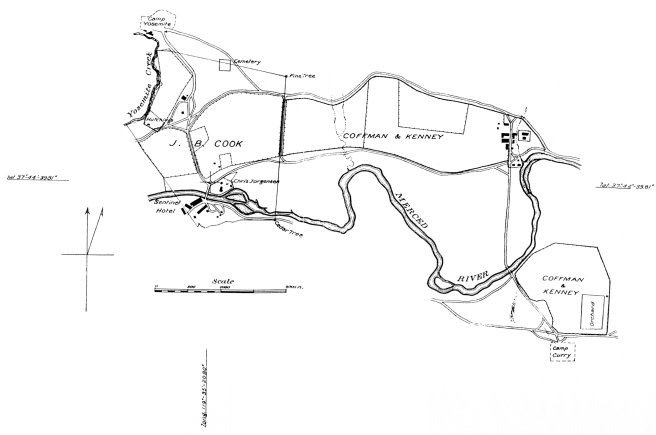

|

Illustration 57.

Map of Yosemite Valley showing roads and projected revisions, 1912-13. From Automobile Club of Southern California Road Department Report on Condition of Roads into Yosemite Valley, 1912, in Central Files, RG 79, NA. |

[click to enlarge] |

Although the new wagon road facilitated travel into the valley from El Portal, it remained an uncomfortable journey. The majority of park visitors followed this route, which led from the terminus of the Yosemite Valley Railroad along the north bank of the Merced River for ten miles before crossing to the south side of the river over the Pohono Bridge and proceeding on to the Sentinel Hotel. The first ten miles of the road remained for several years extremely rocky, narrow, and tortuous. In 1908 Acting Superintendent Benson complained about the deplorable road conditions into and around Yosemite Valley: “The one great drawback to the visitor’s pleasure is the fact that he is driven over rough roads so dusty that when he arrives at his destination his dearest friend could not recognize him.”13 Benson stressed that the valley roads needed widening, macadamizing, and watering.

[13. Benson, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1908, 425.]

The first actual roadwork the federal government performed after recession of Yosemite Valley involved improvement of the El Portal road. In 1909 work began on macadamizing it from the El Capitan Bridge to the Sentinel Hotel along the south side of the Merced. A year later that portion had been graded and culverts installed. Traveling conditions over the El Portal-Old Yosemite Village road improved in 1910 with installation of a sprinkling system with water for the new road section, provided by two 5,000-gallon tanks installed between Camp Ahwahnee and the El Capitan Bridge. During the fall of 1912 and summer of 1913, grading and macadamizing proceeded on the El Portal road in the area of Camp Ahwahnee.

The work of widening the lower sections of the road began on 10 May 1913. By the first of October almost two miles had been widened from ten to twenty-five feet to incude a guard wall, ditch, and eighteen-foot roadbed. Construction work involved drilling and blasting through the large boulders and solid granite formation through which the road wound. Rock debris from this effort was thrown down the slope toward the Merced River.

b) Status of Roads in 1913

In 1913 the government owned forty-six miles of road within Yosemite National Park, including nineteen on the floor of Yosemite Valley, on both sides of the Merced River from the Pohono Bridge to Mirror Lake; the nine miles of the El Portal road, from the Pohono Bridge to the western park boundary; four miles of the Wawona Road, from the valley floor to Fort Monroe on the southern rim; four miles of the Big Oak Flat Road, from the valley floor to Gentry’s on the valley’s northern rim; and ten miles of roads in the Mariposa Big Tree Grove. A lack of planning had resulted in an excessive number of unattractive roads in the valley that intruded on the landscape.

In addition, approximately 106 miles of wagon road existed in the park, either toll roads or otherwise privately owned, including 19 miles of the Coulterville Road, whose franchise expired about 1920; 10 miles of the Big Oak Flat Road, whose franchise expired 20 January 1921; 45 miles of the Tioga Road, whose franchise expired 8 January 1934; and 32 miles of the Wawona-Glacier Point Road, whose franchise expired 16 November 1927.

These roads were all in poor condition in 1913. Prior to the 1920s, most road work involved maintenance and repair with only minor improvements. Until the roads were paved, park crews accomplished renovation work each spring with horse teams and hand tools—filling ruts and washouts, spreading gravel, and sprinkling the roadbed. Exclusion of autos from the park from 1907 to 1913 contributed in large part to the continuing deterioration of park roads. The increased use of the roads after that time eventually applied the necessary pressure that resulted in resurfacing and realigning of existing routes and construction of new ones. Travel over roads into the valley had dropped to such an extent after construction of the Yosemite Valley Railroad that the various road companies found it no longer profitable to maintain them. Consequently, the Coulterville and Tioga roads had been practically abandoned, although the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company continued to collect tolls on the Wawona Road, keep it in repair, and operate a horse-drawn transportation line over it. Visitors also continued to use the Big Oak Flat Road to some extent.

Another road, built by cattlemen and others living or working in the area, led from the Tioga Road to Hog Ranch via Ackerson Meadow. That private road branched off the Tioga Road about one mile from Carl Inn, outside the park. Only a ford existed across the Middle Fork of the Tuolumne River until about 1915, when a bridge was completed and approaches built on each end. That road became an important link in the trip to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir that the park transportation system inaugurated in 1918, although Congress did not provide funds and authorize its maintenance by the National Park Service until 1922.

c) Road and Trail Construction Required of the City of San Francisco

M. M. O’Shaughnessy, city engineer for the city of San Francisco and chief architect of the Hetch Hetchy Project, appeared before the Public Lands Committee in 1913 and offered to spend one million dollars on roads and trails for the benefit of visitors to Yosemite as the Secretary of the Interior might direct.14 The act of Congress approved 19 December 1913 granting the city and county of San Francisco certain rights-of-way in, over, and through public lands in Yosemite National Park and Stanislaus National Forest specified that the grantee would construct on the north side of the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir site a scenic road or trail (to be determined by the Secretary of the Interior) above and along the proposed lake to a point designated, and a trail leading from that road or trail to Tiltill Valley and to Lake Vernon and a road or trail to Lake Eleanor and Cherry Valley via Miguel Meadow. Likewise it directed the city to build a wagon road from Hamilton along the most feasible route adjacent to its proposed aqueduct from Groveland to, Hog Ranch and into the Hetch Hetchy dam site. The city of San Francisco rebuilt approximately four miles of that road—a typical mountain track used only by horse-drawn vehicles—eliminating the steep grades so that it could be used to truck in supplies and equipment for the Hetch Hetchy Project prior to construction of the Hetch Hetchy Railroad. Congress also requested a road along the south slope of Smith Peak from Hog Ranch past Harden Lake to a junction with the Tioga Road.

[14. E. P. Leavitt, Acting Superintendent, Yosemite National Park, to the Director, National Park Service, 9 November 1927, in Box 84, Hetch Hetchy, “Gen’l 1926-1927,” in Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 2-9, 14.]

The purpose of the road or trail along the north edge of the reservoir and of the trail from that route to Tiltill Valley and Lake Vernon was to allow accessibility to the large park area in the Rancheria Mountain district that would become isolated when construction of the Hetch Hetchy reservoir flooded all the trails up the valley previously leading into that area.

The city could build other roads or trails through the public lands necessary for its construction work subject to the approval of the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior. Those roads and trails would be assigned free of cost to the federal government, which would be reimbursed by the city for maintenance costs. The money received would be kept in a separate fund and applied to the building and maintenance of roads and trails and other improvements in Yosemite and other national parks in the state.

d) Initiation of Auto Travel in Yosemite

In 1900 Frank H. and Arthur E. Holmes had driven a Stanley Steamer over the Chowchilla Mountains to Wawona. Over the next few years, state officials allowed the few cars who ventured in free access to Yosemite Valley. That goodwill evaporated after 1906 when Yosemite Valley became part of Yosemite National Park and the volatile Major Harry C. Benson, acting superintendent, began overseeing park affairs. Irritated by driver disobedience of the strict regulations he had instituted for auto travel, and dismayed by plans for an impending trip to the valley by the Oakland Automobile Dealers Association, Benson secured approval from the Secretary of the Interior in 1907 to ban autos from Yosemite Valley. Lobbying efforts by various automobile associations to reopen the main roads of the park to motorists reached their peak in 1912, when a joint delegation representing the Automobile Club of Southern California, the Los Angeles Motor Car Dealers’ Association, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, and other large organizations made an appointment to meet with Secretary of the Interior Walter L. Fisher in the park to personally appeal their case.15

[15. Richard G. Lillard, “The Seige and Conquest of a National Park,” American West 5, no. 1 (January 1968): 67-68; “To Seek Opening of Yosemite to Motorists,” 7 October 1912, in Los Angeles Real Estate Bulletin and Building News, Box 3, Washburn Papers, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

It was at this mid-October 1912 second National Parks Conference involving park superintendents, concessionaires, the Secretary of the Interior and other officials, and several interested groups and individuals, that John Muir was called upon for his opinion as to whether autos should be allowed in the parks. At that point Muir, with the same vision that characterized his views on the environment, pronounced that the era of automobiles had arrived. He believed that autos would allow more people to enter the valley and that no group of men could prevent them from becoming the means of travel for the future.16 All roads in and about Yosemite in 1913 had been built for horse-drawn vehicles and not designed as possible auto roads. Opposition from several quarters arose to the entrance of autos into the national parks, principally on the grounds that the unsuitable roads would cause many accidents between autos and horse-drawn conveyances.

[16. “Yosemite Retrospect and Prospect,” speech given by William E. Colby, Camp 14 Anniversary Program, 30 June 1939, in Separates File, Y-4, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

On 30 April 1913, Secretary Franklin Lane rescinded the order barring automobiles from Yosemite National Park, stating that

This form of transportation has come to stay, and to close the park against automobiles would be as absurd as the fight for many years made by old naval men against the adoption of steam in the navy. . . . I want to make our parks as accessible as possible to the great mass of people.17

[17. “Lane Opens Up Yosemite Park to Automobiles,” Fresno (Calif.) Republican, 30 April 1913, in Miscellaneous Facts File, Wawona Road, Y-20d, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

The immediate question from interested parties in nearby counties concerned the number of roads to be opened to autos. The Interior Department decided to first open only the Coulterville Road—a route in such poor condition that even horse-drawn vehicles rarely used it. The department feared that if all roads opened at the same time without proper regulation, the resulting number of accidents could seriously retard the entire process. Eventually it would open all roads to auto travel, but only gradually and after careful study.

At the time of Secretary Fisher’s conference at Yosemite Valley in October 1912, he concluded that it would not be safe for autos to enter Yosemite Valley over the Wawona Road, although they could safely travel to the rim of the valley over the Wawona-Chinquapin-Glacier Point road. The Madera County Chamber of Commerce particularly desired to have the Madera-Wawona road opened to auto traffic as soon as possible and determined to ask for a federal appropriation to improve the road from near Fort Monroe to the valley floor. It feared that the initiation of auto traffic to the park over other roads would adversely affect Madera County’s economy and depreciate the value of the Wawona toll road.

On 5 August 1913, the Interior Department published regulations governing the admission of automobiles into Yosemite National Park. The inadequate surfaces of the park roads and their many narrow stretches and abrupt turns that complicated auto travel necessitated strict rules regarding the acquisition of permits, the hours of entrance and departure, and time and speed allowances for reaching destinations. Autos could approach the park only by the Coulterville and Big Oak Flat roads. Those traveling on the latter had to turn west at Crane Flat and get on the Coulterville Road to enter the valley. Once on the valley floor, cars were restricted ‘to the road north of the Merced River.18

[18. Lewis C. Laylin, Asst. Secretary of the Interior, “Regulations Governing the Admission of Automobiles Into the Yosemite National Park,” 5 August 1913, Box 3, Washburn Papers, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

The Coulterville Road opened to automobiles on 23 August 1913, and during that season the army established additional outposts for checking auto traffic at Merced Grove and Cascade Creek. By the summer of 1914, an allottment of $2,500 allowed repair work on the Wawona Road between the valley floor and Fort Monroe. After completion of that work, establishment of a telephone checking system, and the publication of regulations for their use, the Wawona Road and the road to the Mariposa Big Tree Grove also opened to auto traffic, on 8 August 1914. The Big Oak Flat Road opened on 16 September of that year. Cars remained restricted in usage by a variety of regulations until 1916, when the glorious era of horse and stagecoach rides to Yosemite ended.

The memoirs of early auto visitors to the park seem to focus mostly on the narrowness and steepness of the roads. Because the time restrictions on travel within the park often left people stranded at park entrance stations after closing hours, rangers learned to keep extra supplies of cots and canned goods on hand. They also had to care for pets, which were not allowed in the park, until their owners’ return and retain any firearms brought in.

In February 1913 the Madera, Yosemite, Big Tree Auto Company was organized and replacement of stagecoaches by buses began. In 1915 this company, under agreement with the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company, formed the “Horseshoe Route” stage line running from Raymond to Mariposa Grove, Wawona, Glacier Point, and Yosemite Valley. Auto travelers to Yosemite who wished to see as much as possible in one trip often availed themselves of the Horseshoe Route. It entered the valley via the Mariposa Big Tree Grove and Inspiration Point and left it by way of El Portal. The Horseshoe Route stage line ultimately sold out to the Yosemite Park and Curry Company in 1926.

During the automobile era, J. R. Wilson devised another interesting way to see the park. In 1913 he constructed a six-mile road of eight percent grade, costing $40,000, that ran behind the Del Portal Hotel in El Portal and on to the Merced and Tuolumne groves. Referred to as the Triangle Route because it led from El Portal at one corner to the Merced and Tuolumne groves at another, and to Yosemite Valley at the third, it passed through extremely scenic country, which made it a favorite with tourists. As an added thrill, autos could pass through the hollowed-out tunnel in the Dead Giant Tree in the Tuolumne Grove. From the Big Trees the route led to Yosemite Valley via the Big Oak Flat Road. After crossing the Merced River over El Capitan Bridge, autoists could turn west and head back to El Portal. Wilson had a permit to operate three auto stages over this road during the 1913 season.

A. B. Davis, who had a permit for that route in 1915, also obtained a permit in July 1914 to construct the four-mile “Davis Cut-off.” Davis, one of the promoters of the Foresta subdivision, conceived of this route linking Foresta with Crane Flat as an additional way to attract buyers. That route began northwest of Big Meadow and ran north beyond its junction with the Coulterville Road to Crane Flat and the Big Oak Flat Road, enabling tourists to visit Foresta, tour the Tuolumne Grove, and then descend into Yosemite Valley. Davis also organized the Big Trees Auto Stage Company.19

[19. Sargent, Yosemite’s Rustic Outpost, 22. Sargent states the road was built in the early summer of 1914. Other sources have stated a year later.]

On 1 June 1915 the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company replaced its old horse-drawn stages with an automobile service that transported tourists between the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Village. This new, faster mode of transportation, however, also enabled visitors from the valley to visit the grove and return in one day without having to stay overnight at the Wawona Hotel. On 16 July 1915 rental auto service began on the valley floor to carry tourists from camp to camp and around the valley and to make special trips over the Tioga Road. One of the reasons for the service, in addition to restricting the volume of traffic on the poor valley roads, was to pacify tourists who were not allowed to run their personal autos around the valley floor. The Department of the Interior had decided upon that policy because the average tourist’s unfamiliarity with the valley’s turnouts, sharp curves, trail junctions, and stage schedules increased the chance of accidents.

e) Effects of Auto Travel in the Park

Few people, especially in the Interior Department, realized the impact the auto would have on the national parks, indeed on the country as a whole. The auto enabled a new class of tourists to visit the park—those who had never before been able to take a vacation, who often lacked any knowledge or appreciation of America’s unique scenic areas, and who had little education or understanding of how to properly enjoy such areas: “For the first time, the under-privileged family of small means, by the use of an automobile was able to take advantage of our great national playgrounds and at last the original conception of the National Park movement was on a fair way to being realized.”20

[20. Paper delivered by Donald Tresidder before a meeting of the Conservation Forum in Yosemite National Park, 1935, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

Even in the early days of the auto, congestion became common at the park entrances, along its roadways, and in parking areas. On summer evenings, cars solidly lined the valley roads as their owners gathered to watch the firefall. Although cars alleviated some of the pressure on valley meadows by lessening the need for cultivation of stock feed, enabling those areas to develop into scenic attractions, they still managed to inflict severe damage by driving and parking on them. Campgrounds overflowed into Stoneman and Leidig meadows and later even onto the Ahwahnee Hotel grounds. Because Yosemite Valley contained a high concentration of scenic values within a small area, the influx of motor travel threatened havoc on its scenic integrity. Trampled grass and shrubbery, scattered litter, traffic congestion, air pollution, the lack of adequate traffic control, overcrowded facilities, and unhappy visitors finally forced park officials to realize they needed a management plan for growth and development to ensure maximum enjoyment of the area with minimum damage to the resources.

Although the Park Service did over the next few years reassess its objectives and develop a group of experts in landscaping, engineering, sanitation, traffic control, and education who studied the new problems and formulated plans for the proper use and preservation of the national parks, some problems created by auto travel remain to plague park administrators. By the late 1960s, the ever increasing visitation to Yosemite, brought about by the popularity of auto travel and improved road surfaces, raised traffic congestion again to unacceptable levels, causing the Secretary of the Interior to note as late as 1969 that “the private automobile is impairing the quality of the park experience.”21

[21. George B. Hartzog, Jr., “Clearing the Roads—and the Aii—in Yosemite Valley,” National Parks & Conservation Magazine (August 1972): 16.]

Little realizing the problems that lay ahead of them, officials in the fledgeling National Park Service only gradually began to see that the arrival of the auto would drastically change visitation numbers and patterns in Yosemite and the course of park development. For many Americans, auto touring became a recreation in itself, prompting the need for better road access to popular sites and some method of traffic control. Because people could get to the park faster, they often intended to stay longer. If they planned on staying two weeks, they usually wanted something to do besides look at scenery. Most of them also desired all the amenities they could get at home. As the park provided more accommodations, more restaurants, better food and dry goods services, and other support facilities, it also required more employees who needed housing and various community services, such as schools and hospitals. In an attempt to provide these, as well as a variety of recreational and educational experiences, the federal government and the concessioners embarked on a period of construction and development that would markedly change both the visitor experience in Yosemite and the historic landscape.

f) The Federal Government Acquires the Tioga Road

The outstanding legacy of the Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Company was its wagon road, which increased the accessibility of the Tuolumne Meadows region. It never carried rich silver shipments, and the new heavy machinery purchased for use in the Sheepherder tunnel that should have passed over it was instead sold at auction in San Francisco after the mine closed.

As previously alluded to, upon the wagon road’s completion, its owners obtained a fifty-year franchise to charge toll for travel over it between Tuolumne and Mariposa counties. They never erected collection gates for tolls, however, and tourists, stockmen, and army patrols freely passed over the road. After the mining company ceased operations, it remained open, but received only periodic maintenance. It remained passable despite occasional fallen trees, washouts, and numerous rough spots. There was increasing sentiment, however, for its purchase by the federal government because of its importance as a patrol road. Some even believed that the road already belonged to the government by default because it had never been a toll road and appeared to have been literally abandoned by the owners for years. But had it been?

The story of the changes of ownership of the Great Sierra Wagon Road is as complicated as that of the Tioga Mine itself. William Swift obtained the road toll franchise from Road Superintendent William C. Priest at the same time he acquired the properties of the Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Company. Upon Swift’s death, his brother Rhodolphus acquired both the mine properties and the road, which remained the property of his heirs until 1915.

During that period the law firm of Wilson and Wilson handled business pertaining to the road for its owners. The attorneys believed that the light travel on the road was responsible for its eventual neglect and argued that if the road were completed down the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, traffic would increase and the owners would resume collecting tolls to finance maintenance work. In the meantime, campers and other heavy users of the road performed necessary repairs such as bridge replacement. The attorneys claimed, nonetheless, that the owners had regularly expended some money on repairs and annually paid their property taxes. Despite the controversy over the road’s status, the federal government never pursued its threat of condemnation and the owner’s lawyers continued to maintain that the government had no claim to the road except by purchase.

The opening of Yosemite to automobile traffic raised again the subject of acquisition of the Tioga Road, which, since 1890 and the establishment of the national park, had remained a private enterprise. Attempts through the years to get Congress to appropriate money to purchase the right-of-way had failed. The Interior Department, therefore, remained unable to repair the road and open it to tourist use. On 21 January 1915, a Californian, Stephen T. Mather, became Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, with jurisdiction over the national parks.

One of the Mather’s most notable projects at Yosemite involved the purchase of the Tioga Road. In casting about for a project to lead off his administration of the parks, Mather turned to Yosemite, which, in view of two international expositions scheduled for the state of California, was destined to receive increased visitation. Because the old mining road constituted the only potential auto route across the Sierra, its ownership and improvement by the federal government would be extremely popular with Californians and economically beneficial both to the state and the federal government.

The Tioga Road’s owners still held the right-of-way and toll privileges handed down from the original owners. Mather, therefore, decided to acquire the outstanding but valid toll road rights from the Swift estate. Aided by leaders of the Sierra Club, especially William Colby, Mather managed to contact the owners of those rights, who eventually offered to sell them. Interested parties east of the mountains, meanwhile, undertook to secure state cooperation to improve the road up Lee Vining Canyon from Mono Lake to the park line. As noted earlier, recommendations had previously been made for a route up the eastern slope of the Sierra to connect with the Great Sierra Wagon Road, replacing the treacherous horse trail down Bloody Canyon that connected the Tioga Mine with Mono Valley. A new route to the east had been touted as not only facilitating mine haulage from the mountains but also providing accessibility to Yosemite Valley and the High Sierras. In 1902 construction had begun on the Tioga Pass-Lee Vining route, and by 1905 all but five miles east of the pass had been finished. Although that stretch was finally completed by 1908, the Tioga Road lay in such a state of disrepair that the trans-Sierra route as a whole was practically impassable.

Mather and his friends ultimately raised the funds necessary to acquire the Tioga toll road rights. Mather spent several thousand dollars of his own money on the purchase, while philanthropists, civic groups, the Sierra Club, and private individuals provided the rest. Mather then discovered that no law existed under which the Secretary of the Interior could accept a gift of this kind. The chairman of the Appropriations Committee turned down Mather’s request to Congress for authority to accept gifts for the benefit of the national parks. Ultimately Senator James Phelan and Congressman William Kent of California succeeded in securing the requested authority to accept gifts for Yosemite. Mather transferred formal title to the Tioga Road and the toll rights and easements to the federal government on 10 April 1915. As soon as Congress accepted the Tioga Road, Mather allocated national park funds to repair bridges, culverts, and the roadbed. Park crews rushed work through the summer. By mid-July the Tioga Road was passable, and opened to auto traffic on 28 July 1915.

Horace M. Albright, then an administrative clerk in the office of Assistant Secretary of the Interior Mather, years later recalled the drive up to Tioga Pass for the dedication ceremony marking the opening of the road. What later provided a humorous anecdote, at the time constituted a hair-raising experience probably endured by many early travelers over the old, single-lane Tioga Road:

Will L. Smith was the driver of the car—a Studebaker, I think—in which three of us rode; Mr. McCormick [vice-president of the Southern Pacific Railroad] in front with Will Smith; Emerson Hough [Saturday Evening Post writer] and I in the rear seat, Hough on the outside; that is, overlooking the gorge, and I behind McCormick. Will Smith had been over the road many times and knew every turn, but we did not know this. He wanted us to see everything so he would describe scenes for us, even rising in his seat to point them out and sometimes turning around and pointing back, but never stopping the carl Whenever he did this, I would open the car door and put my foot on the running board, so when the car went over I possibly might fall on the road’s edge. Mr. Hough would be right on top of me ready to fall out with me. About the third time this happened, Hough said hoarsly in my ear, “Damn this scenery-lovin’ S. O. B.”22

[22. Horace M. Albright, “Horace Albright Recounts Opening of Tioga Road,” Inyo Register (Bishop, Calif.), 15 June 1961. See Keith A. Trexler, The Tioga Road: A History, 1883-1961, rev. 1975, 1980 (Yosemite National Park: Yosemite Natural History Association, 1961), for a comprehensive history of the road and its construction.]

g) The Big Oak Flat Road Becomes Toll Free

Another important event took place in July 1915 when Tuolumne County purchased the Big Oak Flat Road leading into Yosemite Valley for $10,000 with the intention of making it toll free. It gave the portion from the park boundary to Gentry’s to the federal government. After the state and county repaired their portion of the old highway by regrading and eliminating sharp curves and steep grades, the trip to Yosemite over that route became much easier. Assistant Secretary Mather then announced that the portion of that road within the park would also be repaired. The federal government had formerly declined to spend money on its improvement as long as private parties held any part of the road.23 The government also established a checking station at Gentry’s and one on the valley floor.

[23. Leon J. Pinkson, “Tuolumne Secures Road to Yosemite,” San Francisco Chronicle, 27 June 1915.]

1. Army Camp

An inspection report on Camp Yosemite in 1909 noted that its buildings, of the most temporary character, proved suitable for occupancy only during the summer months. The troops and officers quartered in wooden-floored tents. Soldiers performed most camp construction work. The army stables had only roofs, their sides and ends open to the weather. Saplings cut near the camp formed the framework of the stables and of two large storage tents. Two dining rooms exhibited similar construction. Only the headquarters, the bakery, the quartermaster and commissary storehouses, two company kitchens, the blacksmith shop, the guardhouse, and the officers’ mess had been enclosed. Those buildings had walls of rough pine boards and battens, shingle and shake roofs, rough floors, unfinished interior walls, and half-sash stationary windows. They stood on temporary wooden foundation sills. The Chief Quartermaster of the Department of California recommended that if Camp Yosemite continued in that locality, more substantial buildings be constructed. Any new buildings should be fashioned entirely of wood, with native mountain pine used for the exterior and interior finishes, with roofs and sides covered with unpainted shakes.24[24. Robert R. Stevens, Chief Quartermaster, Department of California, Memo for Adjutant General, Department of California, 28 June 1909, in Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence, 1890-1914, RG 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, NA.]

The War Department in 1911 began erection of two temporary barracks, two lavatories, and seven frame cottages at Camp Yosemite, as well as installation of a water and sewer system. These were still built to the old army summer residence standards and of the same design formerly found in tropical army posts. The buildings were completed and accepted 20 December 1911.25

[25. Forsyth, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year. Ended June 30, 1911, 591-92, 596.]

By 1912 day labor under the supervision of the resident engineer had built four small cottages “of an appearance appropriate to the environment” for the resident engineer, a clerk, and two electricians. Frame buildings adjacent to the military camp, they sat upon concrete foundations and had electric lights and plumbing. The army also erected a reinforced concrete magazine for the storage of high explosives on the north side of the Merced River opposite Bridalveil Meadow.26 During the 1913 season, the acting superintendent lived in the officers’ clubhouse at the army camp.

[26. Wm. W. Forsyth, Major, First Cavalry, “Report of Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” 30 September 1912, in Reports of the Department . of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1912. Administrative Reports in 2 volumes. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913), 665, 669-70. The U. S. Army built residences 1, 2, 4, and 5 now within the Yosemite Village Historic District in 1911-12. The army barracks later served as the original Yosemite Lodge buildings. None of those structures remain. Joe Desmond also acquired tent platforms left by the army and used them in constructing the floor of the Yosemite Lodge dining room. Although frame army buildings were not unusual, Forsyth’s remark that they harmonized with the surroundings shows a continuing awareness of the principles that would later characterize the Park Service’s rustic architecture program.]

The need for adequate medical service in Yosemite Valley had been an issue for many years. In 1880 the Yosemite commissioners had urged that a doctor reside in the valley throughout the year and requested an appropriation for his income. The state legislature made no such allotment, however, and for many years Mariposa provided the nearest medical service unless a doctor happened to vacation in the valley during the summer. The army surgeons accompanying the cavalry troops during the period of army administration often also served the public. In 1912 the army constructed a temporary two-story, board-and-batten hospital building at Camp Yosemite. Commanded by an officer of the Medical Corps, the hospital admitted civilians during the tourist season. After troops withdrew from the park in 1914, the War Department authorized a civilian doctor employed by the Interior Department to practice medicine in the facility.

During the summer of 1915 two San Francisco physicians and surgeons opened the hospital building for the practice of medicine and the sale of drugs under authority of the Department of the Interior. The old War Department building was slightly remodeled and provided with a new operating room. Despite the small staff, accident victims and sick cases could be adequately cared for. This facility served as the valley hospital until 1929.

2. Yosemite Village

Acting Superintendent Benson, in his 1908 report to the Department of the Interior, described the status of buildings in Yosemite Village. By that year the valley contained forty-six buildings, all of them frame except for the stone LeConte Memorial Lodge. The buildings comprised the residences, barns, stables, and outbuildings used by the concessioners and the Department of the Interior. The barns and stables appeared to be in good shape. Benson thought all the valley residences unsightly, except for John Degnan’s house, and unsuited to the valley. The park supervisor, Gabriel Sovulewski, lived in the log cabin that J. M. Hutchings had built forty years earlier and that appeared in danger of collapsing. The hotels looked old and dilapidated, while the park superintendent’s frame office, the most recently constructed building in the valley, comprised a patched-over but still serviceable structure moved in from another locality. “The village, so called, has grown up since 1900, and resembles the temporary houses built for a county fair more than the residences and offices of a government institution,” Benson complained.27

[27. Benson, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1908, 431.]

In 1910 workers completed an attractive cottage designed to replace Park Supervisor Sovulewski’s log cabin residence. After Army headquarters moved to Yosemite Valley, Acting Superintendent Benson requested that Gabriel Sovulewski, employed by the Quartermaster Department in San Francisco, report for duty in Yosemite Valley as park supervisor, the man who would work with the troops during the summer and continue to tend to park management and operations during the winter months. Sovulewski arrived on 12 August 1906 and, as a year-round resident, was housed (or at least cooked his meals) in the old Hutchings cabin, an uncomfortable domicile showing the wear and tear of years of neglect. It was razed in 1910 with construction of Sovulewski’s new residence, the first one built in the valley by the Department of the on Interior. It stood in a prominent location in front of Yosemite Fall.28 Workers also enlarged the blacksmith shop in 1910 and made minor repairs and improvements on nearly all park buildings used by the government.29 In 1911 Major Forsyth reported that the building used by the superintendent as a residence and office had been remodeled and enlarged, but remained unsuitable as living quarters. He recommended that the building serve only administrative purposes and that a separate residence be constructed for the superintendent. The army also constructed a new barn that year, in about the same location as the current government barn. It included a tack room, equipment warehouse, shoeing platform, and another small building.30

[28. Pavlik, “The Hutchings-Sovulewski Homesite,” 5-9.]

[29. Forsyth, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1910, 467.]

[30. Forsyth, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1911, 591. This barn became the center of park operations’ up into the 1920s. An arsonist burned the structure in 1972, destroying a variety of historical cavalry equipment.]

By 1913 Yosemite Village served as the focal point of settlement and activity in the valley. There visitors could find souvenirs and entertainment as well as groceries, rooms, and tourist information. At that time the village area north of the South Road, from west to east, contained a general store and post office, Boysen’s and Foley’s studios, the administration building, Best’s Studio, the dance and lecture pavilion, offices, the Cosmopolitan Bathhouse, Ivy Cottage, River Cottage, and the Sentinel Hotel. On the south side of South Road, west to east, stood the chapel, Pillsbury’s Studio, a butcher shop (later used for meat and beer storage by the Curry Company), John Degnan’s house, Degnan’s bakery, the Wells Fargo office, Rock Cottage, Oak Cottage, and Cedar Cottage. Scattered about the village were miscellaneous residences, tents, and outbuildings. Jorgensen’s Studio stood across the river and the Masonic31 Lodge west of the village behind the chapel. During the 1913 season, the old Lick House, the former boardinghouse near the stables, was repaired to accommodate civilian rangers Oliver R. Prien and Forrest Townsley.

[31. Allan Kress Fitzsimmons, “The Effect of the Automobile on the Cultural Elements of the Landscape of Yosemite Valley,” MA thesis, San Fernando Valley State College, 1969, 37. According to Laurence Degnan, the Masonic Lodge building originally served as a warehouse for Nelson Salter’s general store, which Salter had acquired from John Garibaldi, who had succeeded Mrs. Angelo Cavagnaro and had moved the store from its original location in the fork of the road north of the present chapel site. The warehouse probably had a post-1900 construction date. Laurence V. Degnan to Wayne W. Bryant, Jr., Park Naturalist, 30 November 1953, in Separates File, Y-4b, #24, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

In June of that year, Acting Superintendent Maj. William T. Littebrant recommended to the Secretary of the Interior that he send a board comprised of one landscape architect, one structural architect, and one civil engineer to the park to formulate a plan for its further improvement. He pointed out that so far improvements from year to year had depended upon the individuality and particular qualifications of each acting superintendent. Littebrant believed that park improvement should be a continuous process in accordance with a well-considered plan so that improvements one year became a continuation of those of the preceding year. As the system existed now, each superintendent had to renew the request for appropriations each year, making it uncertain as to whether work unfinished one year would be pursued the next. Also whenever a new superintendent arrived, he reformulated plans, and that practice did not lead to cohesive park planning.

Littebrant emphasized that the park was entering a new era, but that

The buildings in the Yosemite village are little more than a lot of shacks without architectural beauty, placed without plan or with careless, well designed absence of plan. . . . Any new constructions should be in harmony with the grandeur of the cliffs and the delicacy of the falls. The coloring of the buildings should not be in violent contrast with the grey of the rocks or the beauties of the pine and cedars. Concessioners should not be allowed to erect buildings designed by different architects without knowledge of the general plan- . . . The plan of the new village will call for artistic talent.32

[32. Major William T. Littebrant, Acting Superintendent, to Secretary of the Interior, 18 June 1913, in Central Files, RG 79, NA, 3. Basically, Littlebrant was requesting that buildings be constructed in the rustic style later developed and refined by the Park Service during the 1920s and 1930s.]

Littebrant suggested that in the future, stables, garages, and warehouses be placed on the north side of the Merced River and below the army post, far enough to permit expansion of the latter. Arguing that points of interest in the valley lay mostly above the army post and the Sentinel Hotel, Littebrant called for removing everything in that area that detracted from the beauty, grandeur, and harmony of the scene and rebuilding in a new location permanent structures following a selected design. Littebrant wisely discerned that the recommendations of a board of specialists such as he suggested would carry more weight with the Secretary of the Interior and with Congress than would those of the various acting superintendents.

This idea of Littebrant’s appealed to the Interior Department, and Assistant to the Secretary Adolph C. Miller duly conceived a program for the betterment of the park, which would include selection of the best locations for future roads, trails, and bridges; the clearing and trimming of wooded areas to provide attractive vistas; the proper location and arrangement of a new village in the valley; and general beautification. Although he attempted to follow through on this comprehensive general plan for development of the valley floor by appointing an advisory commission of talented and public-spirited citizens of standing in California, who agreed to provide their services with only reimbursement for expenses incurred, he ran up against a stumbling block.

Section 9 of the Sundry Civil Act of 4 March 1909 stated that no part of the public moneys or of Congressional appropriations would be used to pay expenses of any commission unless its creation was authorized by law. Unfortunately, no such authority could be secured at that time. The matter of an advisory board, therefore, lay in abeyance; in order to keep the project moving, however, Miller appointed Mark Daniels Landscape Engineer in 1914 and entrusted him with the task of working out a plan for the landscape treatment of Yosemite Valley.33

[33. Adolph C. Miller, Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, to Mark Daniels, 24 January 1914, and Miller to Leslie W. Symmes, 16 April 1914, in Central Files, RG 79, NA.]

During the 1915 season, conditions on the valley floor were studied with the intent of finding ways to relieve the congestion around the village as well as of designing a properly planned new village. Three plans were drawn regarding that subject, while studies continued on new hotels for the valley floor and Glacier Point and tentative plans took shape for twelve new carefully designed village buildings. The Department of the Interior also began to consider a new plan of concession operation in the park that would grant a concession to one large operator who would build a grand hotel on the valley floor, a smaller one at Glacier Point, and fifteen mountain inns in the high country. Under the terms of the proposed agreement, the concessioner would receive a permit of twenty years’ duration and share his net profits with the government.34

[34. Mark Daniels, “Report of the general superintendent and landscape engineer of national parks”; George V. Bell, Superintendent, “Report of the Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” 1 October 1915;] Gabriel Sovulewski, Park Supervisor, “Report of Park Supervisor”; and David A. Sherfey, Resident Engineer, “Report of the Resident Engineer,” 30 September 1915, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1915, 848-50, 853, 907-8, 912-14, 916, 918, 923, 925-26.]

In 1915 the acting superintendent provided a room in the administration building to house a collection of the different varieties of animals, birds, insects, woods, and flowers indigenous to Yosemite. Dr. Joseph Grinnell, director of the museum of vertebrate zoology of the University of California, supplied the exhibits, while the park ranger force helped secure and stuff birds and animals and assemble the wild flowers. The collection became of great interest not only to visitors, but also to the ranger department and park employees. This innovative exhibit became the cornerstone upon which the National Park Service constructed its later interpretive and museum programs for the park. The room housing these exhibits, the Bureau of Information, was established in the superintendent’s office in Yosemite Village during the 1915 season. In addition to providing information regarding road, trail, and camp conditions and scenic points of interest, it helped map trips, assign visitors to camps, handle correspondence related to tourist queries, collect auto fees, issue permits authorizing the entrance of autos over park roads, and keep statistical reports on travel.

3. Park General

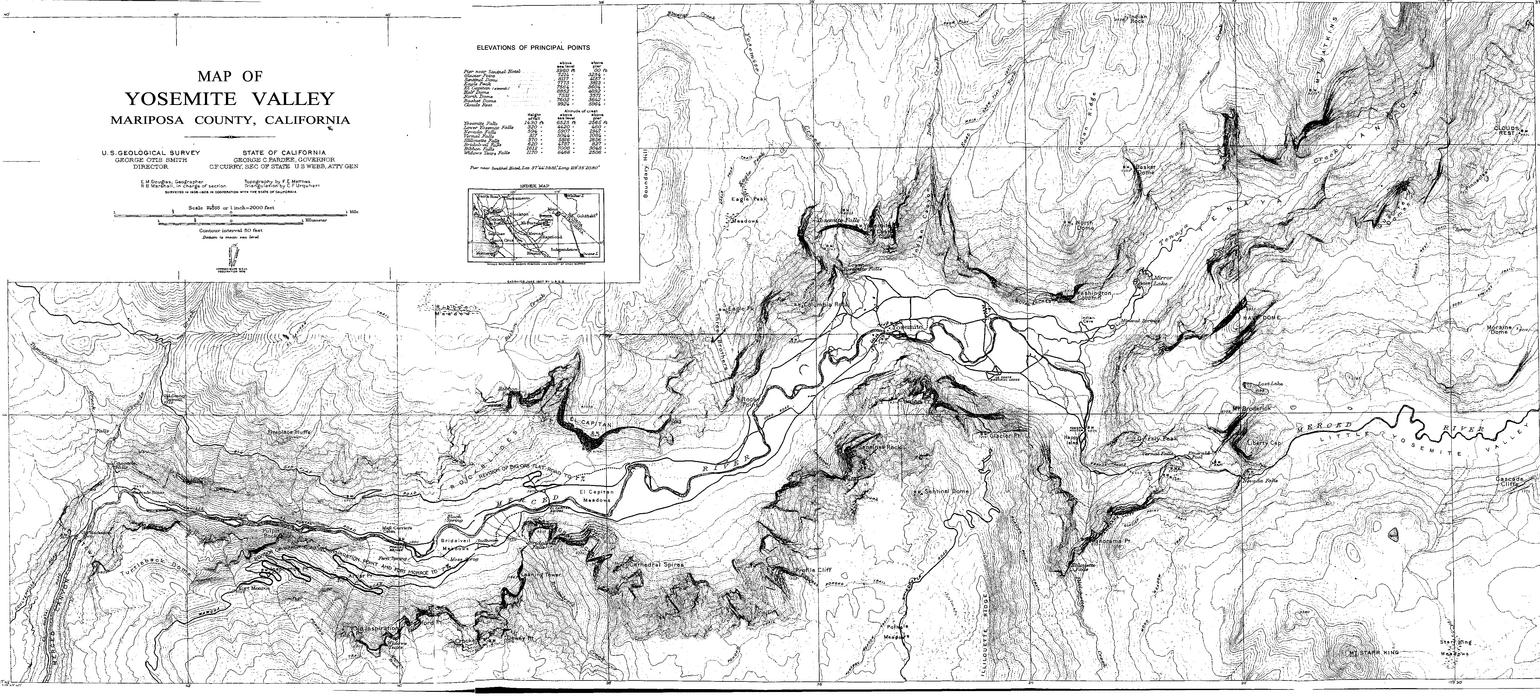

a) SchoolsAs mentioned in an earlier chapter, in 1897 valley Guardian Galen Clark had reported to the Yosemite Valley commissioners the need for a new schoolhouse and had suggested using the abandoned stage/telegraph office for that purpose. That building, constructed only a year earlier, stood on the road between the Sentinel Hotel and the Stoneman House, at the site of the present LeConte lodge. By 1907 it had evolved into a good public school attended by a dozen or more students, “including a few bright Indian children.”35 In 1909 the army

|

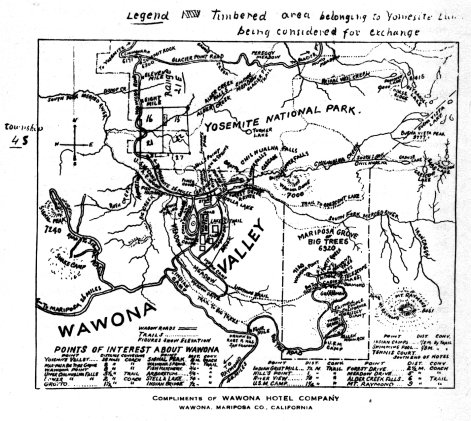

Illustration 58.

Map showing residence 5 (#2) built in 1912 by the U. S. Army near the present intersection of the shuttlebus and residence roads. The Park Service moved it in 1921 to the residential area where it is still used for employee housing. The schoolhouse (#3) moved to the north side of the Merced served as a residence after completion of a new school in 1918 until torn down in 1956. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

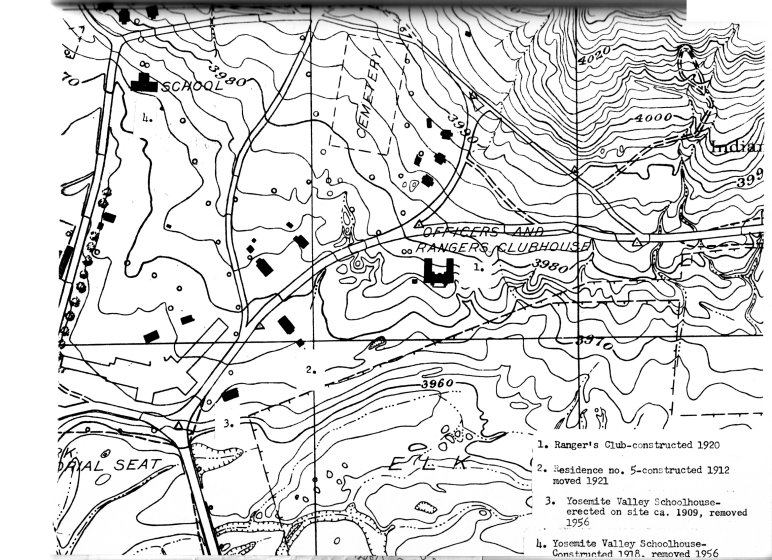

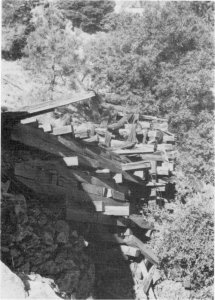

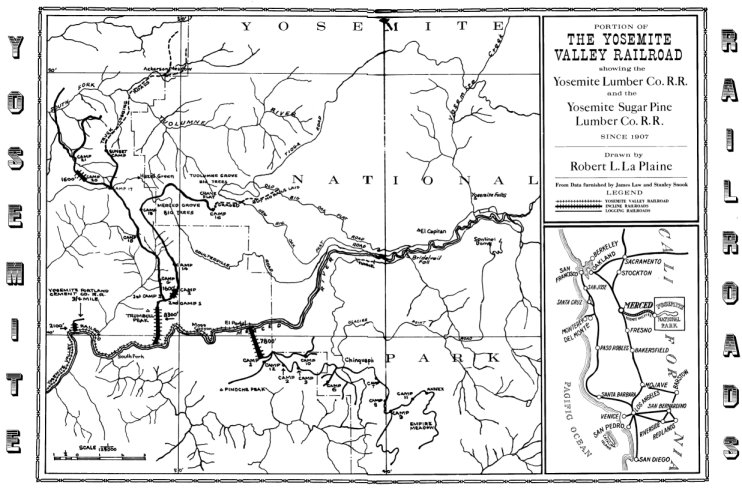

Illustration 59.

Crane Flat ranger patrol cabin, now at Pioneer Yosemite History Center, Wawona. Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

[35. Foley, Foley’s Yosemite Souvenir and Guide, 1907, 65-66.]

b) Powerhouse

In 1909 work began on fixing up the valley power plant, which needed to be replaced by one with a greater capacity. The iron pipe furnishing water to the plant ran through a tunnel of loose earth and stone, which had begun to cave in. During the 1910 season, a large appropriation enabled opening of a new trench for the pipe around the old tunnel. In 1911 laborers installed a new Pelton wheel in the power plant and a power-transmission system from Camp Ahwahnee to the rock quarry near Pohono Bridge. That enabled the water tank pumps and the rock crusher to operate during the summer by electric power. The two pumping stations in the valley and the pipeline along the El Portal road, necessary for the operation of the sprinkling wagons along that route, appeared to be operating successfully.36

[36. Forsyth, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1911, 591, 596.]

c) Miscellaneous

In 1910 park crews constructed cottages with barns and stables at Cascade Creek and Arch Rock for the use of road laborers and the drivers of road-sprinkling wagons.37 In 1911 a granite seat, a memorial to Galen Clark, was completed and placed about a quarter of a mile south of the foot of Yosemite Fall. In 1912 workers built rubble masonry wing dams along the Merced River where its banks suffered on heavy erosion.38

[38. Forsyth, “Report of Superintendent of Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1912, 670.]

[37. Forsyth, “Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Yosemite National Park,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1910, 467.]

d) Wood-Splitting Plant

During the 1914 season, a wood sawing and splitting plant was installed in Yosemite Valley to cut logs into firewood. Thicket clearing, an important part of work on the valley floor, protected growing trees from fires and destruction by rapid-growing dense undergrowth. The Interior Department sold the wood obtained in this manner to campers, concessioners, and department employees, and also used it in connection with sanitation projects and in public buildings. The plant consisted of a drag-saw, circular saw, wood splitter, and emery wheel, driven by an electric motor.39

[39. Sovulewski, “Report of the Park Supervisor,” and Sherfey, “Report of Resident Engineer,” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1914, 732, 735.]

e) Fire Lookouts and Patrol Cabins

In 1915 construction plans included two triangulation stations to be used as fire lookouts. Their locations on Mount Hoffmann and Sentinel Dome would make it possible to locate a fire within the district instantly and ascertain its exact location. (Ruins of the Mount Hoffmann lookout are still visible.) Other important additions to the park during the 1915 season consisted of three new patrol cabins—at Crane Flat, Hog Ranch, and the Merced Grove. The four-room log cabins with shake roofs measured thirty-two feet three inches by twenty-five feet and functioned as outpost checking stations. The checkpoints became necessary after the removal of U. S. Army troops, the entry of autos, and the employment of civilian rangers to protect the park. Tuolumne County’s purchase of the Big Oak Flat Road and the elimination of tolls increased the need for control stations on the park entrance road to regulate traffic, register cars, and collect fees. Each patrol cabin also had a twelve by twenty-foot shed stable of native poles and shakes.

The popularity of camping persisted in Yosemite Valley even after hotels and commercial camps came into existence. Originally there had been no restrictions on where camps could be struck or on site use in Yosemite Valley and horses could be grazed anywhere in the open meadows. The first campgrounds had been established by traditional use, primarily along the Merced River. Later, as stores and other services sprang up at the eastern end of the valley, the state commissioners tried to establish formal public campgrounds near them in order to free the rest of the valley floor for stock grazing and farming.

After the recession of the Yosemite Grant, Park Supervisor Sovulewski immediately became involved in a multitude of park administrative problems related to visitation. For instance, no sanitary or toilet facilities of any type existed in any of the campgrounds below Yosemite Village, so that camping in campgrounds nos. 1 to 5 west of the village was discouraged. Gradually those camps were entirely abandoned. The unfortunate conditions at certain campsites finally forced the superintendent to restrict camping to designated areas in the upper valley by the early 1900s.

After Benson left the park in October 1908 to relieve the commanding officer in Yellowstone National Park, Sovulewski took charge of the park and army property as Custodian. In May 1909 Col. William W. Forsyth took command of the park. He pondered the question of numbering campgrounds in the valley and decided to leave the old numbers and start with new ones to avoid confusing old-time park visitors. The original camps in Yosemite Valley consisted of:

Camp No. 1—EI Capitan Meadow. Early campers needed meadows for pasturing their horses and mules. Abandoned for sanitary reasons soon after 1906.

Camp No. 2—Bridalveil Meadow. Used almost exclusively by army troops when in the valley between 1890 and 1906. Abandoned for sanitary reasons soon after 1906.

Camp No. 3—west of Yosemite Village on the south side of the Merced River in the trees at the west end of the meadow near Galen Clark’s house. Abandoned for sanitary reasons soon after 1906.

Camp No. 4—Leidig Meadow, including portion of present Yosemite Lodge grounds. Retired from public use upon establishment of army headquarters in the valley. Abandoned for sanitary reasons also soon after 1906.

Camp No. 5—east of Yosemite Creek bridge, extending as far as the apple orchard and Hutchings’s cabin, including the area later occupied by the park supervisor’s home. Abandoned for sanitary reasons soon after 1906.

Camp No. 6—very old site. Later used by government and Yosemite Park and Curry Company employees. Located south of present park headquarters on north side of the Merced River.

Camp No. 7—still in original location along Merced River north of Camp Curry. Eventually divided by new road, creating two separate camps. East portion became No. 15.

Camp No. 8—located above Royal Arch Creek and included present Ahwahnee Hotel grounds. Erection of the hotel in 1926 forced its abandonment.

Camp No. 9—old site on Tenaya Creek adjacent to and including Royal Arch Meadow. Known as the “Organization Camp.”

Camp No. 10—near Iron Spring on Tenaya Creek, south of the old Mirror Lake Road. Contained only limited space, and camping was discouraged as demand for space in the area grew. Abandoned with change of road alignment to Mirror Lake in the administration of Superintendent Washington B. Lewis.

Camp No. 11 —originally intended to include the area now occupied by the Curry Company stables and extending eastward, but that area never functioned as a public campground. Number 11 was then assigned to its present site south of Camp 14 on the road to Happy Isles.

Camp No. 12—located across the Merced River from Camp No. 14, near Yosemite Park and Curry Company stables.

Camp No. 13—never existed for reasons of superstition.

Camp No. 14—still in original location, northeast of Camp Curry.

Camp No. 15—one-half of original Camp No. 7.